Developmental Disorders of Gastrointestinal Function

Colston F. McEvoy

Most gastrointestinal disease that presents in the neonatal period can be attributed to congenital anomalies. These defects in gut structure or function result from errors in fetal gastrointestinal development. Appreciation of the normal sequence of gastrointestinal development is key to understanding the abnormalities that can occur.

EMBRYOLOGY

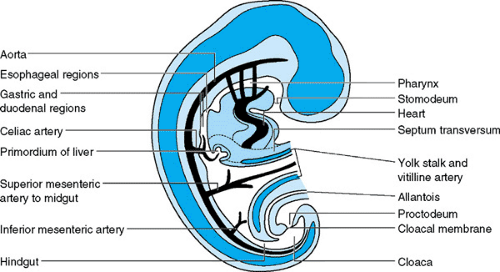

The primitive gut arises during the fourth week of gestation from the yolk sac as a tube extending from mouth to cloaca (Fig. 55.1). This tube consists of three parts, each supplied by a separate artery. Subsequent elongation and division of the primitive gut give rise to all the organs involved in digestion. The foregut develops into the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, liver, pancreas, and biliary system. These organs all receive their blood supply from the celiac axis. The midgut develops into the distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, right colon, and part of the transverse colon, which are supplied by the superior mesenteric artery. The hindgut develops into the distal colon, rectum, and superior anal canal, which are supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery. Epithelial cell formation and differentiation begin soon after organogenesis and parallel morphologic development of the digestive system. Digestive, absorptive, secretory, motility, hormonal, and immune functions develop throughout gestation as well as postnatally.

ESOPHAGEAL ANOMALIES

Esophageal Atresia

Esophageal atresia (EA), with or without an associated tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), is the most common esophageal malformation, occurring in 1 in 2,000 to 5,000 live births. The defect is thought to result from failed separation of the esophagus and trachea by a septum that forms by the fourth week of gestation.

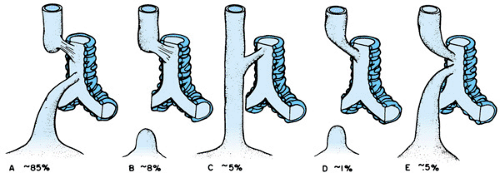

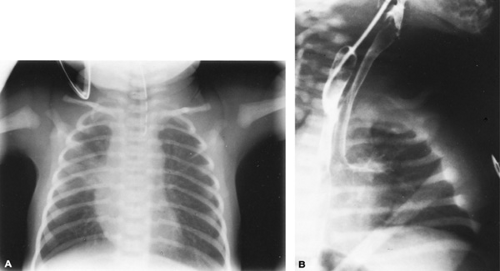

Five forms of EA with TEF occur (Fig. 55.2). The most common type is a proximal esophageal pouch and fistula connecting the trachea to the distal esophagus. Infants usually present at birth with copious oral secretions, respiratory distress, and aspiration. A history of maternal polyhydramnios is present in approximately 50%. Failure to pass an orogastric or nasogastric tube into the stomach is diagnostic. Roentgenography of the chest and abdomen shows the tube ending or coiled in the proximal pouch (Fig. 55.3A). The presence of gas in the stomach or small bowel is indicative of a coexisting TEF. These infants should be evaluated for other associated congenital anomalies. The origin of the VACTERL or VATER

association (vertebral anomalies, anorectal malformations, cardiac defects, TEFs, renal or radial anomalies, and limb malformations) is unknown. The rarer, H-type TEF, which connects an intact esophagus and trachea, usually presents later in infancy or childhood as feeding difficulties or chronic respiratory disease. This type of fistula requires special pull-back barium esophagraphy to make the diagnosis (Fig. 55.3B).

association (vertebral anomalies, anorectal malformations, cardiac defects, TEFs, renal or radial anomalies, and limb malformations) is unknown. The rarer, H-type TEF, which connects an intact esophagus and trachea, usually presents later in infancy or childhood as feeding difficulties or chronic respiratory disease. This type of fistula requires special pull-back barium esophagraphy to make the diagnosis (Fig. 55.3B).

Surgical treatment of EA and TEF includes identification and ligation of the fistula and, when possible, primary anastomosis of the esophageal remnants. If the gap is too long for end-to-end anastomosis, delayed repair after gradual elongation, colonic interposition, or bringing the stomach up may be performed. Children who have had EA repair often experience chronic problems with gastroesophageal reflux.

Laryngotracheal Clefts

Laryngotracheal clefts also result from incomplete separation of esophagus and trachea. The tracheoesophageal septum fails to complete its cranial growth, thus causing incomplete fusion of the cricoid cartilage and producing a cleft that extends by varying degrees into the larynx and trachea. The presenting symptoms in an infant depend on the extent of the cleft and include choking, aspiration during feeding, stridor, respiratory distress, recurrent pneumonia, and poor cry. Direct endoscopic visualization is the best way to make the diagnosis. Treatment ranges from no treatment in mild cases to intubation, tracheotomy, gastrostomy, or complicated definitive repair in severe cases.

Congenital Esophageal Stenosis and Webs

Congenital esophageal stenosis and webs are associated with EA and TEF. These may be milder variants of incomplete tracheal and esophageal separation or possible failure of recanalization at 10 weeks’ gestation. Webs are mucosal membranes that usually occur in the middle portion of the esophagus, typically the proximal end of the distal one-third. Stenosis is narrowing of the more distal esophagus because of tracheobronchial remnants. Neonates with complete webs present with symptoms of obstruction that are similar to those of EA. Stenosis or perforated webs usually present in infants as dysphasia, particularly with solids, as well as with vomiting, poor weight gain, and respiratory symptoms. A contrast study of the esophagus often identifies these lesions. Endoscopy may be helpful in identifying obscure webs and in ruling out strictures secondary to gastroesophageal reflux. A skilled endoscopist also may be able to resect the web. Surgical resection is necessary for complete webs and symptomatic stenoses. Dilation is usually not successful for true congenital esophageal stenosis, which may contain cartilage.

GASTRIC ANOMALIES

Microgastria

Microgastria is a rare malformation resulting from failure of the foregut to dilate. In addition, epithelial cells fail to differentiate, resulting in absent acid secretion. Association with a variety of other anomalies such as asplenia, malrotation, situs inversus, limb abnormalities, spinal deformities, and micrognathia is common. Clinically, infants present with vomiting, diarrhea, poor weight gain, or recurrent pneumonia. A small tubular stomach with incomplete rotation is identified on contrast study, often associated with a dilated esophagus. Optimizing nutrition through small frequent feedings or continuous tube feedings (gastric or jejunal) is the goal of treatment. When necessary, surgical procedures may be attempted to increase gastric capacity.

Gastric Antrum and Pyloric Atresias

Atresias of the gastric antrum or pylorus are rare. Although the embryologic etiology is unclear, segmental defects may result from discontinuation of the endodermal tube before 8 weeks’ gestation. An association of pyloric atresia with epidermolysis bullosa inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder has been described. Infants with gastric atresia present within the first day of life with vomiting, upper abdominal distention, and occasional gastric rupture. An abdominal plain film usually shows a large air-filled stomach with no distal gas. An upper gastrointestinal contrast study (UGI) is diagnostic. The absent pyloric muscle may be seen on ultrasound. Surgical therapy, with gastroduodenostomy or gastrojejunostomy, is performed after decompression and suctioning of the stomach with a nasogastric tube and correction of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities.

Antral Web

Antral webs are mucosal membranes that can partially or completely occlude the gastric lumen. Complete obstruction presents shortly after birth as nonbilious vomiting and can progress to catastrophic gastric rupture. These infants may be of low birth weight and have a history of polyhydramnios. Partial obstruction presents later in infancy or childhood as intermittent vomiting, failure to thrive, or postprandial pain or fullness. An incomplete or perforated web may be demonstrated by contrast study or endoscopy. Endoscopic or surgical incision is required if significant obstructive symptoms occur.

Gastric Volvulus

Gastric volvulus occurs when one part of the stomach rotates around another in either an organoaxial (longitudinal) or mesentericoaxial (transverse) direction. Abnormal fixation of the stomach or diaphragmatic abnormalities may contribute to the development of gastric volvulus in children. Associated asplenia and malrotation have been described in infantile cases. In an acute presentation, the symptoms are vomiting, retching, and abdominal pain. Chronic symptoms include postprandial pain, vomiting, and belching. UGI study shows the antrum lying high in the abdomen or in the chest in a mesentericoaxial volvulus. An organoaxial volvulus, seen in the majority of childhood cases, may be more difficult to identify. Surgical treatment to reduce the volvulus and to fix the stomach to the abdominal wall is required. This procedure should be done urgently in acute cases to prevent gastric ischemia and necrosis.

Pyloric Stenosis

Pyloric stenosis develops postnatally in the first weeks of life and results from hypertrophy of the pyloric muscle, which obstructs gastric outflow. The origin is unknown; however, the absence of nitric oxide synthase in the pyloric muscle has been implicated. Nitric oxide is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that mediates smooth muscle relaxation. The incidence of pyloric stenosis is 1 in 250 live births and is three to four times higher in boys than in girls. First-born infants and white infants are

affected more commonly. The mode of inheritance appears to be polygenic, with an increased risk in siblings and children.

affected more commonly. The mode of inheritance appears to be polygenic, with an increased risk in siblings and children.

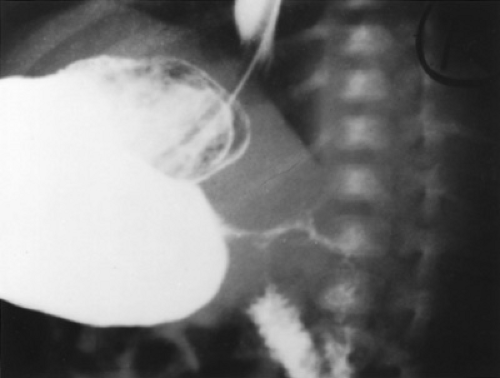

FIGURE 55.4. Pyloric stenosis. This radiograph is a lateral view from a barium study of the upper gastrointestinal tract performed on a vomiting infant. A thin stream of barium is seen exiting from the distended stomach through a markedly narrowed pyloric channel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|