Chapter 658 Cutaneous Fungal Infections

Tinea Versicolor

Clinical Manifestations

The lesions of tinea versicolor vary widely in color. In white individuals, they are typically reddish brown, whereas in black individuals they may be either hypopigmented or hyperpigmented. The characteristic macules are covered with a fine scale. They often begin in a perifollicular location, enlarge, and merge to form confluent patches, most commonly on the neck, upper chest, back, and upper arms (Fig. 658-1). Facial lesions are common in adolescents; lesions occasionally appear on the forearms, dorsum of the hands, and pubis. There may be little or no pruritus. Involved areas do not tan after sun exposure. A papulopustular perifollicular variant of the disorder may occur on the back, chest, and sometimes the extremities.

Dermatophytoses

Epidemiology

Occasionally, a secondary skin eruption, referred to as a dermatophytid or “id” reaction, appears in sensitized individuals and has been attributed to circulating fungal antigens derived from the primary infection. The eruption is characterized by grouped papules (Fig. 658-2) and vesicles and, occasionally, by sterile pustules. Symmetric urticarial lesions and a more generalized maculopapular eruption also can occur. Id reactions are most often associated with tinea pedis but also occur with tinea capitis.

Tinea Capitis

Clinical Manifestations

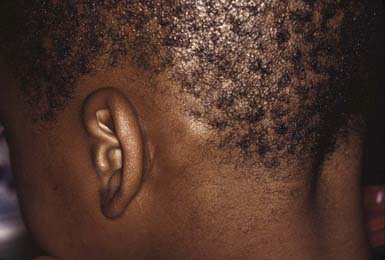

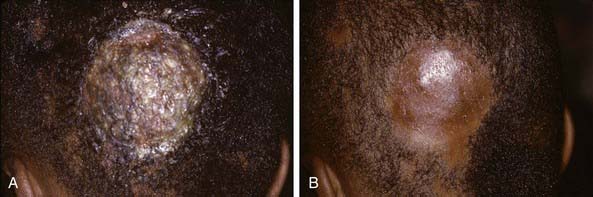

The clinical presentation of tinea capitis varies with the infecting organism. Endothrix infections such as those caused by T. tonsurans create a pattern known as “black-dot ringworm,” characterized initially by many small circular patches of alopecia in which hairs are broken off close to the hair follicle (Fig. 658-3). Another clinical variant manifests as diffuse scaling, with minimal hair loss secondary. It strongly resembles seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or atopic dermatitis (Fig. 658-4). T. tonsurans may also produce a chronic and more diffuse alopecia. Lymphadenopathy is common (Fig. 658-5). A severe inflammatory response produces elevated, boggy granulomatous masses (kerions), which are often studded with pustules (Fig. 658-6A). Fever, pain, and regional adenopathy are common, and permanent scarring and alopecia may result (Fig. 658-6B). The zoophilic organism M. canis or the geophilic organism Microsporum gypseum also may cause kerion formation. The pattern produced by Microsporum audouinii, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the 1940s and 1950s, is characterized initially by a small papule at the base of a hair follicle. The infection spreads peripherally, forming an erythematous and scaly circular plaque (ringworm) within which the infected hairs become brittle and broken. Numerous confluent patches of alopecia develop, and patients may complain of severe pruritus. M. audouinii infection is no longer common in the USA. Favus is a chronic form of tinea capitis that is rare in the USA and is caused by the fungus Trichophyton schoenleinii. Favus starts as yellowish red papules at the opening of hair follicles. The papules expand and coalesce to form cup-shaped, yellowish, crusted patches that fluoresce dull green under a Wood lamp.