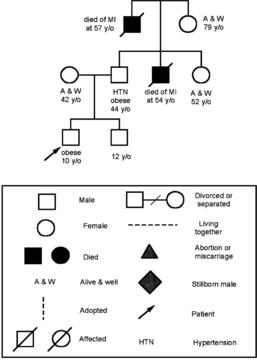

CHAPTER 4 Information gathered from the family history is also key to identifying genetic patterns of inheritance in health conditions and is a guide to health education and promoting responsible health behaviors in the child and adolescent.1 Identifying and counseling children and adolescents at risk for chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease begins with gathering a comprehensive family history.1 Identifying and counseling for childhood overweight and obesity remains a top priority in pediatrics. Identifying early childhood factors in the comprehensive history that are significant predictors of obesity in adulthood is an important role for pediatric health care providers in prevention and anticipatory guidance. Probable early markers of obesity include maternal body mass index; childhood growth patterns, particularly early rapid growth and early adiposity rebound; childhood obesity; and parental employment, a marker for socioeconomic status of the family.2 When gathering the health history, it is important to talk to children and adolescents about the importance of physical activity and their dietary routines to establish early positive health habits. The comprehensive health history in children and adolescents also includes psychosocial screening. In child health, the top five chronic health conditions in pediatrics currently are speech and language delays, learning disabilities, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, developmental disabilities, and emotional, behavioral, and mental health problems.3 These findings indicate the importance of psychosocial screening during every well-child and adolescent encounter in a clinical setting. Another important component of comprehensive information gathering is oral health. Tooth decay continues to be the single most common chronic health condition in pediatrics. Tooth decay affects more than one fourth of U.S. children from 2 to 5 years of age and half of adolescents 12 to 15 years of age.4 Globally, 60% to 90% of school children have dental caries.5 Assessing children’s oral health and access to dental health services is key to establishing positive dental health behaviors early in life. Genetics has transformed the use of family history information and has led to the reemergence of the detailed genetic family history. The increased use of genetic screening is creating a paradigm shift in medical treatment by emphasizing primary prevention and early intervention for families with hereditarily linked health conditions.6 Gathering of the comprehensive family history is necessary to make this link and advance the health of children and families. It is important to be aware of the emotional and ethical issues that may arise when taking a genetic family history, such as the hereditary link between breast cancer in female relatives and familial gene testing. Pediatric health care providers are well placed to provide this support to individuals and families.7 Also, pediatric providers are particularly well positioned to use this knowledge as they provide primary care for children from birth to young adults, the period during which many genetic disorders emerge.1 An accurate genetic family history requires the availability of a reliable family source and the knowledge of a three-generation family history. The challenge is to gather a family and genetic history within the brief time available in the clinical setting. Table 4-1 presents the SCREEN mnemonic for an initial genetic family history.8 The SCREEN mnemonic represents an initial series of questions used to quickly identify potential genetically influenced health conditions in the family that require further intervention, counseling, referral, or screening by a geneticist. Figure 4-1 is an example of a family pedigree with a multigenerational inheritance of cardiovascular disease. TABLE 4-1 The SCREEN Mnemonic for Family History Collection From Trotter TL, Martin HM: Family history in pediatric primary care, Pediatrics 120(Suppl 2):S60-65, 2007. FIGURE 4-1 Family pedigree with a multigenerational inheritance of cardiovascular disease. (From Bennett RL: The practical guide to the genetic family history, New York, 1999, Wiley-Liss, Inc.) • Listen actively to the concerns of the family. A caring relationship is established by developing an understanding of the feelings and values within the family context. • Understand the family expectations for the encounter. To successfully establish a caring relationship, the parent’s agenda must be identified and addressed during the encounter. • Ask open-ended questions, thereby allowing relevant data to unfold. • Personalize your care. Ask about the health and well-being of other family members and extended family members to personalize your care and demonstrate your connectedness with the family unit. Taking the time to obtain and integrate this relevant personal data on the child and family will assist in building the family profile and family-centered relationship. • Learn and understand the role and importance of cultural influences in the family and the primary language spoken in the home. The health interview should be conducted in the family’s primary language if possible to promote family engagement. • Identify protective factors in the family that create a positive environment for the child. Social supports for the parents, involvement of relatives or extended family, and shared family interest in activities such as sports, cultural events, or religious services often help to form a supportive and protective community for children and adolescents. • Build a sense of confidence in parents by confirming and complimenting their strengths in caring for their child. This approach also builds a trusting relationship between the family and health care provider. • Time management is key. With the increased workload in health care settings and the implementation of electronic health records, being present when talking with children and families becomes more challenging. Remember to sit rather than stand, maintain eye contact with the child and family in between screen time, and share screen health information such as growth chart and lab results to engage with families. Pediatric health care providers are uniquely suited to assess children from a family-centered perspective. Box 4-1 approaches the family-centered interview from three levels to assess family strengths, stressors, and threats to the family unit. Families hold trust in the pediatric provider, and their relationship is based on the knowledge, understanding, respect, and care the pediatric provider demonstrates during the encounter with their child. • Where was the child born? If an immigrant: How long has the child lived in this country? What is the family’s cultural identity? • If multiracial family: What culture(s)/race(s) does the family identify with most closely? If interviewing an adolescent: What culture(s)/race(s) do you identify with most closely? • What are the child’s primary and secondary languages? What is the family’s speaking and reading ability of the primary language (languages) in the home? • What is the family’s religion, and do they practice their religion daily or weekly? • Are the family’s food preferences linked to cultural or religious preferences? • Are there beliefs about health or illness related to the family’s culture? • If interviewing an adolescent: Are there conflicts with parents or peers concerning cultural norms or customs? Have you experienced discrimination? The type of health history gathered during an encounter depends on whether the child and family are presenting for a comprehensive well-child visit, acute care visit, symptom-focused visit, or a preparticipation sports physical examination (see Chapter 18). Examples of medical charting and electronic medical record (EMR) templates for different types of health visits for different pediatric age groups are presented in Chapter 20. • When did you first notice the symptoms? Or date/time child was last well? • Character of symptoms (time of day, location, intensity, duration, quality)? • Progression of symptoms (How is child doing now? Symptoms getting better or worse?) • Associated symptoms (vomiting, fever, rash, cough etc.)? Anything else bothering child? • Exposure to household member, classmates, or others who have been ill? Pets in home? • Changes in appetite or activity level (eating regularly, school/daycare attendance, sleeping pattern)? • Medications taken (dosage, time, date)? Did the medication help or relieve the symptoms? • Home management (What has the family tried? What has helped?) Use of alternative therapies or healing practices? • Pertinent family medical history? (Is anyone in the family immunosuppressed or does anyone have a chronic illness?) • What changes have occurred in the family as a result of this illness (effects or secondary gain)? • Has the family seen other health care providers for the concern? • GTPAL (Gravidity, number of pregnancies; Term deliveries; Premature deliveries; Abortions, spontaneous or induced; Living children) • Maternal and paternal age, month prenatal care started, planned pregnancy? • Length of pregnancy, weight gain, history of fetal movement/activity • Maternal health before and during pregnancy—overweight or obese; hypertension; gestational diabetes; infectious diseases, including TB and HIV status; asthma or other chronic health conditions; hospitalizations • Maternal substance use or abuse; tobacco use; prescription drug use; over-the-counter drug use or abuse; intimate partner violence or exposure to abuse or family violence • Length of labor, location of birth, cesarean or vaginal delivery, epidural/anesthesia? Vacuum-assisted vaginal birth? Breech or shoulder presentation? • Infant born on or near expected due date? Born preterm or post term? If preterm: Was infant in intensive care? Intubated? • Birth weight and length? Gestational age? • Apgar score, if known? Breathing problems after birth? • Who was present at delivery, how soon after birth did mother or parent(s) touch or hold baby? • Difficulties in feeding or stooling? Irritability or jitteriness? Jaundice? • Length of hospitalization? Was infant discharged with mother? • Childhood conditions: Frequent upper respiratory infections (URIs) or viral infections, history of ear infections—how often? Sore throats; streptococcal or bacterial infections? Eczema or frequent skin rashes? Dental caries? • Chronic conditions: Seasonal or household allergies, wheezing or asthma; recurrent bronchitis; frequent ear infections or fluid in ears; hearing problems; overweight or obesity; diabetes; bed-wetting; dental decay or poor oral health? HIV or immunodeficiency? Onset of chronic condition? • Hospitalizations: Date and reason for hospitalization, history of surgery, length of stay, complications after hospitalization? • Unintentional injuries: Falls, nature of injury, age of child when injury occurred, problems after injury? Motor vehicle, bicycle, scooter/skateboard, or pedestrian-related injuries? • Intentional injuries: History of family violence, physical abuse, or intimate partner violence? Child interview should include the following questions: Has anyone hurt you? Have you felt afraid someone would harm you? Is there any bullying or verbal abuse from family members or during school, after-school programs, or childcare? • Immunization: Review immunization dates and current status including status of annual flu vaccine; ask parent/caregiver about reactions to vaccines; date of last TB skin testing and result? If under-immunized, reasons for withholding vaccines or parental concerns about vaccine safety? • Allergies: Allergic to prescription medications or antibiotics; reaction to over-the-counter (OTC) medications? Any food allergies noted? What type of reaction occurred? Severity of the reaction? Was an epinephrine pen (EpiPen) recommended? Reaction to insect bites or bee stings? Pets in home? Environmental triggers? • Medications: Is child taking vitamins, fluoride, or medications regularly? Type of medication? Use of OTC medications? Use of herbs or natural or homeopathic medicines? Cultural healing practices? • Laboratory tests: Review of newborn screening results? Result of newborn hearing screening? Hemoglobin or hematocrit screening for anemia? Lead screening? Tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) screening? • Obtain a history of the infant feeding pattern. Exclusively breastfeeding? Formula feeding? Feeding both breast milk and formula? How often and quantity of formula daily? • Obtain a 24-hour dietary recall during every early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescent encounter. (See later on age-specific content on nutrition and feeding.) • Is there a usual time daily when the family has a common meal? Are there usual family eating patterns? How often does the family eat together at a meal? Who does the food shopping? How often are meals prepared at home? Daily or number of times per week? Number of fast food meals per week? • Vegetarian or vegan diet in family? Are there any special cultural or religious food preferences? • Does the family participate in any supplemental food programs? WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) or SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program)? • Infancy: Stooling pattern, frequency, and consistency? • Early childhood (1 year to 4 years of age): Stooling pattern and frequency, plans for toilet training; resistance to toilet training, difficulties with bowel or bladder control; age bowel and bladder control attained? • Middle childhood (5 to 10 years of age): Daytime or nighttime wetting? Soiling or difficulty with bowel control? Parental attitudes toward wetting incidents? History of encopresis or enuresis? History of constipation or diarrhea? • Sleep patterns and amount of sleep day and night for infants and young children? Bedtime routines? Regular bedtime? Hours of sleep nightly? Where does the child sleep? Co-sleeping until what age? Always sleeps in same household? Concerns about nightmares, night terrors, night waking, somnambulism (sleepwalking)?

Comprehensive information gathering

The genetic family history

SC

Some concerns

“Do you have any (some) concerns about diseases or conditions that run in the family?”

R

Reproduction

“Have there been any problems with pregnancy, infertility, or birth defects in your family?”

E

Early disease, death, or disability

“Have any members of your family died or become sick at an early age?”

E

Ethnicity

“How would you describe your ethnicity?” or “Where were your parents born?”

N

Nongenetic

“Are there any other risk factors or nonmedical conditions that run in your family?”

Family-centered history

Family, cultural, racial, and ethnic considerations

Components of information gathering

Information gathering of subjective data

Present concern

Prenatal and birth history

Prenatal history

Birth and neonatal history

Past medical history

Activities of daily living

Nutrition and feeding

Stooling and elimination patterns

Sleep

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Comprehensive information gathering

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue