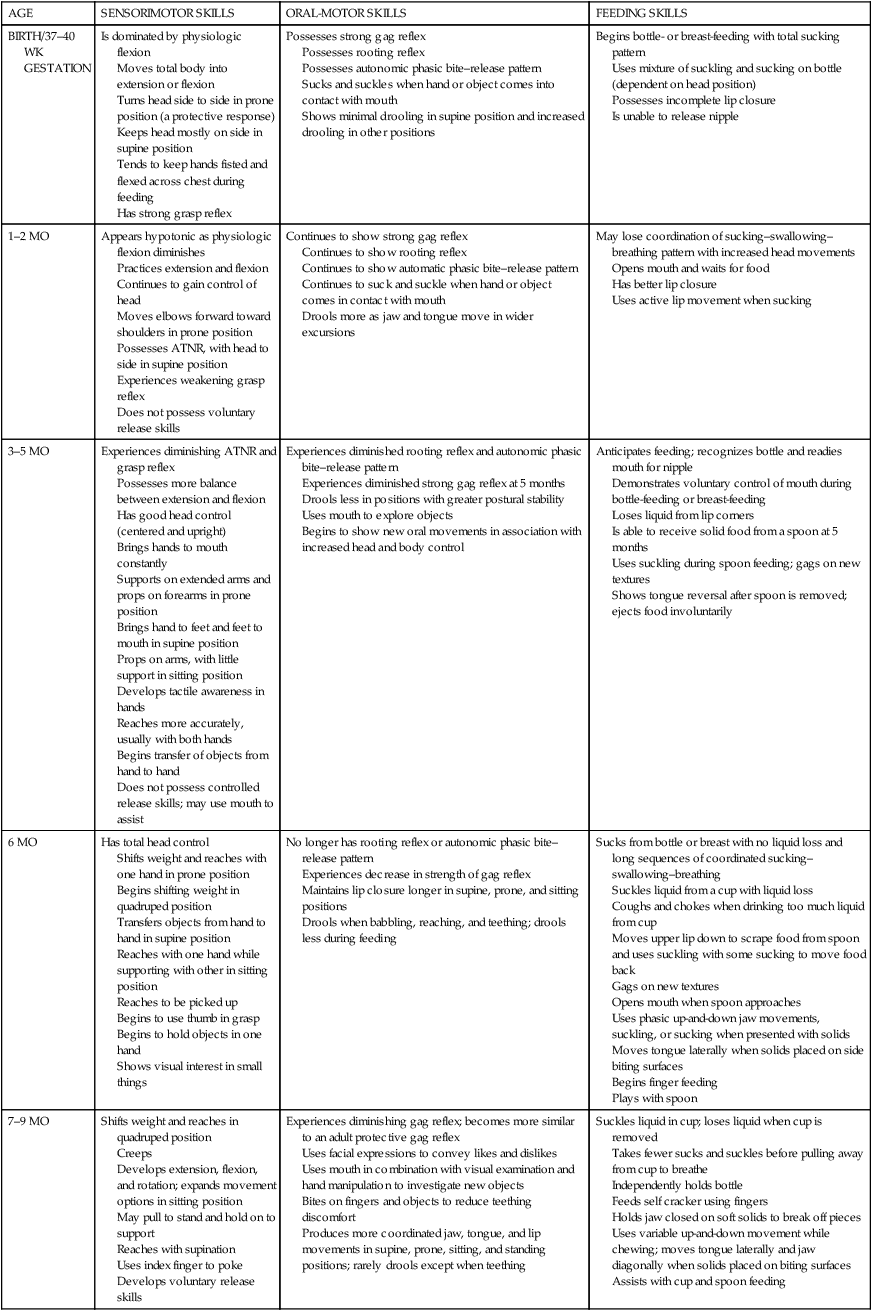

8 DIANNE KOONTZ LOWMAN, JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN and JEAN W. SOLOMON After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe the developmental sequence of oral motor control. • Identify the sequences of feeding and eating, dressing and undressing, and grooming and hygiene development. • Identify the types of food and utensils that are appropriate for infants and young children of different ages. • Identify the variables affecting a child’s development of self-care skills. • Describe age-appropriate home management activities. • Discuss care of others as it relates to humans and animals. • Describe developmentally appropriate activities considered as work or productive in the context of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework. • Explain the difference between formal and informal educational activities. • Identify age-appropriate vocational activities. • Define play and leisure skills. • Describe the progression of play skills. • Explain the relevance of play to occupational therapy practice. • Identify occupational therapy professionals who have made significant contributions to the study of play. Activities of daily living (ADLs) constitute one of the areas of occupation described in the American Occupational Therapy Association’s (AOTA’s) Occupational Therapy Practice Framework.2 The ADLs listed in Box 8-1 are the most basic tasks that children learn as they grow and mature.34 Basic self-care skills include feeding and eating, dressing and undressing, and grooming and hygiene.2 Because eating is a critical daily living skill essential to the child’s survival, growth, health, and well-being, it falls within the OT practitioner’s domain of concern.3 A child with sufficient eating skills is able to actively bring food to the mouth without assistance. A child who requires feeding must receive assistance in the activity of eating.3 Oral motor control relates to the child’s ability to use the lips, cheeks, jaw, tongue, and palate.36 Oral motor development refers to feeding, sound play, and oral exploration.28 Feeding is an oral motor skill, but some oral motor skills, such as oral motor awareness and exploration, do not involve food at all.14 The normal development of oral motor skills related to eating and feeding involves sucking from a nipple, coordinating the suck–swallow–breathe sequence, drinking from a cup, and munching and chewing solid foods.12,24,25 The maturation of these skills is closely tied to the physical maturation of the infant. The infant’s oral mechanisms differ anatomically from those of the adult; the oral cavity of the infant appears to be filled by the tongue. The small oral cavity, coupled with sucking fat pads that stabilize the infant’s cheeks, allows the infant to compress and suck on a nipple placed in the mouth. The limited mobility of the tongue results in the back and forth movement of the tongue known as suckling.24,28,29 As the size ratios in the mouth change with the infant’s growth, a more mature oral motor pattern emerges. By 4 to 6 months of age, the area inside the infant’s mouth increases as the jaw grows and the sucking fat pads decrease. These changes allow increased movement of the infant’s cheeks and lips. A “true sucking” pattern develops, as the infant’s tongue can move up and down as well as forward and backward. Increased control of the jaw, lips, cheeks, and tongue allows the infant to move food and liquid toward the back of the mouth and prepares the infant to accept and control strained baby food.28,30 Full-term infants are born with reflexes that allow them to locate the source of food, suck, and then swallow. The following describes these reflexes in relation to oral motor development.30 • Rooting reflex: When the infant’s cheeks or lips are stroked, he or she turns toward the stimulus. This reflex, which allows the infant to search for food, is maintained for a longer period in breast-fed infants. • Suck–swallow reflex: When the infant’s lips are touched, the mouth opens, and sucking movements begin. • Gag reflex: The gag reflex protects the infant from swallowing anything that may block the airway.28 At birth, the gag reflex is highly sensitive and elicited by stimulation to the back three fourths of the tongue. This reflex gradually moves to the back one fourth of the tongue as the infant matures and engages in oral play. • Phasic bite–release reflex: When the infant’s gums are stimulated, he or she responds with a rhythmic up-and-down movement of the jaw. This reflex forms the basis for munching and chewing. • Grasp reflex: When a finger is pressed into the infant’s palm, he or she grasps the finger. As the infant sucks, the grasp tightens, indicating a connection between sucking and the grasp reflex. Most of these early reflexive patterns begin to change or disappear between 4 and 6 months of age, when the cortex develops.28,30 Oral skills develop concurrently and are closely related to the overall development of sensorimotor skills. Table 8-1 presents a brief overview of the development of normal sensorimotor, oral motor, and feeding skills during the first 3 years of life. Feeding initially requires that the adult provide head support and head–trunk alignment to enable the infant to coordinate the suck–swallow–breathe sequence. The infant’s first suckling pattern predominates for the first 3 to 4 months of life.12 Beginning at 4 months, a “true sucking” pattern—an up-and-down tongue movement—develops as head and jaw stability appears. TABLE 8-1 Normal Development of Sensorimotor, Oral Motor, and Feeding Skills ATNR, asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. *From this point on, skills learned during the first 24 months are further refined. Adapted from Alexander R, Boehme R, Cupps B: Normal development of functional motor skills, Tucson, AR, 1993, Therapy Skill Builders; Bly L: Motor skills acquisition in the first year: An illustrated guide to normal development, Tucson, AR, 1994, Therapy Skill Builders; Case-Smith J, Humphrey R: Feeding and oral motor skills. In Case-Smith J, Allen AS, Pratt PN, editors: Occupational therapy for children, ed 2, St Louis, 1995, Mosby; Clark GF: Oral-motor and feeding issues. In Royeen CB, editor: AOTA self-study series: Classroom applications for school-based practice, Rockville, MD, 1993, American Occupational Therapy Association; Glass RP, Wolf LS: Feeding and oral-motor skills. In Case-Smith J, editor: Pediatric occupational therapy and early intervention, Boston, MA, 1993, Andover Medical; Lowman DK, Murphy SM: The educator’s guide to feeding children with disabilities, Baltimore, MD, 1999, Paul H Brookes; Lowman DK, Lane SJ: Children with feeding and nutritional problems. In Porr S, Rainville, EB, editors: Pediatric therapy: A systems approach, Philadelphia, 1999, FA Davis; Morris SE, Klein MD: Pre-feeding skills: A comprehensive resource for feeding development, Tucson, AR, 1987, Therapy Skill Builders. At 6 months, the infant has complete head control and more jaw stability, allowing for better control of tongue movements. This stability allows the infant to effectively suck from a bottle and take in soft food from a spoon.24 At 4 to 5 months, the infant demonstrates a reflexive phasic bite–release pattern when given a soft cracker. With practice, the rhythm progresses into a munching pattern, which involves an up-and-down jaw movement. The munching pattern is effective for eating baby food or other dissolvable foods.12,24 By 7 to 8 months, some diagonal jaw movements are added to the munching pattern. Infants use their fingers to eat soft crackers and cookies.12,24 Around 12 months, infants enjoy and prefer eating with their fingers. Rotary chewing movements and a well-graded bite are observed. At this time, many infants transition from drinking from a bottle to drinking from a cup. While learning to drink from a cup, the infant’s jaw initially continues to move in the up-and-down sucking pattern. In addition, the infant bites the rim of the cup to stabilize the jaw. By 15 months, the infant demonstrates some diagonal rotary movements of the tongue and jaw while chewing food. Between 15 and 18 months, the infant begins to independently eat with a spoon.12 By 24 months of age, the foundation has been established for all adult eating patterns.27 At age 2, children eat independently, consuming most meats and raw vegetables (Figure 8-1). Circular rotary chewing develops between the second and third year of life and allows toddlers to eat almost all adult foods.24,30 By 24 months, children can hold a spoon and bring it to the mouth with the wrist supinated into the palm-up position.28 At 30 to 36 months, children experiment with forks to stab at food. A variety of spoons are available for children learning to use utensils.21 The size of the spoon’s bowl should match the size of the child’s mouth. Children learning to use spoons typically use ones with shallow bowls; they have to work harder to eat food from spoons with deeper bowls. Child-size spoons and forks are easier for children to hold and manipulate, and bowls and plates with raised edges also make it easier for children to scoop the food.21,28 By 24 months, toddlers can also efficiently drink from cups. Children may begin drinking through straws between 2 and 3 years of age, especially if they have been exposed early to the use of straws. Given the variety of playful long, short, and decorated straws that are available on the market, children are happy to independently use their own straws.21 By 30 to 36 months, children try to serve themselves liquids and family-style servings of food.28

Development of occupations

Activities of daily living

Definition and rationale

Feeding and eating skills

Oral motor development

Infancy

AGE

SENSORIMOTOR SKILLS

ORAL-MOTOR SKILLS

FEEDING SKILLS

BIRTH/37–40 WK

GESTATION

Is dominated by physiologic flexion

Moves total body into extension or flexion

Turns head side to side in prone position (a protective response)

Keeps head mostly on side in supine position

Tends to keep hands fisted and flexed across chest during feeding

Has strong grasp reflex

Possesses strong gag reflex

Possesses rooting reflex

Possesses autonomic phasic bite–release pattern

Sucks and suckles when hand or object comes into contact with mouth

Shows minimal drooling in supine position and increased drooling in other positions

Begins bottle- or breast-feeding with total sucking pattern

Uses mixture of suckling and sucking on bottle (dependent on head position)

Possesses incomplete lip closure

Is unable to release nipple

1–2 MO

Appears hypotonic as physiologic flexion diminishes

Practices extension and flexion

Continues to gain control of head

Moves elbows forward toward shoulders in prone position

Possesses ATNR, with head to side in supine position

Experiences weakening grasp reflex

Does not possess voluntary release skills

Continues to show strong gag reflex

Continues to show rooting reflex

Continues to show automatic phasic bite–release pattern

Continues to suck and suckle when hand or object comes in contact with mouth

Drools more as jaw and tongue move in wider excursions

May lose coordination of sucking–swallowing–breathing pattern with increased head movements

Opens mouth and waits for food

Has better lip closure

Uses active lip movement when sucking

3–5 MO

Experiences diminishing ATNR and grasp reflex

Possesses more balance between extension and flexion

Has good head control (centered and upright)

Brings hands to mouth constantly

Supports on extended arms and props on forearms in prone position

Brings hand to feet and feet to mouth in supine position

Props on arms, with little support in sitting position

Develops tactile awareness in hands

Reaches more accurately, usually with both hands

Begins transfer of objects from hand to hand

Does not possess controlled release skills; may use mouth to assist

Experiences diminished rooting reflex and autonomic phasic bite–release pattern

Experiences diminished strong gag reflex at 5 months

Drools less in positions with greater postural stability

Uses mouth to explore objects

Begins to show new oral movements in association with increased head and body control

Anticipates feeding; recognizes bottle and readies mouth for nipple

Demonstrates voluntary control of mouth during bottle-feeding or breast-feeding

Loses liquid from lip corners

Is able to receive solid food from a spoon at 5 months

Uses suckling during spoon feeding; gags on new textures

Shows tongue reversal after spoon is removed; ejects food involuntarily

6 MO

Has total head control

Shifts weight and reaches with one hand in prone position

Begins shifting weight in quadruped position

Transfers objects from hand to hand in supine position

Reaches with one hand while supporting with other in sitting position

Reaches to be picked up

Begins to use thumb in grasp

Begins to hold objects in one hand

Shows visual interest in small things

No longer has rooting reflex or autonomic phasic bite–release pattern

Experiences decrease in strength of gag reflex

Maintains lip closure longer in supine, prone, and sitting positions

Drools when babbling, reaching, and teething; drools less during feeding

Sucks from bottle or breast with no liquid loss and long sequences of coordinated sucking–swallowing–breathing

Suckles liquid from a cup with liquid loss

Coughs and chokes when drinking too much liquid from cup

Moves upper lip down to scrape food from spoon and uses suckling with some sucking to move food back

Gags on new textures

Opens mouth when spoon approaches

Uses phasic up-and-down jaw movements, suckling, or sucking when presented with solids

Moves tongue laterally when solids placed on side biting surfaces

Begins finger feeding

Plays with spoon

7–9 MO

Shifts weight and reaches in quadruped position

Creeps

Develops extension, flexion, and rotation; expands movement options in sitting position

May pull to stand and hold on to support

Reaches with supination

Uses index finger to poke

Develops voluntary release skills

Experiences diminishing gag reflex; becomes more similar to an adult protective gag reflex

Uses facial expressions to convey likes and dislikes

Uses mouth in combination with visual examination and hand manipulation to investigate new objects

Bites on fingers and objects to reduce teething discomfort

Produces more coordinated jaw, tongue, and lip movements in supine, prone, sitting, and standing positions; rarely drools except when teething

Suckles liquid in cup; loses liquid when cup is removed

Takes fewer sucks and suckles before pulling away from cup to breathe

Independently holds bottle

Feeds self cracker using fingers

Holds jaw closed on soft solids to break off pieces

Uses variable up-and-down movement while chewing; moves tongue laterally and jaw diagonally when solids placed on biting surfaces

Assists with cup and spoon feeding

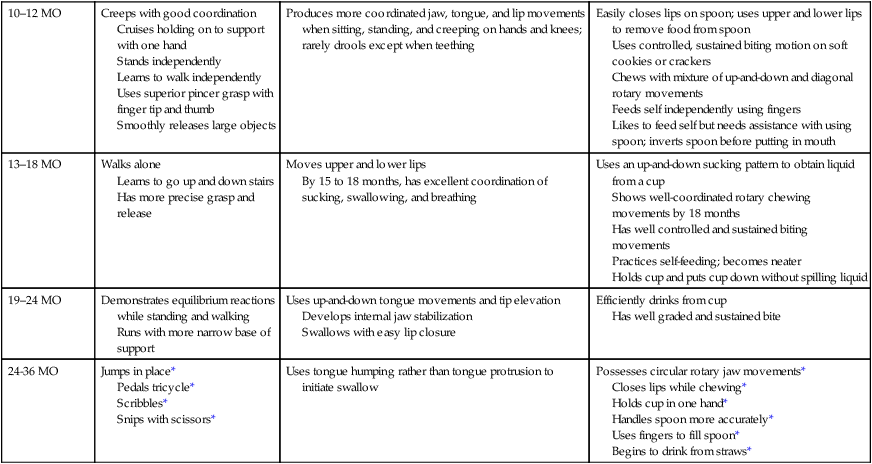

10–12 MO

Creeps with good coordination

Cruises holding on to support with one hand

Stands independently

Learns to walk independently

Uses superior pincer grasp with finger tip and thumb

Smoothly releases large objects

Produces more coordinated jaw, tongue, and lip movements when sitting, standing, and creeping on hands and knees; rarely drools except when teething

Easily closes lips on spoon; uses upper and lower lips to remove food from spoon

Uses controlled, sustained biting motion on soft cookies or crackers

Chews with mixture of up-and-down and diagonal rotary movements

Feeds self independently using fingers

Likes to feed self but needs assistance with using spoon; inverts spoon before putting in mouth

13–18 MO

Walks alone

Learns to go up and down stairs

Has more precise grasp and release

Moves upper and lower lips

By 15 to 18 months, has excellent coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing

Uses an up-and-down sucking pattern to obtain liquid from a cup

Shows well-coordinated rotary chewing movements by 18 months

Has well controlled and sustained biting movements

Practices self-feeding; becomes neater

Holds cup and puts cup down without spilling liquid

19–24 MO

Demonstrates equilibrium reactions while standing and walking

Runs with more narrow base of support

Uses up-and-down tongue movements and tip elevation

Develops internal jaw stabilization

Swallows with easy lip closure

Efficiently drinks from cup

Has well graded and sustained bite

24-36 MO

Jumps in place*

Pedals tricycle*

Scribbles*

Snips with scissors*

Uses tongue humping rather than tongue protrusion to initiate swallow

Possesses circular rotary jaw movements*

Closes lips while chewing*

Holds cup in one hand*

Handles spoon more accurately*

Uses fingers to fill spoon*

Begins to drink from straws*

Early childhood

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Development of occupations

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue