Dermatologic Diseases

Todd E. Holmes

Paul A. Krusinski

BIRTHMARKS

Birthmarks comprise a wide spectrum of common and uncommon congenital disorders, the recognition of which is crucial for predicting the natural course and potential for associated abnormalities. Table 68.1 lists the incidence of common birthmarks.

Pigmented Lesions

Melanocytes are melanin-producing cells that originate in the neural crest and migrate in utero to the skin, mucous membranes, eyes, inner ear, and central nervous system (CNS). Tumors of melanocytes in the skin are composed of one of three types of cells: nevus cells, epidermal melanocytes, and dermal melanocytes (Box 68.1). All melanocytic tumors, except freckles, may be present at birth. Freckles are acquired later in childhood. Melanocytic nevi are further classified as junctional, intradermal, or compound when the location of nevus cells is within the epidermis, the dermis, or both, respectively.

Congenital Melanocytic Nevus

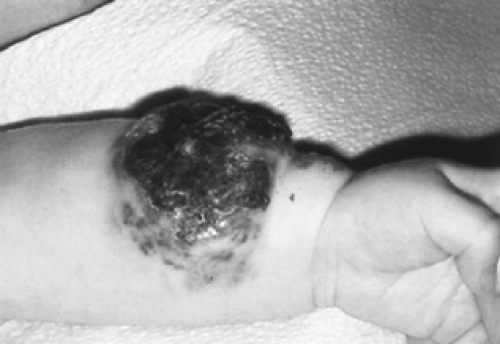

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) occur in 1% to 6% of all newborns and are classified according to the size they attain or are predicted to attain in adulthood. Nevi that are less than 1.5 cm in diameter are classified as small, nevi between 1.5 and 19.9 cm in diameter are classified as medium, and nevi that are 20 cm or greater in diameter are classified as large. The very large CMN involving a major portion of the body are often referred to as “giant” or “bathing trunk” nevi. CMN typically present as sharply demarcated, often multicolored and hairy, dark brown patches. In some CMN, especially the larger ones, the overlying skin can be thickened and verrucous, and satellite lesions may be present. CMN are significant because of their increased risk for development of malignant melanoma. The risk for developing melanoma increases with the size of the nevus. The lifetime risk for developing melanoma in patients with CMN less than 20 cm in diameter is estimated to be between 0% and 4.9% with most melanomas developing at or after puberty, whereas the lifetime risk of developing melanoma in patients with CMN greater than 20 cm is estimated to be between 4.5% and 10% with most melanomas arising before puberty. If prophylactic removal is decided, it should be performed early in life for large CMN and any time up to puberty for small and medium CMN. Features that suggest development of melanoma in a CMN include change in color, irregular or scalloped border, change in size or thickness, variation in color within the lesion, bleeding, or ulceration. CMN may have irregular borders and variation in color and thickness from the outset, making it difficult to follow these lesions for early malignant changes (Fig. 68.1). All CMN with atypical or suspicious features should be excised regardless of size.

TABLE 68.1. INCIDENCE OF BIRTHMARKS IN NEONATES | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients with large CMN are also at risk for neurocutaneous melanocytosis. The highest risk for melanoma or neurocutaneous melanocytosis is seen in patients with large CMN in a posterior axial location, especially when associated with satellite smaller CMN. Neurocutaneous melanosis can result in seizures, hydrocephalus, or focal neurologic defects. A risk exists of developing a primary malignant melanoma in the leptomeningeal lesions as well as the cutaneous CMN.

Dermal Melanocytosis

Often referred to as Mongolian spots, dermal melanocytosis (DM) is characterized by blue-gray, poorly defined patches

that are most commonly seen overlying the sacral region of the newborn. It is the most commonly encountered congenital pigmented lesion; however, there are marked racial differences in prevalence. It is seen in 95% of black, 81% of Asian, 46% to 70% of Hispanic, and 10% of white infants. The lesions are due to the delayed disappearance of dermal melanocytes. To help avoid possible confusion with bruising, DM should always be documented when detected on physical examination. DM is benign and usually disappears during the first or second year of life, but may persist in dark-skinned individuals.

that are most commonly seen overlying the sacral region of the newborn. It is the most commonly encountered congenital pigmented lesion; however, there are marked racial differences in prevalence. It is seen in 95% of black, 81% of Asian, 46% to 70% of Hispanic, and 10% of white infants. The lesions are due to the delayed disappearance of dermal melanocytes. To help avoid possible confusion with bruising, DM should always be documented when detected on physical examination. DM is benign and usually disappears during the first or second year of life, but may persist in dark-skinned individuals.

BOX 68.1 Benign Melanocytic Tumors of the Skin

Nevus cells

Melanocytic/nevocellular nevus

Epidermal melanocytes

Freckle (ephelis)

Lentigo

Café au lait spot

Dermal melanocytes

Mongolian spot

Blue nevus

Nevus of Ota

Nevus of Ito

FIGURE 68.1. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus with atypical features, including a scalloped border, irregular pigmentation, and variable thickness. See Color Figure 68.1 in color section. |

Blue Nevus

Blue nevi are uncommon benign tumors composed of dermal melanocytes that may be present at birth. The common blue nevus and the cellular blue nevus cannot be distinguished clinically but differ histologically. Blue nevi are well-circumscribed, slate blue or bluish black papules or nodules with a predilection for the buttocks, face, or dorsum of the hands and feet. Common blue nevi are usually less than 15 mm in diameter and are not a risk for the development of malignant melanoma. Cellular blue nevi are often larger and may rarely undergo malignant transformation into malignant melanoma.

Café au Lait Spot

Café au lait spots (CALSs) are well-circumscribed, homogenously pigmented, light brown macules that range from 1.5 to 15 cm in diameter. They are frequently present at birth, are almost always present by 1 year of age, and may increase in number during early childhood. CALSs are seen in approximately 2% of all newborn infants and up to 25% of the normal adult population. They are more common in darker-pigmented races. The vast majority of patients with CALSs have one or two lesions and have no associated abnormalities. However, the presence of six or more with a diameter of greater than 0.5 cm before puberty and 1.5 cm after puberty is highly suggestive, but not diagnostic, of neurofibromatosis. CALSs are also seen in other disorders, including tuberous sclerosis, McCune Albright syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, and Bloom syndrome.

Mastocytosis

Mastocytosis is an uncommon disorder characterized by the abnormal accumulation of mast cells in tissues. Mast cell disease encompasses a spectrum from isolated cutaneous involvement to systemic disease (Table 68.2). The cause for the increase in mast cell numbers is not completely understood. However, mutations of c-kit, the receptor for mast cell growth factor, on mast cells have been demonstrated. Cutaneous lesions appear as red-brown to yellow-brown macules, papules, or nodules that range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Characteristically, the skin lesions will urticate with rubbing (Darier sign) because of mast cell degranulation and histamine release resulting in increased vascular permeability, edema, and wheal formation. If the edema is marked, blistering may occur. Mastocytomas are present at birth or develop shortly thereafter and appear as reddish-brown plaques or nodules. Single lesions are the rule, although occasionally two or three are present, typically involving the distal extremities, particularly the wrist. Most isolated mastocytomas resolve spontaneously after several years. Generalized cutaneous mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) is characterized by the appearance of multiple red-brown macules, papules, and plaques (Fig. 68.2). The majority of cases occur before puberty, with about half presenting before 9 months of age. Most affected children have significant clearing or complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions by early adulthood. Systemic symptoms may occur because of release of histamine and other mediators from cutaneous lesions and include pruritus, flushing, hypotension, tachycardia, and, less often, diarrhea, dyspnea, and syncope. Systemic mastocytosis with mast cell infiltration of bone, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, skin, and gastrointestinal tract is rare in children.

TABLE 68.2. CLASSIFICATION OF MASTOCYTOSIS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FIGURE 68.2. Multiple pinkish brown papules and nodules of generalized cutaneous mastocytosis. See Color Figure 68.2 in color section. |

Epidermal Nevus

Epidermal nevi are benign tumors in which the epidermis is hyperplastic. A variety of names have been given to this lesion, including linear epidermal nevus, nevus unius lateris, ichthyosis hystrix, and systematized epidermal nevus. Most epidermal nevi are present at birth and may become more extensive with age. The lesions are tan, brown, or black verrucous growths arranged in a linear, asymmetric fashion and are more often unilateral than bilateral. The diagnosis of epidermal nevus syndrome is made when epidermal nevi are seen in association with central nervous system, ocular, musculoskeletal, and other organ abnormalities. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi (ILVEN) are distinguished from linear epidermal nevi clinically by the presence of pruritus and erythema and histologically by the presence of inflammation and parakeratosis. They are usually present at birth and occur mainly on the extremities in girls.

Nevus Sebaceous

Sebaceous nevi are benign hamartomas of sebaceous and apocrine glands that present at birth on the head or neck. They are well-circumscribed, often linear, yellow-orange, smooth, hairless, verrucous plaques (Fig. 68.3). At puberty, enlargement occurs as the sebaceous glands become active under androgenic influence. Large sebaceous nevi may be associated with congenital skeletal defects and CNS disease, including mental retardation and seizures, much like those seen in the epidermal nevus syndrome. Small, isolated lesions of sebaceous nevi are not associated with other defects. During adulthood, sebaceous nevi may be complicated by secondary tumor development. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastomas are the most common tumors to arise from sebaceous nevi and occur in approximately 10% of the cases. Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) were previously believed to be the most common tumors arising from sebaceous nevi. However, retrospective studies have shown that the majority of these cases were actually trichoblastomas. Because most tumors occur in adults older than age 40 and the incidence of BCC is much lower than once believed, prophylactic surgery is of unclear benefit and clinical follow-up is probably sufficient.

FIGURE 68.3. Linear nevus sebaceous on the neck and posterior ear with typical sharply demarcated, waxy, yellow-orange, pebbly appearance. See Color Figure 68.3 in color section. |

Hypopigmented Lesions

Ash Leaf Spot

Ash leaf spots are present in 85% of individuals with tuberous sclerosis and are the only cutaneous manifestation of tuberous sclerosis present at birth or in early infancy. Clinically they are characterized by hypopigmented, leaf-shaped macules with smooth or jagged borders. Linear and confetti-like hypopigmented macules may also be seen. Other skin lesions characteristic of this disorder develop later in childhood or in early adolescence, including adenoma sebaceum (multiple facial angiofibromas), periungual fibromas (Koenen’s tumors), shagreen patches, and CALSs. Ash leaf spots persist, and affected individuals may continue to develop new lesions during childhood. Wood’s light examination aids in the detection of ash leaf spots in fair-skinned infants.

Nevus Depigmentosus

Nevus depigmentosus (ND), also called achromic nevus, is a congenital hypopigmented macule or patch that is stable in its relative size and shape throughout life. ND should be distinguished from vitiligo. ND is present at birth, whereas vitiligo usually presents later in childhood or adulthood. Lesions of ND are slightly off-white when compared to the milky white lesions of vitiligo. Vitiligo is caused by the complete loss of melanocytes and melanosomes in the skin, whereas the lesional skin of ND is thought to have abnormal melanosomes with a normal complement of melanocytes. ND is usually not associated with other defects.

Piebaldism

Piebaldism is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the c-kit gene, in which depigmented patches of skin are present at birth. Characteristic features are a white forelock or hypopigmented tuft of hair in the frontal region and the presence of normally pigmented islands of skin within the leukoderma. Some affected individuals have been reported to have cerebellar ataxia, neurosensory deafness, or mental retardation. A white forelock, leukoderma, heterochromic irides and fundi, hypertelorism, congenital deafness, premature graying of hair, confluence of the medial eyebrows, and a broad nasal root are manifestations of Waardenburg syndrome. Also autosomal dominant, there are several genetic variants of this disorder that are caused by mutations of the PAX3, MITF, or ENDRB genes.

Hypomelanosis of Ito

Hypomelanosis of Ito (incontinentia pigmenti achromians) is a rare disorder of irregular, linear, and whorled hypopigmentation on the trunk and extremities. Approximately three-fourths of affected individuals will have associated abnormalities of the CNS, eyes, teeth, nails, hair, musculoskeletal system, or internal organs. In most cases, the pigmentary changes are present at birth or within the first year of life and may become more extensive.

Nevus Anemicus

Nevus anemicus is a congenital developmental anomaly that is characterized by hypopigmented macules of varying size and shape. The involved area is lighter than the normal skin, not because a loss of pigment occurs, but because blood vessels are constricted, producing a permanent blanching of the area. This blanching is a functional rather than a structural abnormality, presumed to be caused by local increased sensitivity to catecholamines. The color difference between the nevus and the normal skin can be accentuated by brisk rubbing; the normal skin becomes red, whereas the nevus does not. A nevus anemicus is not generally associated with other defects and does not change with age.

Vascular Lesions

Normal Variants

Cutis Marmorata

Cutis marmorata is the normal, reticulated, cyanotic mottling of the skin that is a physiologic response to chilling. This change is not normal if it persists after the infant is warmed. Persistent mottling or livedo reticularis implies an obstruction to blood flow such as hyperviscosity or vasculitis.

Harlequin Color Change

The harlequin color change is a benign phenomenon seen in up to 9% of premature infants and is thought to be caused by immature vasomotor control or transient hypothalamic hypoxia with vasospasm. When the infant lies on his or her side, the lower half of the body becomes reddened and the upper half blanches. An episode may last for several seconds or minutes and resolves spontaneously when the infant is placed in the supine position.

Congenital Vascular Abnormalities

Congenital vascular abnormalities can be classified as vascular tumors or vascular malformations (Box 68.2). Vascular tumors are benign neoplasms of vascular endothelium and are characterized by cellular proliferation. Vascular malformations, in contrast, are structural anomalies derived from arteries, veins, or lymphatics and do not have a proliferative phase. These malformations remain stable, with the growth of the lesion correlating with the growth of the child.

Vascular Tumors

Infantile Hemangiomas

Infantile hemangiomas and hemangiomas of infancy are terms now used to describe a group of vascular tumors that have historically been recognized as strawberry hemangiomas or capillary hemangiomas. The most common benign tumor of infancy, infantile hemangiomas occur in up to 2.6% of all neonates and up to 10% of Caucasian children. They are especially common in premature infants, especially those weighing less than 1,500 g, and are two to five times more frequent in females than in males. About half of infantile hemangiomas are present at birth, with the remainder becoming evident within the first month of life. Infantile hemangiomas may occur anywhere on the skin and mucosal surfaces. Their location in the skin may be superficial, deep, or mixed, which results in a variety of clinical appearances. When fully developed, superficial hemangiomas (50% to 60%) are bright red with a finely lobulated surface. Deep hemangiomas (15%) present as blue-purple masses with minimal to no overlying skin changes. Mixed superficial and deep hemangiomas (25% to 35%) have features of both (Fig. 68.4). If not present at birth, infantile hemangiomas may be preceded by a telangiectatic macule surrounded by an area of pallor, a pink macule, or a bruise-like patch. These early lesions are subtle and are often mistaken for port wine stains (PWSs).

BOX 68.2 Congenital Vascular Abnormalities

Vascular tumors

Infantile hemangioma

Congenital hemangioma

Tufted hemangioma

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

Pyogenic granuloma

Vascular malformations

Capillary malformations

Lymphatic malformations

Venous malformations

Arteriovenous malformation

Parents frequently become alarmed when a hemangioma begins to grow, particularly if it becomes eroded or bleeds. The natural history of these lesions must be stressed, because more than 90% resolve spontaneously. Hemangiomas grow rapidly during the first 6 months of life, with most reaching their maximal growth by the time the infant is 18 months old. A general rule is that 30% resolve by 3 years of age, 50% by 5 years, 70% by 7 years, and 90% by 9 years. While most hemangiomas are asymptomatic and can be managed by close observation, up to 20% may have associated complications. Indications for aggressive treatment include compromise of a vital function (sight, respiration, or nutrition), high-output congestive heart failure, consumptive coagulopathy, and significant ulceration or deformity. A course of systemic corticosteroids is the treatment of choice, with a starting dosage of 2 to

3 mg/kg/day followed by a tapering course over 2 to 4 months. To avoid potential side effects associated with systemic therapy, corticosteroids may be used both intralesionally and topically in selected cases. Pulse dye laser (PDL) surgery is accepted as an effective treatment of ulceration and residual erythema or telangiectasia. PDL treatment of proliferating hemangiomas, however, is more controversial. Interferon alfa is effective, but a significant risk of spastic diplegia has limited its use to those infants with life-threatening or severely function-threatening hemangiomas.

3 mg/kg/day followed by a tapering course over 2 to 4 months. To avoid potential side effects associated with systemic therapy, corticosteroids may be used both intralesionally and topically in selected cases. Pulse dye laser (PDL) surgery is accepted as an effective treatment of ulceration and residual erythema or telangiectasia. PDL treatment of proliferating hemangiomas, however, is more controversial. Interferon alfa is effective, but a significant risk of spastic diplegia has limited its use to those infants with life-threatening or severely function-threatening hemangiomas.

FIGURE 68.4. Mixed superficial and deep infantile hemangioma on the left forearm with ulceration and crusting. The superficial component is bright red; the deep component is blue. See Color Figure 68.4 in color section. |

Congenital Hemangiomas

Rarely, infants can present with a fully developed hemangioma at birth. This subset of hemangiomas is distinct from infantile hemangiomas and is characterized by intrauterine growth, little to no growth in the postnatal period, and rapid involution within the first year of life.

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, in which platelets are trapped and coagulation factors are consumed locally within a vascular lesion, is a complication of tufted angiomas and kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas. This syndrome is manifested by an enlarging vascular lesion with surrounding ecchymoses and may develop into a full-blown disseminated intravascular coagulation-like picture with thrombocytopenia and a hemorrhagic diathesis.

Diffuse Neonatal Hemangiomatosis

Multiple lesions are seen in approximately 15% of infants with hemangiomas and are an indication of possible visceral involvement. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis is a term used to describe infants with multiple visceral and cutaneous hemangiomas. Benign neonatal hemangiomatosis is used to describe infants with cutaneous involvement only. The CNS, liver, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract are the most common sites of involvement in diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis. Affected infants are noted at birth to have small, red to bluish black, papular hemangiomas 0.2 to 2.5 cm in diameter, and they may develop hundreds of similar lesions in infancy (Fig. 68.5). Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis is a life-threatening condition with reported mortality rates ranging between 29% and 80%. Treatment with systemic corticosteroids may result in involution of the cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas. If the infants survive, the hemangiomas tend to regress with time, much like typical hemangiomas of infancy.

FIGURE 68.5. Newborn with multiple 1- to 4-mm, firm, red, papular cutaneous hemangiomas of the diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis syndrome. See Color Figure 68.5 in color section. |

PHACES Syndrome

Large hemangiomas on the face and neck are seen more frequently in female children (7:1) and are associated with other congenital abnormalities. The acronym PHACES is used to describe these anomalies (posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, eye abnormalities, and sternal defects and supraumbilical raphe).

Vascular Malformations

Nevus Flammeus

The most common of all birthmarks, the nevus flammeus is a pink macule found over the glabella, eyelids, nasolabial folds, or nape of the neck. These capillary malformations are often referred to as “salmon patches” or “angel kisses” when they occur on the face and “stork bites” when they occur on the nape of the neck. The facial lesions tend to fade or disappear during childhood, whereas those that occur in the nape area may not.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree