Cytomegalovirus

Pablo J. Sánchez

Jane D. Siegel

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has a worldwide distribution and is the most common cause of congenital infections. CMV occurs in 0.4% to 2.4% of all live births. The acquisition of CMV is usually asymptomatic in the immunocompetent host. Once infected, latent virus persists in leukocytes and tissues. Seroprevalence studies indicate that an inverse relationship exists between socioeconomic status and development of infection. CMV seropositivity in women of childbearing age varies in the United States from 45% in higher socioeconomic groups to 70% in crowded areas with substandard living conditions; this figure increases to nearly 100% in developing countries. Two likely sources of primary CMV infection for pregnant women are infected sexual partners and young children in day-care centers. High rates of infection have been observed among young children in Israeli kibbutzim and in day-care centers in Sweden and the United States, where the rate of viruria may be as high as 70% among children aged 2 to 3 years. Serologic studies demonstrate a 30% seroconversion rate among parents whose children shed CMV as compared with no seroconversions among parents whose children do not excrete the virus.

PATHOGENESIS

The transmission of CMV to a fetus or newborn can occur in utero, during delivery, or postnatally. In utero infection occurs transplacentally during maternal viremia. Primary CMV infection acquired during pregnancy is associated with a 40% risk of congenital infection, with more severe fetal effects occurring when maternal infection occurs in the first half of pregnancy. However, symptomatic disease is present in only 10% to 15% of these infants. CMV also can be transmitted to the fetus after reactivation of latent infection in the mother. Approximately 0.2% to 2.0% of infants born to women who are seropositive before becoming pregnant are infected in utero, but they rarely have clinically apparent disease at birth. Concern exists, however, that maternal coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and CMV may promote perinatal transmission of CMV and result in clinically apparent CMV disease in the newborn, even among those born to mothers with recurrent infection. Recent evidence also suggests that maternal reinfection with a different CMV strain can result in symptomatic congenital disease; the frequency of this occurrence currently is not known.

The transmission of CMV to the newborn infant also may occur intrapartum from contact with infected cervical secretions. In the postpartum period, maternal–infant transmission of CMV occurs during breast-feeding, because 20% to 40% of seropositive women shed CMV into their breast milk. Asymptomatic infection occurs in 60% of infants fed infected breast milk and usually is the result of reactivation of CMV infection in a seropositive mother. Breast-feeding is, therefore, an effective means of providing passive–active immunization of the young infant. In preterm infants who lack maternally derived, transplacental CMV IgG antibodies, the transmission of CMV through breast milk has resulted in symptomatic infection.

An important iatrogenic source of CMV infection is the transfusion of blood that has not been treated to remove viable CMV from a seropositive donor to a seronegative infant. Under such conditions, the incidence is 10% to 30% and usually occurs in infants who weigh less than 1,300 g. The risk of infection is related to the volume of transfused blood, number of donors, and elevated complement fixation titers to CMV in donor blood. Horizontal transmission of CMV in a neonatal intensive care unit has been documented, but is rare.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

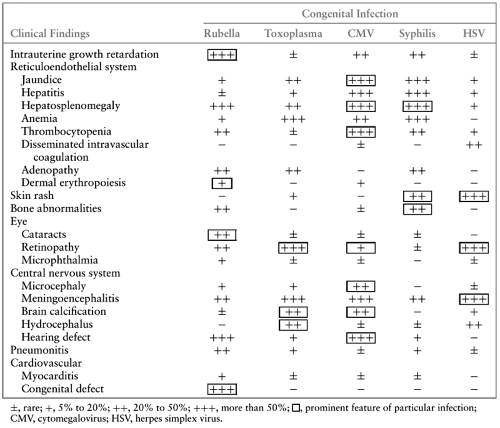

Cytomegalic inclusion disease is the most serious but least common manifestation of congenital CMV infection. This syndrome is characterized by multiorgan involvement, with the reticuloendothelial and central nervous systems most frequently affected. Typical clinical features of cytomegalic inclusion disease include intrauterine growth restriction, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, petechiae or purpura, microcephaly, chorioretinitis, sensorineural hearing loss, and cerebral calcifications (Table 77.1). These features may occur singly or in combination.

Hepatomegaly with direct hyperbilirubinemia and mild elevation of serum transaminase levels are the most common abnormalities noted in the newborn period. Giant cell transformation, with associated extramedullary hematopoiesis or large inclusion-bearing hepatocytes characteristic of CMV infection is present on pathologic examination of the liver. Hepatitis usually resolves in the first year of life, and development of cirrhosis is rare. Splenomegaly is common and may be the only abnormality present at birth. Thrombocytopenia with petechiae usually is transient but may persist through the first year of life. “Blueberry muffin” spots are palpable, discrete, well-circumscribed, bluish purple lesions on yellow jaundiced skin. These are often mistaken for purpura; they represent dermal erythropoiesis in the more severely affected infants (see Color Fig. 82.1 in color section).

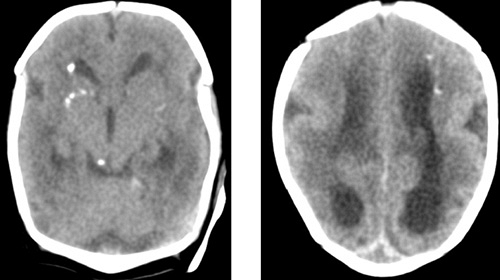

Central nervous system infection with CMV can result in encephalitis and abnormal brain development, with seizures and an elevated protein content in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Cerebral calcifications occur in as many as 50% of newborns with physical examination findings of CMV; their occurrence date the maternal infection to the first trimester of pregnancy. The calcifications typically occur in the periventricular areas (Fig. 77.1), but also may occur within the brain parenchyma and particularly in the basal ganglia (Figs. 77.2 and 77.3). Although these calcifications are best visualized by computed tomography (CT), advances in cranial ultrasonography have provided a readily available and convenient method for their detection. Arrested brain growth results in microcephaly, and obstruction of the fourth ventricle may result in hydrocephalus.

Ocular defects include chorioretinitis (Fig. 77.4), strabismus, optic atrophy, microphthalmia, and cataracts.

Ocular defects include chorioretinitis (Fig. 77.4), strabismus, optic atrophy, microphthalmia, and cataracts.

The most common manifestation of congenital CMV infection is sensorineural hearing loss resulting from direct viral invasion of the inner ear. It occurs in 50% to 60% of infants with symptomatic congenital infection and in approximately 5% of those with otherwise asymptomatic infection at birth. The hearing loss may be unilateral and unsuspected until early childhood, because the majority of CMV-infected, asymptomatic newborns develop hearing impairment beyond the neonatal period. All infants with congenital CMV infection require periodic evaluation of hearing throughout childhood and adolescence in order to detect progressive hearing loss. Cochlear implantation has been used successfully as early as 1 year of age for those children with profound bilateral hearing loss.

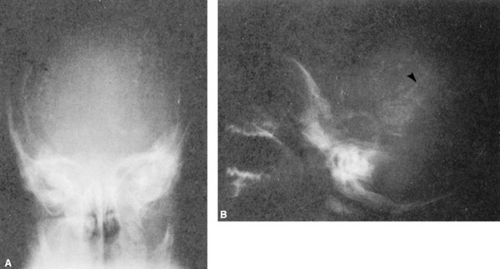

A diffuse interstitial pneumonitis occurs in less than 1% of newborns with cytomegalic inclusion disease. Bone abnormalities in CMV infection consist of longitudinal radiolucent streaks in the metaphysis of long bones (“celery stalk” appearance), particularly the distal femur and proximal tibia (Fig. 77.5). Generalized osteopenia with irregular metaphyseal fragmentation also has been described. Defective enamelization of the deciduous teeth occurs in 40% of symptomatic newborns and in 5% of infants with asymptomatic infection at birth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree