Chapter 424 Cyanotic Congenital Heart Lesions

Lesions Associated with Decreased Pulmonary Blood Flow

424.1 Tetralogy of Fallot

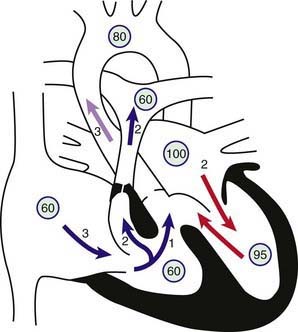

Tetralogy of Fallot is one of the conotruncal family of heart lesions in which the primary defect is an anterior deviation of the infundibular septum (the muscular septum that separates the aortic and pulmonary outflows). The consequences of this deviation are the 4 components: (1) obstruction to right ventricular outflow (pulmonary stenosis), (2) a malalignment type of ventricular septal defect (VSD), (3) dextroposition of the aorta so that it overrides the ventricular septum, and (4) right ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 424-1). Obstruction to pulmonary arterial blood flow is usually at both the right ventricular infundibulum (subpulmonic area) and the pulmonary valve. The main pulmonary artery may be small, and various degrees of branch pulmonary artery stenosis may be present. Complete obstruction of right ventricular outflow (pulmonary atresia with VSD) is classified as an extreme form of tetralogy of Fallot (Chapter 424.2). The degree of pulmonary outflow obstruction determines the degree of the patient’s cyanosis and the age of first presentation.

Pathophysiology

The VSD is usually nonrestrictive and large, is located just below the aortic valve, and is related to the posterior and right aortic cusps. Rarely, the VSD may be in the inlet portion of the ventricular septum (atrioventricular septal defect). The normal fibrous continuity of the mitral and aortic valves is usually maintained, and if not (due to the presence of a subaortic muscular conus) the classification is usually that of double outlet right ventricle (Chapter 424.5). The aortic arch is right sided in 20% of cases, and the aortic root is usually large and overrides the VSD to varying degrees. When the aorta overrides the VSD by more than 50% and if there is a subaortic conus, this defect is classified as a form of double-outlet right ventricle; however, the circulatory dynamics are the same as that of tetralogy of Fallot.

Clinical Manifestations

Infants with mild degrees of right ventricular outflow obstruction may initially be seen with heart failure caused by a ventricular-level left-to-right shunt. Often, cyanosis is not present at birth; but with increasing hypertrophy of the right ventricular infundibulum as the patient grows, cyanosis occurs later in the 1st yr of life. In infants with severe degrees of right ventricular outflow obstruction, neonatal cyanosis is noted immediately. In these infants, pulmonary blood flow may be partially or nearly totally dependent on flow through the ductus arteriosus. When the ductus begins to close in the 1st few hours or days of life, severe cyanosis and circulatory collapse may occur. Older children with long-standing cyanosis who have not undergone surgery may have dusky blue skin, gray sclerae with engorged blood vessels, and marked clubbing of the fingers and toes. Extracardiac manifestations of long-standing cyanotic congenital heart disease are described in Chapter 428.

Diagnosis

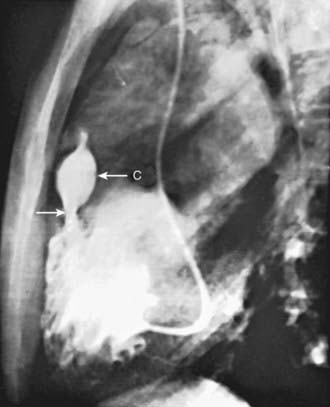

Roentgenographically, the typical configuration as seen in the anteroposterior view consists of a narrow base, concavity of the left heart border in the area usually occupied by the pulmonary artery, and normal overall heart size. The hypertrophied right ventricle causes the rounded apical shadow to be uptilted so that it is situated higher above the diaphragm than normal and pointing horizontally to the left chest wall. The cardiac silhouette has been likened to that of a boot or wooden shoe (“coeur en sabot”) (Fig. 424-2). The hilar areas and lung fields are relatively clear because of diminished pulmonary blood flow or the small size of the pulmonary arteries, or both. The aorta is usually large, and in about 20% of patients it arches to the right, which results in an indentation of the leftward-positioned air-filled tracheobronchial shadow in the anteroposterior view.

The electrocardiogram demonstrates right axis deviation and evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy. A dominant R wave appears in the right precordial chest leads (Rs, R, qR, qRs) or an RSR′ pattern. In some cases, the only sign of right ventricular hypertrophy may initially be a positive T wave in leads V3R and V1. The P wave is tall and peaked suggesting right atrial enlargement (see Fig. 417-6).

Two-dimensional echocardiography establishes the diagnosis (Fig. 424-3) and provides information about the extent of aortic override of the septum, the location and degree of the right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, the size of the pulmonary valve annulus and main and proximal branch pulmonary arteries, and the side of the aortic arch. The echocardiogram is also useful in determining whether a PDA is supplying a portion of the pulmonary blood flow. In a patient without pulmonary atresia, echocardiography usually obviates the need for catheterization before surgical repair.

Selective right ventriculography will demonstrate all of the anatomical features. Contrast medium outlines the heavily trabeculated right ventricle. The infundibular stenosis varies in length, width, contour, and distensibility (Fig. 424-4). The pulmonary valve is usually thickened, and the annulus may be small. In patients with pulmonary atresia and VSD, echocardiography alone is not adequate to assess the anatomy of the pulmonary arteries and MAPCAs. Cardiac CT is extremely helpful, and cardiac catheterization with injection into each arterial collateral is indicated. Complete and accurate information regarding the size and peripheral distribution of the main pulmonary arteries and any collateral vessels (MAPCAs) is important when evaluating these children as surgical candidates.

Complications

Brain abscess is less common than cerebral vascular events and extremely rare today. Patients with a brain abscess are usually older than 2 yr. The onset of the illness is often insidious and consists of low-grade fever or a gradual change in behavior, or both. Some patients have an acute onset of symptoms that may develop after a recent history of headache, nausea, and vomiting. Seizures may occur; localized neurologic signs depend on the site and size of the abscess and the presence of increased intracranial pressure. CT or MRI confirms the diagnosis. Antibiotic therapy may help keep the infection localized, but surgical drainage of the abscess is usually necessary (Chapter 596).

Associated Anomalies

Congenital absence of the pulmonary valve produces a distinct syndrome that is usually marked by signs of upper airway obstruction (Chapter 422.1). Cyanosis may be absent, mild, or moderate; the heart is large and hyperdynamic; and a loud to-and-fro murmur is present. Marked aneurysmal dilatation of the main and branch pulmonary arteries results in compression of the bronchi and produces stridulous or wheezing respirations and recurrent pneumonia. If the airway obstruction is severe, reconstruction of the trachea at the time of corrective cardiac surgery may be required to alleviate the symptoms.

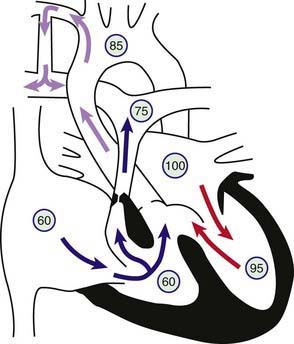

Treatment

The second option, more common in previous years, is a palliative systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt (Blalock-Taussig shunt) performed to augment pulmonary artery blood flow. The rationale for this surgery, previously the only option for these patients, is to augment pulmonary blood flow to decrease the amount of hypoxia and improve linear growth, as well as augment growth of the branch pulmonary arteries. The modified Blalock-Taussig shunt is currently the most common aortopulmonary shunt procedure and consists of a Gore-Tex conduit anastomosed side to side from the subclavian artery to the homolateral branch of the pulmonary artery (Fig. 424-5). Sometimes the shunt is brought directly from the ascending aorta to the main pulmonary artery and in this case is called a central shunt. The Blalock-Taussig operation can be successfully performed in the newborn period with shunts 3-4 mm in diameter and has also been used successfully in premature infants.