Control of Pelvic Hemorrhage

Robert E. Bristow

INTRODUCTION

The most effective strategy to control pelvic hemorrhage is to prevent it in the first place through diligent preoperative preparation, sound surgical judgment, and the use of careful and meticulous surgical technique. Nevertheless, significant pelvic hemorrhage is a potential complication in any patient undergoing gynecologic or obstetrical surgery. Intraoperative, postoperative, or postpartum bleeding can occur as a result of unexpected or unrecognized vascular injury or an inability to control excessive bleeding during a surgical procedure. Effective management of pelvic hemorrhage requires an expert knowledge of pelvic anatomy and the relevant vascular supply, as well as the coagulation system, with its intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Immediate recognition and prompt response to pelvic hemorrhage can minimize the sequelae of this life-threatening complication.

The pelvic surgeon will encounter a number of clinical scenarios that may be complicated by significant pelvic hemorrhage, the more common of which include: uncontrolled bleeding from a uterine incision, typically at cesarean section, diffuse central pelvic bleeding as a result of extensive surgery for malignancy or infection, and direct injury or laceration of a pelvic artery or vein during extensive dissection (e.g., lymphadenectomy and surgery for severe endometriosis). The pelvic surgeon should be familiar with the techniques of uterine artery ligation, hypogastric (internal iliac) artery ligation (HAL), repair of vascular injury, and packing outlined in this chapter. In addition, the surgeon should be able to institute corrective measures for abnormalities in the coagulation system and selectively employ intravascular embolization techniques by interventional radiology, when appropriate, to control pelvic hemorrhage.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Although significant hemorrhage is a risk in any surgical procedure, the presence of certain risk factors should prompt a higher level of anticipation and preparation: 1) any cesarean section, especially if it involves repeat surgery or a risk of uterine atony; 2) surgery for extensive pelvic malignancy, particularly involving deep pelvic structures or the pelvic retroperitoneum; 3) surgery for severe pelvic infection (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess) or endometriosis, with obliteration of normal tissue planes compounding the difficulty of dissection; 4) obesity; 5) the presence of a large pelvic mass; 6) prior pelvic radiation treatment; and 7) coagulation dysfunction. In these circumstances, the surgeon can enhance his or her capacity to deal with hemorrhage, should it occur, by ensuring that the following instrumentation is close at hand: additional suction devices, electrosurgical unit (ESU or “Bovie”), an argon beam coagulator, vascular hemoclips (medium and large), vascular clamps (e.g., “bulldog” and Satinsky), and fine (5-0) monofilament suture with a vascular needle. It may also be advisable to have access to hemostatic agents that can be used to help control diffuse venous oozing such as oxidized, regenerated cellulose (Surgicel®, Ethicon, San Angelo, TX), absorbable gelatin foam (Gelfoam®, Pfizer, New York, NY),

microfibrillar collagen (Avitene®, Bard Davol, Murray Hill, NJ), and fibrin glue (Floseal® hemostatic matrix, Baxter, Deerfield, IL). Preparations should be made with the blood bank to ensure the availability of type and cross-matched packed red blood cells as well as component therapy (e.g., cryoprecipitate and platelets) to replace specific deficiencies that may be associated with massive hemorrhage.

microfibrillar collagen (Avitene®, Bard Davol, Murray Hill, NJ), and fibrin glue (Floseal® hemostatic matrix, Baxter, Deerfield, IL). Preparations should be made with the blood bank to ensure the availability of type and cross-matched packed red blood cells as well as component therapy (e.g., cryoprecipitate and platelets) to replace specific deficiencies that may be associated with massive hemorrhage.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

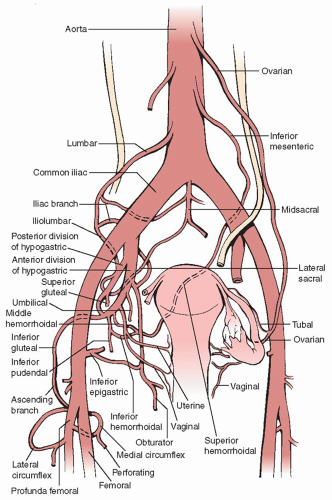

A general prerequisite to the effective control of pelvic hemorrhage is an expert knowledge of the pelvic vasculature and the relationships to critical surrounding structures (Figure 21.1). In the face of significant pelvic hemorrhage, the initial effort should be directed at locating the source of bleeding and applying pressure either with a fingertip, a spongestick, or laparotomy packs. Direct pressure will stem the hemorrhage and allow the surgeon to get organized for more definitive management. The surgeon must resist the urge to try and get the bleeding quickly under control by blindly applying traumatic clamps, using electrocautery indiscriminately, or placing sutures or clips without precise localization of the vascular injury.

After pressure control has been established, the surgeon should quickly and efficiently: 1) notify the anesthesia team of the situation and consult with them on the proposed plan of management (including adequate

intravenous access and the possible need for ICU care postoperatively); 2) call for blood bank resources (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and whole blood) for possible transfusion; 3) gather the necessary instrumentation and equipment; and 4) request additional surgical assistants or specialized personnel (e.g., vascular surgeon), if necessary.

intravenous access and the possible need for ICU care postoperatively); 2) call for blood bank resources (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and whole blood) for possible transfusion; 3) gather the necessary instrumentation and equipment; and 4) request additional surgical assistants or specialized personnel (e.g., vascular surgeon), if necessary.

Next, the adequacy of exposure of the operative field should be evaluated. Sufficient lighting should be assured. The adequacy of the incision and surgical approach should be reassessed; a vertical incision may need to be extended, a Pfannenstiel incision may need to be converted to a Cherney incision, or a laparoscopic or vaginal procedure may need to be converted to laparotomy. Retractors may need to be added or replaced. The surgical field should be cleared of excess instrumentation and packs, and any blood clot should be evacuated. To the greatest extent possible, the surgeon should normalize anatomy around the site of bleeding and mobilize and retract nearby vulnerable structures (e.g., bladder, ureter, and other vessels). At this point, the pressure control measures can be carefully withdrawn to identify the source of hemorrhage and allow the surgeon to assess the situation and formulate an appropriate plan of action (e.g., use of clamps, suture ligatures, electrosurgical sealing, hemostatic agents, or a combination of measures).

Uterine artery ligation

Uterine artery ligation is appropriate for cases of significant bleeding from the uterine incision at cesarean section, either intraoperatively or postoperatively, and uterine bleeding complicating an extensive abdominal myomectomy procedure. The technique is straightforward and can rapidly arrest uncontrolled bleeding from the cesarean section uterine incision. In their original report, O’Leary and O’Leary reported a success rate of over 90% in controlling postcesarean hemorrhage with this technique, such that hysterectomy was necessary in just 4 of 90 cases.

Uterine artery ligation is most easily performed with the surgeon standing on the patient’s left side. The uterus is grasped and elevated with the surgeon’s left hand. To ligate the left uterine artery, a No. 1 or 1-0 delayed absorbable or chromic catgut suture on a large needle is passed into and through the myometrium 1 cm medial to the uterine vessels at the level of the uterine isthmus, driving the needle from anterior to posterior. The needle is brought forward through the avascular area of the broad ligament 2 to 3 cm lateral to the uterine vessels and the knot tied on the ventral surface. To ligate the right uterine artery, the needle is passed first through the avascular area of the broad ligament 2 to 3 cm lateral to the uterine vessels, anterior to posterior, then it is brought anteriorly through the myometrium 1 cm medial to the uterine vessels, and the knot is tied on the ventral surface (Figure 21.2). With proper placement of the ligatures at the level of the uterine isthmus, there is negligible risk of bladder or ureteral injury and no need for extensive bladder mobilization or ureteral dissection. Generally, the ligatures should be placed below the level of the transverse uterine incision for maximal control of bleeding. If bleeding from the uterine incision persists, the collateral blood supply to the uterus from the ovarian vessels should be controlled by placing a No. 1 or 1-0 delayed absorbable suture in a figure-of-eight stitch through the utero-ovarian ligament on each side.

Hypogastric artery ligation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree