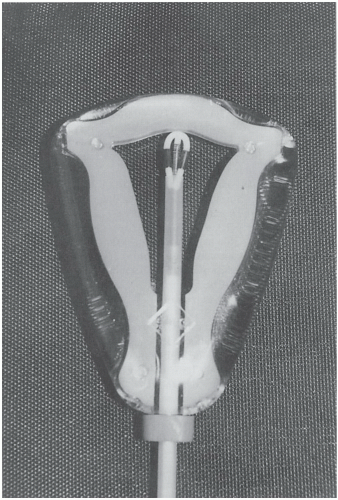

The levonorgestrel (LNG)-releasing IUD (Mirena) releases 20 mcg LNG daily. It inhibits sperm transport, thickens cervical mucus, partially inhibits ovulation, and causes reversible atrophy of the lining. These actions reduce menstrual flow by 70% at 6 months and by 90% at 12 months.

30 Amenorrhea is seen in 30% of users by 2 years of use.

31,

32,

33 The Mirena also improves dysmenorrhea so its use may be preferable in women experiencing heavy or painful periods. The Mirena IUD has been approved for 5 years of use but may be effective for up to 7 years. Two large clinical trials in Finland and Sweden with more than 1600 women and 45,000 cycles of use have demonstrated cumulative 5-year pregnancy rates of less than 0.7 per 100 women.

34Although irregular spotting or bleeding may occur in the first few months, this usually diminishes over time. The majority of women who continue to have cyclical menses with the LNG IUD have ovulatory progesterone levels, but only 58% of these women have normal growth and rupture of ovarian follicles on ultrasound exam. Of the women who do not have cyclical menses, 29% have growth and rupture of follicles.

35 It is not surprising then that women using the LNG IUD can develop large (greater than 3 cm) ovarian cysts. In one study, all these cysts spontaneously resolved over a 4-month period, and it is believed the formation of these cysts is of limited significance.

36 These findings are similar to what has been seen with the subdermal LNG implants.

37 As eluded to earlier, there are a host of noncontraceptive benefits with the LNG IUD. In addition to treatment for menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea, it can be used to protect the endometrium from effects of unopposed estrogen.

Complications Associated With IUD Use

The risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is about 1/1000 and occurs in the first 20 days postinsertion. Women at risk are those with bacterial vaginosis and cervicitis. These infections should be treated with the IUD in place. Uterine perforation is also 1/1000 and is more common with immobile or anteverted or retroverted uteri, lactating women, and inexperienced inserters.

LNG IUD expulsion is more common in younger women, women who have not had children, and when an IUD is inserted immediately after childbirth or abortion. There is a higher risk of expulsion for women who have never given birth.

38 LNG IUD expulsion rate is about 3% when used exclusively for contraception and 9 to 14% when used to control bleeding.

39,40 IUDs decrease the rate of ectopic pregnancy compared with no contraception. However, if pregnancy occurs, the risk of an ectopic pregnancy is increased and the patient should be evaluated immediately.

When pregnancy is diagnosed in the presence of an IUD, the location of the pregnancy (intra- or extrauterine) should be determined and the device removed as soon as possible in the first trimester. Septic abortion is greatly increased when pregnancy is complicated by IUD. Women who become pregnant with an IUD in place have a 50% increased rate of spontaneous abortion. After removal of the IUD, the spontaneous abortion rate decreases to about 30%. If it cannot be removed or she chooses not to have it removed, she should be counseled that in addition to the increased spontaneous abortion rate, the risk of preterm labor, delivery, and sepsis are increased. She can be reassured that there is no increase in congenital anomalies.

Removal of an IUD in an infected, pregnant uterus should be accomplished only after intravenous antibiotic blood levels have been achieved. The removal of the IUD should be done in a location where emergency measures are available, in case septic shock ensues.

The IUD can be inserted safely at any time after abortion or delivery. There is a higher rate of expulsion for the delayed postpartum insertions, although it can be prevented with high fundal placement. Additionally, the rate of expulsion is lower for immediate postpartum insertions (within 10 minutes of placental delivery) than for delayed insertions (within 48 hours of delivery).

22 Insertion of the IUD during the period of lactational amenorrhea has the advantage of significantly decreasing the spotting problem often encountered during the first cycle after insertion. Directions for placement of the copper and progesterone IUDs are found in

Appendices 1.A and

1.B.

The patient should check for the IUD string monthly, and the practitioner should check for it at the time of gynecologic examination. If twirling a cytobrush in the cervical canal does not bring the strings into view, an ultrasound should be done to confirm intrauterine location. If the ultrasound does not show it, a flat plate abdominal radiograph can be taken, with an abdominal series to triangulate the location. If the IUD is intra-abdominal/extrauterine, it must be physically retrieved. An intra-abdominal IUD can cause serious problems, including bowel obstruction or perforation. Removal should be done as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made. Copper IUDs, in particular, elicit a strong inflammatory response that may make laparoscopic removal quite difficult. Perforation of the uterus usually occurs at the time of insertion, so it is important to identify the strings a few weeks afterward.

To remove an IUD, the strings are grasped with either a ring forceps or uterine dressing forceps and firm traction is exerted. If the string(s) cannot be seen, a cytobrush in the endocervical canal may help in extracting them. If ultrasound confirms intrauterine location, a paracervical block can be given before using alligator forceps or other instruments in the uterus. Visualization of the IUD with sonography or hysteroscopy may be necessary to facilitate removal.