Sagittal sections showing the cephalocaudal folding of the embryo and the formation of the primitive gut

| Pharyngeal gut | Pharynx and related glands |

|---|---|

| Foregut | Oesophagus |

| Trachea and lung buds | |

| Stomach | |

| Duodenum proximal to the entrance of the bile duct | |

| Liver, biliary apparatus and pancreas | |

| Midgut | Duodenum distal to the opening of the bile duct |

| Small intestine | |

| Caecum and appendix | |

| Ascending colon and two-thirds of the transverse colon | |

| Hindgut | Distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon |

| Rectum and the superior part of the anal canal | |

| Epithelium of the urinary bladder and most of the urethra |

| Germ layer | Derived components |

|---|---|

| Endoderm | Epithelium of the digestive system |

| Parenchyma of the derivates of the gut | |

| Splanchnic mesoderm | Connective tissue |

| Muscular components | |

| Peritoneal components | |

| Ectoderm | Distal part of the anal canal |

| Portion of primitive gut | Arterial supply |

|---|---|

| Foregut | Branches of the coeliac trunk |

| Midgut | Branches of the superior mesenteric artery |

| Hindgut | Branches of the inferior mesenteric artery |

Foregut

Development of the oesophagus

In week 4, a respiratory diverticulum (lung bud) appears in the ventral wall of the foregut just beneath the pharyngeal gut. This diverticulum gradually gets partitioned from the dorsal part of the foregut by the tracheoesophageal septum. Thus, the foregut divides into a ventral respiratory primordium and a dorsal oesophagus. The oesophagus rapidly lengthens as the heart and lungs descend. The characteristics of the muscle coat of the oesophagus are outlined in Table 13.4.

| Portion of oesophagus | Muscle type | Nerve supply |

|---|---|---|

| Upper two-thirds | Striated | Vagus nerve |

| Lower third | Smooth | Splanchnic plexus |

Development of the stomach

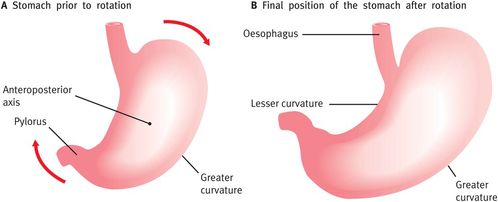

The stomach appears as a fusiform dilation of the foregut during week 4. It subsequently rotates around a longitudinal and an anteroposterior axis (Figure 13.2). The effects of this rotation have been summarised in Table 13.5.

Schematic representation of the rotation of the stomach on its anteroposterior axis

| Rotational change | Effects |

|---|---|

| 90°clockwise rotation around its longitudinal axis | The original left side now faces anterior and the original right side faces posterior |

| The left vagus nerve consequently innervates the anterior wall and the right innervates the posterior wall | |

| Anteroposterior rotation | The cephalic and caudal ends of the stomach no longer lie in the midline |

| The caudal or pyloric part moves to the right and upward and the cephalic or cardiac portion moves to the left and slightly downward |

During rotation, the original posterior wall (now on the left) grows faster than the anterior portion (now on the right), forming the greater and lesser curvatures respectively. The stomach thus assumes its final position, its axis running from above left to below right.

Mesenteries of the stomach

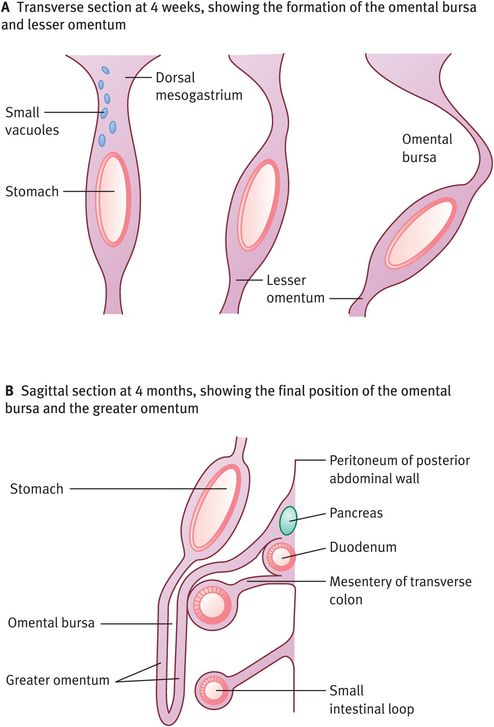

The stomach is suspended from the dorsal wall and ventral body wall by mesenteries, known as the dorsal and ventral mesogastrium respectively. Its rotation and dispro-portionate growth alter the position of these mesenteries.

The dorsal mesogastrium is pulled to the left, creating a space behind the stomach called the omental bursa (lesser peritoneal sac). It continues to grow down, forming a double-layered sac – the greater omentum (Figure 13.3). The two leaves of the greater omentum later fuse with each other and with the mesentery of the transverse colon.

The formation of the omental bursa and the greater omentum

The ventral mesogastrium is pulled to the right, forming the lesser omentum (which passes from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach) and the falciform ligament (which extends from the liver to the ventral abdominal wall). On its way from the umbilical cord to the liver, the umbilical vein passes in the free border of the falciform ligament (Figure 13.4).

The effect of rotation of the stomach on the position of the mesenteries

Development of the duodenum

The duodenum also develops early in week 4. Since it develops from both the terminal part of the foregut and the proximal part of the midgut, it is supplied by branches of both the coeliac artery and the superior mesenteric artery. The junction of these two parts is just distal to the origin of the bile duct. As the stomach rotates, the duodenum takes on the form of a C-shaped loop, rotates to the right and becomes retroperitoneal. The region of the duodenal cap, however, retains its mesentery and remains intraperitoneal. During weeks 5–6, proliferation of epithelial cells results in temporary obliteration of the lumen of the duodenum, but this is recanalised by the end of the embryonic period.

Development of the liver and biliary apparatus

Rapidly proliferating cells at the distal end of the foregut result in the formation of a ventral outgrowth early in week 4. This is the hepatic diverticulum (liver bud), which then penetrates the septum transversum and goes on to form the liver and the biliary apparatus (Figure 13.5). The bile duct is formed when the connection between the hepatic diverticulum and the foregut (duodenum) subsequently narrows. The bile duct develops a small ventral outgrowth that then goes on to form the gallbladder and the cystic duct.

Sagittal sections showing the penetration of the septum transversum by the rapidly proliferating cells of the hepatic diverticulum (liver bud) and the subsequent development of the liver and the biliary apparatus

The surface mesoderm of the liver differentiates into visceral peritoneum, except on the cranial surface, where the liver remains in contact with the rest of the original septum transversum. This portion of the septum, which comprises densely packed mesoderm, forms the central tendon of the diaphragm, and the surface of the liver that is in contact with the future diaphragm forms the bare area of the liver. This area is never covered by peritoneum. The liver grows rapidly and, by week 9, accounts for approximately 10% of the body weight. Initially, the right and left lobes are approximately the same size, but the right lobe soon becomes larger.

Haematopoiesis begins during week 6, giving the liver a bright red appearance. Bile formation by hepatic cells begins during week 12. When the cystic duct joins the hepatic duct to form the bile duct, bile enters the gastro-intestinal tract and its contents take on a dark green colour. This entrance of the bile duct is initially anterior but, because of positional changes of the duodenum, it moves posteriorly and finally comes to lie behind the duodenum. The origin of various hepatic cells is outlined in Table 13.6.

| Origin | Cell type |

|---|---|

| Mesoderm of the septum transversum | Haematopoetic cells |

| Kupffer cells | |

| Connective tissue cells | |

| Liver cords | Parenchyma (liver cells) lining the biliary ducts |

| Intermingling of epithelial liver cords with vitelline and umbilical veins | Hepatic sinusoids |

Development of the pancreas

Two separate buds, the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds, originate from the endodermal lining of the duodenum and grow rapidly between the layers of the dorsal mesentery. These go on to form the pancreas (Figure 13.6). The larger dorsal pancreatic bud appears first and develops cranial to the ventral pancreatic bud, which in turn develops near the entry of the bile duct into the duodenum. Rotation of the duodenum causes the ventral bud to move dorsally and finally to lie immediately below and behind the dorsal bud. Subsequently, the parenchyma and the duct systems of the two buds fuse and the main pancreatic duct enters the duodenum along with the bile duct at the major papilla. The accessory pancreatic duct (when present) enters the duodenum at the minor papilla. Figure 13.6 and Table 13.7 provide more details.

Development of the pancreas

Partitioning of the cloaca

| Origin | Final structure |

|---|---|

| Ventral pancreatic bud | Uncinate process and inferior part of head of pancreas |

| Dorsal pancreatic bud | Entire pancreas except for the above |

| Ventral pancreatic duct and the distal part of dorsal pancreatic duct | Main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung) |

| Proximal part of dorsal pancreatic duct (if and when it persists) | Accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree