Uniapical deformity versus multiapical deformity

Coronal, sagittal, and rotational parameters of each deformity

Soft-tissue envelope/vascularity of bone

Patient/caretaker perception of problem

Patient comorbidities

Prior treatment successes and challenges

After a problem list has been developed, the anatomy and biology of the underlying deformity must be considered. In particular the surgeon should decide whether the location of the deformity is more amenable to acute or gradual correction based on the anatomy of the neurovascular structures and postoperative or posttraumatic scarring. Are the physes open, leaving the option of growth modulation to correct the deformity? The presence of active or prior infection is another important factor to be considered, as are factors such as the presence of a pseudarthrosis.

When considering the problem list in conjunction with the anatomy and biology of the problem, the surgeon should be able to outline options for an appropriate treatment agenda for addressing the deformity comprehensively over time. Some of these plans may be relatively simple comprising an acute correction of a uniapical deformity. Other cases may require a much more complex plan, including a series of interventions over a number of years such as for an infant with proximal femoral focal deficiency.

Surgical Indications: General

The decision about whether or not to correct a given deformity can be quite individual for each patient and there are no absolute rules. Relative indications for surgical correction of a deformity include the presence of pain or a deformity with a natural history of substantial progression (Table 3.2). In general, current or anticipated limb length discrepancies greater than 2 cm should be addressed.

Table 3.2

Relative indications for surgical correction of lower extremity deformity

Persistent pain |

Mechanical axis in zone 2 with symptoms |

Mechanical axis in zone 3 or greater with or without symptoms |

Uncompensated symptomatic hindfoot deformity |

Sagittal plane deformities impeding gait and function |

Surgical Indications: The Knee

Angulatory deformities about the knee should generally be corrected if the mechanical axis falls within zone 2 and the patient is symptomatic and should be corrected if the mechanical axis is beyond zone 2 (Fig. 3.1) even if the patient is asymptomatic. When the deformity about the knee requires correction, the joint orientation angles such as the lateral distal femur angle (LDFA), the medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), and the joint line congruency angle (JLCA) should be measured. If the JLCA is more than 5° in conjunction with a bony deformity, we prefer to address the ligamentous laxity as well. If the deformity about the knee involves only the femur or the tibia and the other bone is normal, correction should nearly always occur within the affected bone. If both bones are abnormal but the majority of the deformity is within one of the bones, there may be some consideration to correcting only the bone with the majority of the deformity if less than 5° of abnormality is present in either the LDFA or MPTA. If greater than 5° of abnormality is noted in both the LDFA and MPTA, we prefer to address the deformity at both sites.

Fig. 3.1

Depiction of zone of mechanical axis deviation at the knee. Zone 1 is within the tibial spine. Zone 2 is within the tibial condyles. Zone 3 is within the knee joint width away from the center of the knee joint. Zone 4 is greater than one knee joint width from center of knee joint [22]

For sagittal plane deformities about the knee, one must consider both the bony deformity within the distal femur and proximal tibia as well as the soft-tissue constraints about the knee joint. The goal of treatment of sagittal deformity about the knee is functional range of motion in both extension and flexion. My preference is to develop a surgical plan that achieves knee extension within 5° of full extension and without hyperextension of greater than 5° as well as knee flexion of at least 90°. For patients with limited extension, one must consider concomitant hamstring, iliotibial band, or posterior capsule releases while correcting the bony sagittal deformity. Likewise, one can consider quadriceps lengthening to augment a deformity correction in a patient with limited knee flexion.

Surgical Indications: The Ankle

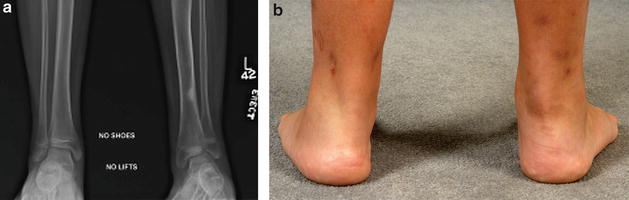

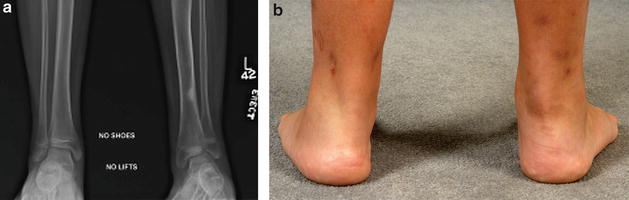

The decision to correct ankle alignment must be made in conjunction with a careful examination of the hindfoot. Patients with substantial deformity of the ankle may be clinically well aligned with a compensatory hindfoot deformity (Fig. 3.2). Patients with such well-compensated deformity and with limited subtalar motion may not be well served by a decision to correct the ankle and thus “create” a more visible deformity by uncovering the fixed hindfoot abnormality.

Fig. 3.2

Radiographs (a) and clinical images (b) of a patient with distal tibial valgus and compensatory hindfoot varus. Note the radiographic valgus of the left ankle and the apparent normal clinical alignment of the left hindfoot

Relative Contraindications

Contraindications to surgery are necessarily somewhat vague and include a number of patient-related factors including unrealistic expectations on the part of the patient and caretakers, their inability to follow through with the necessary outpatient components of a treatment program, as well as situations where the risks of surgical intervention outweigh the potential benefits to the patient (Table 3.3). For instance, patients with severe mental illness or with limited ability to comprehend the treatment plan may not have the ability to comply with more complex treatment protocols including gradual correction using external fixation. Although more complex treatment protocols may be contraindicated in these patients, simplified alternatives may represent better choices. For example, for some patients the difficulties involved in complying with instructions and a physical therapy program associated with a limb lengthening may be able to comply easily with the less strenuous instructions and therapy associated with a closed femoral shortening (Fig. 3.3).

Table 3.3

Relative surgical contraindications to performing lower extremity deformity correction

Unrealistic patient/family expectations |

Patient/family unable to comply with postoperative protocol |

Potential complications of treatment outweigh benefits to patient |

Fig. 3.3

Femoral shortening case study. (a) Preoperative radiographs of a 17-year-old female with a 7 cm left greater than right limb length discrepancy due to a right-sided posttraumatic femoral growth arrest. (b) Intramedullary saw completing distal cut within femur. (c) Intramedullary saw beginning proximal cut within femur 7 cm proximal to distal cut. (d) Completion of proximal intramedullary cut. (e) Intramedullary wedge splitting the medial cortex of the intercalary segment. (f) Completion of splitting intercalary segment. (g) Reduction of proximal and distal segment with solid intramedullary nail. (h) Postoperative radiographs demonstrating healed femur after closed femoral shortening

Surgical Options

The plan for each deformity may comprise any of a number of different techniques that might be applicable in a given situation (Table 3.4). There is no compelling reason to avoid combining techniques when clinically applicable. General categories that should be considered include soft-tissue surgery, physeal bar resection, growth modulation, acute correction with internal or external fixation, or gradual correction with external fixation. A brief description of the techniques follows with a general description of indications and contraindications.

Table 3.4

Available techniques to perform deformity correction

Soft-tissue modification |

Physeal modulation or ablation |

Osteotomy with acute correction |

Osteotomy with gradual correction |

Soft-Tissue Modification

Soft-tissue surgery can be effective either as a solitary procedure or in conjunction with bony surgery. Modification of the soft tissues is not limited to procedures that directly approach the soft tissues themselves but can also be an intended consequence of bony procedures. In particular, tightening of the lateral collateral ligament at the knee can be performed by translating the fibular head distally either with a fibular osteotomy and gradual bone transport with an external fixator or in cases of adolescent tibia vara utilizing a circular external fixator. In these cases a tibial osteotomy can be performed while leaving the fibula intact and securing it distally to the tibia. The angulatory deformity is then corrected while lengthening gradually, thus transporting the fibula distally in relation to the proximal tibia resulting in tightening of the lateral collateral ligament (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4

Case example of adolescent tibia vara treated with circular external fixator and tightening of the lateral collateral ligament. (a, b) AP and lateral preoperative radiographs of a 12-year-old male with tibia vara. (c, d) Immediate postoperative radiographs depicting a ring circular external fixator with fixation of the fibula distally into the tibia and no proximal transfibular fixation. (e) Postoperative radiographs after fixator removal showing distal transport of the fibula relative to the proximal tibia, thus tightening the lateral collateral ligament

Physeal Modulation or Ablation

Physeal modulation can take many forms. Physeal bar resection following traumatic or developmental partial arrest can be performed successfully in situations where a partial arrest of the physis, as documented by progressive deformity, is present that involves less than 50 % of the physis with more than 2.5 cm of growth remaining at the involved physis and more than 2 years of growth expected [2, 3]. Advantages of physeal bar resection include the relative simplicity involved in postoperative care and relatively rapid patient recovery and return to activity (Fig. 3.5). Disadvantages of physeal bar resection include a high failure rate and frequent late closure of the physis necessitating close follow-up and further surgical treatment.

Fig. 3.5

Case example of a 9-year-old female with a posttraumatic physeal bar formation in the right distal femur. (a) Standing AP demonstrating right distal femur physeal bar. (b, c) Coronal and sagittal slice of a CT scan showing lateral distal femoral bar with less than 20 % of physis involvement. (d) Fluoroscopic image showing curettage of physeal bar. (e) Postoperative AP after physeal bar resection. K-wires are placed in order to follow eventual growth; radiolucent cranioplast is placed on the epiphyseal side to limit reformation of bar. (f) Immediate postoperative standing AP. (g) Standing radiographs demonstrating growth within the distal femoral physis 2 years postoperatively. (h) Standing anteroposterior radiograph demonstrating continued growth with migration of the cranioplast proximal to the physis with resultant recurrence of the physeal bar associated with a limb length discrepancy and valgus deformity 3 years postoperatively

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree