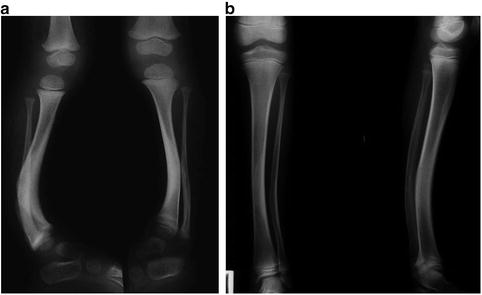

Fig. 26.1

Congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia in a newborn. The clinical and radiographic appearances of the posterior bow (a, b) and the medial bow (c, d) are clearly seen. A delay in the ossification of the proximal tibial epiphysis and the cuboid is evident

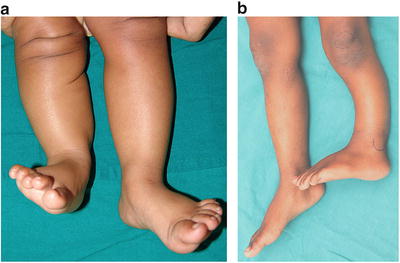

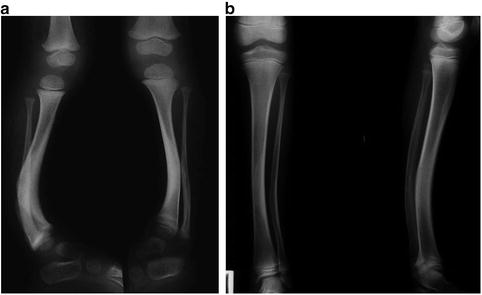

Fig. 26.2

Examples of a short tibia associated with congenital posteromedial bowing. The shortening is mild when the bowing is mild (a) and greater when the bowing is more severe. Occasionally, a torsional deformity may also be present (b). The patella and lateral malleolus have been marked to demonstrate the torsional deformity

Though the degree of shortening frequently is in the order of 15 or 20 % up to 40 % of shortening has been recorded [10]. Occasionally there may be an associated torsional deformity of the tibia (see Fig. 26.2b).

The Fibula

The fibula is also bowed and the degree of deformity parallels the tibial deformity. The distal fibula physis is often at a higher level than normal suggesting that there is a relative growth retardation of the fibula as compared to the affected tibia (Fig. 26.3).

Fig. 26.3

The fibular physis is at a higher level than normal (at the level of the ankle joint)

The Ankle and Foot

The tibial deformity is invariably associated with a calcaneo-valgus deformity which may be very severe at birth with the dorsum of the foot lying almost in contact with the shin (Fig. 26.4). The distal tibial epiphysis may appear late and when it does appear it may be eccentrically positioned towards the medial side (Fig. 26.5a) [10]. The epiphysis may then develop asymmetrically into a wedge-shaped epiphysis (see Fig. 26.5b) resulting in a valgus tilt of the ankle mortise [10]. The growth delay of the fibula with a high lateral malleolus referred to above also contributes to ankle valgus.

Fig. 26.4

Calcaneo-valgus deformity seen in association with congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia

Fig. 26.5

Eccentric ossification of the distal tibial epiphysis in a toddler with congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia (a) and a wedge-shaped distal tibial epiphysis in an older child with congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia (b). The valgus tilt of the ankle becomes more evident as the child grows older (c)

Box 26.1. The Deformity

Posteromedial bowing at the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the tibia and fibula.

Posterior bow is usually more severe than medial bow.

Shortening is proportionate to severity of bowing.

Always associated with a calcaneo-valgus deformity of the foot.

Valgus deformity of the ankle may develop later due to growth abnormalities of the distal tibia and fibula.

The Natural History

Rate and Pattern of Spontaneous Remodeling

The posteromedial bowing deformities of the tibia and fibula tend to improve spontaneously over time. The resolution of the bony deformity occurs by two distinct mechanisms; one entails resorption of bone from the convex surface and new bone deposition on the concavity of the bow in accordance with Wolff’s law [10]. De Maio et al. demonstrated that this pattern of remodeling begins in utero [7]. At 24 weeks of gestation an abundance of osteoclasts were present at the apex of the deformity while an osteoblastic response was seen in the concavity. As this process of remodeling progresses the angular deformity decreases and the angulation between the proximal and distal segments of the bone diminishes. The second mechanism of spontaneous correction of the deformity involves realignment of the proximal and distal growth plates. Physeal reorientation occurs at a faster rate than remodeling at the site of the deformity [10]. Remodeling of the deformity by both these mechanisms occurs at a rapid rate during the first year of life and thereafter the rate of remodeling decreases quite substantially dropping to half the initial rate (Fig. 26.6) [10].

Fig. 26.6

The rate of spontaneous resolution of bowing is rapid in the first year of life, slows down thereafter, and reaches a plateau by 4–5 years of age

Residual Deformities, Shortening, and Functional Problems

Complete resolution of the diaphyseal deformity does not occur in a proportion of children and residual deformity that is clinically discernable may be seen in children older than 4 or 5 years of age (Fig. 26.7a, b) [10].

Fig. 26.7

Residual posterior bowing of both tibiae in a child aged 4 years with bilateral posteromedial bowing of the tibia (a) and residual bowing at 8 years in another child (b). The AP radiograph shows that the distal tibial articular surface is not parallel to the plane of the knee joint even though the medial bow has remodeled to a very large extent

Shortening of the limb increases with growth [8] and the limb length discrepancy at skeletal maturity may frequently be of a magnitude to warrant treatment. Pappas noted a median shortening of 4.1 cm at skeletal maturity with a range between 3.3 and 6.9 cm [5]. The foot length of the affected limb is often less than the normal foot [5, 8, 12].

Limitation of ankle motion may persist; limitation of both plantar flexion and dorsiflexion has been reported [8, 10].

Weakness of plantar flexion (Fig. 26.8) has been observed in some children even though the bony deformity may have remodeled almost completely [10]. On occasion the weakness of the gastrocsoleus may be severe enough to result in a calcaneal hitch and a visible gait abnormality requiring surgical intervention [10]; we have encountered two such children.

Fig. 26.8

The power of plantar flexion is being tested in a boy with congenital posteromedial bowing of the tibia. Weakness of plantar flexion on the effected side is clearly evident. This weakness that was present before he underwent corrective osteotomy for residual deformity still persists

Box 26.2. Spontaneous Resolution of Bowing

Occurs by local remodeling and by physeal realignment.

Occurs rapidly in the first year of life.

Little remodeling occurs after 4–5 years of age.

Complete resolution may not occur.

Evaluation

Establishing the diagnosis is not difficult once the plane of the deformity is clear. The evaluation should include a careful documentation of the clinical estimate of the severity of the diaphyseal deformity in the coronal and sagittal planes. The foot should be passively plantar flexed and inverted to assess the rigidity of the calcaneo-valgus deformity. Anteroposterior and lateral full-length plain radiographs of both tibias and a scanogram should be taken to facilitate accurate estimation of the angulation and shortening. The degree of shortening of the tibia should be documented and expressed both as a percent of the normal tibial length and in centimeters. The extent of bowing should be estimated by measuring the diaphyseal angle and the inter-physeal angles on the radiographs (Fig. 26.9). The parents should be counselled and reassured that the deformity will reduce spontaneously but they need to be warned that complete resolution may not occur. They should also be instructed in performing passive stretching exercises of the foot into plantar flexion and inversion and encouraged to do it at least twice a day.