Chapter 8 Course and management of childbirth

CHOICES IN CHILDBIRTH

With the trend towards hospital birth in the developed countries, some groups of women question whether this is always appropriate, claiming that on admission to hospital a pregnant woman loses her autonomy, may not be told about proposed procedures, and can be treated impersonally by busy attending staff. In other words, a normal event is medicalized. Several international organizations have addressed the issues raised by women and made recommendations, which are summarized in Box 8.1.

Box 8.1 Childbirth recommendations

The criticisms advanced by women’s groups have had an effect on obstetric practice and the childbirth choices now provided in many places (Box 8.2).

Prepared participatory childbirth

In this approach the parents undertake childbirth training, learning about the processes of childbirth and how to accept the pains of uterine contractions (see pp. 49–50). Labour is managed by trained staff, and the principles mentioned earlier are observed by both staff and patients. The birth takes place in a quiet environment and the baby is given to the mother at once so that she may offer suckling and celebrate the birth.

Actively managed childbirth

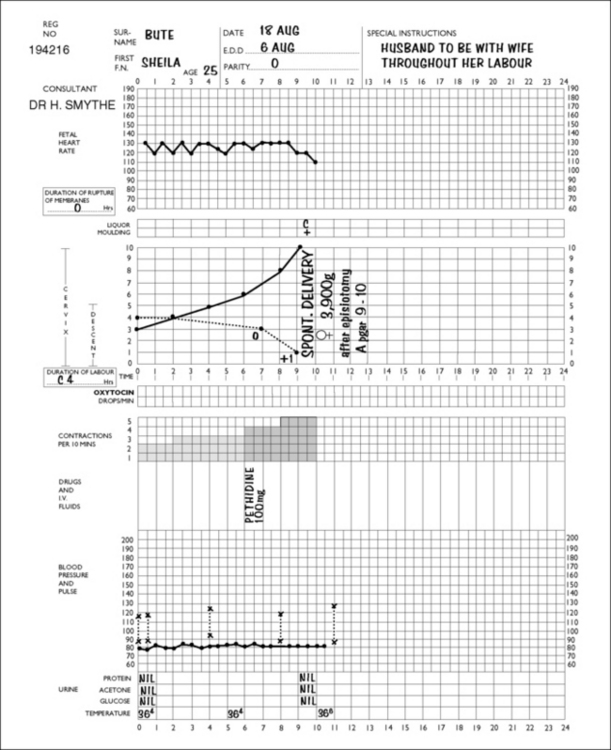

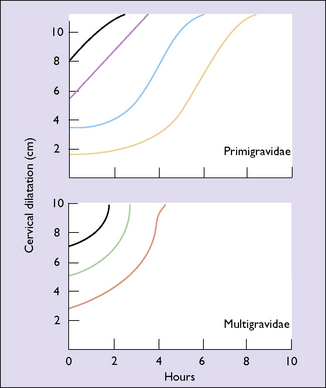

On admission to the delivery unit, the diagnosis of labour is either confirmed or rejected. If the woman is in labour, the time of admission is designated as the start of labour. A partogram is started and the progress of labour is marked on it (Fig. 8.1). Vaginal examinations are made every 2–4 hours and the cervical dilatation is recorded on the partogram. Action lines, printed on transparent plastic, are superimposed on the partogram (Fig. 8.2). In the active stage of labour the slowest acceptable rate of cervical dilatation is 1 cm/h. If the cervical dilatation lies to the right of the appropriate action line the membranes are ruptured and an incremental dilute oxytocin infusion is established in nulliparous women (and some multiparous women), provided that a single fetus presents as a vertex and there are no signs of fetal distress.

Elective caesarean section

A small but increasing number of women, particularly those over the age of 35, inform their obstetrician during pregnancy that they wish to be delivered by caesarean section. The obstetrician should listen to the woman and discern the underlying reasons for her request. For some it may be a fear of the pain of labour, for others to avoid any risk of pelvic floor damage during delivery, or a perception that abdominal delivery removes all risks for the baby. It is particularly important that the risks of caesarean versus vaginal delivery are carefully explained (Box 8.3). If the woman confirms that she wishes to be delivered by caesarean section, the obstetrician should either agree to her wish or arrange for a consultation with another colleague.

Box 8.3 Effects of caesarean section compared with vaginal birth

Adapted from Caesarean Section, National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. 2004. RCOG Press www.rcog.org.uk. Full details of absolute and relative risks can be obtained from full guideline.

| Increased | No difference | Decreased |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | Blood loss >1000 ml | Perineal pain |

| Bladder and ureteric injury | Infection-wound or endometritis | Urinary incontinence |

| Need for laparotomy or D&C | Genital tract injury | Uterovaginal prolapse |

| Hysterectomy | Back pain | |

| ICU admission | Dyspareunia | |

| Thromboembolism | Postnatal depression | |

| Length of hospital stay | Neonatal morbidity (excluding breech) | |

| Readmission | Neonatal intracranial haemorrhage | |

| Placenta praevia | Brachial plexus palsy | |

| Uterine rupture | Cerebral palsy | |

| Maternal death | ||

| Stillbirth in future pregnancies | ||

| Secondary infertility | ||

| Neonatal respiratory morbidity |

ONSET OF LABOUR

Onset of true labour

Duration of labour

The duration of labour is not easy to determine precisely as its onset is often indefinite and subjective (Box 8.4). In studies of informed women whose labour started spontaneously there was a wide variation in the duration of labour, as can be seen in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Duration (and range) of labour (in hours)

| NULLIPARAE | MULTIPARAE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st stage | 8.25 (2–12) | 5.5 (1–9) |

| 2nd stage | 1 (0.25–1.5) | 0.25 (0–0.75) |

| 3rd stage | 0.25 (0–1)9.5 (2.25–14) | 0.25 (0–0.5)6 (1–10.25) |

PROGRESS AND MANAGEMENT OF LABOUR AND BIRTH

The management of labour begins when the woman seeks admission to hospital, which she does when she believes or knows that she is in labour. As labour is a time of anxiety and stress, the attitude of the member of staff who admits her is most important. The care of the woman during her labour and childbirth may be conducted by a midwife (see also p. 66), or by midwives in partnership with an obstetrician or a general practitioner.

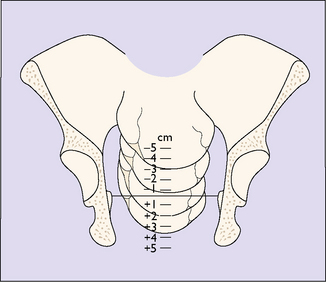

Admission

A general examination is made by a midwife or a doctor, the blood pressure, pulse and temperature being recorded. The abdomen is palpated to determine the presentation of the fetus and the position of the presenting part in relation to the pelvic brim (see Fig. 6.17). A vaginal examination may be carried out, with aseptic precautions, to determine the effacement and dilatation of the cervix and the position and station of the presenting part. The station of the presenting part is the level of the lowest fetal bony part (head or breech) in relation to an imaginary line joining the mother’s ischial spines. It is measured in centimetres above or below the ischial spines (Fig. 8.3). If the amniotic sac (the membranes) has ruptured this is noted. Evidence does not support the common practice of performing a routine 20-minute cardiotocogram (CTG) on admission in low-risk women. The ‘admission CTG’ is associated with higher intervention rates, i.e. augmentation of labour, epidural analgesia and operative delivery, without a clear improvement in neonatal outcome. The woman is transferred from the admission room to a bed in a delivery room (if she has not already been admitted to it) and a partogram is started which shows the progress of labour at a glance.