Chapter 675 Common Fractures

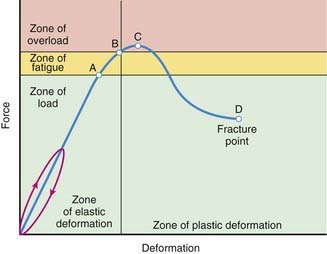

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability in children >1 yr of age. Several factors make fractures of the immature skeleton different from those involving the mature skeleton. The anatomy, biomechanics, and physiology of the pediatric skeletal system are different from those of adults. This results in different fracture patterns (Fig. 675-1), diagnostic challenges, and management techniques specific to children to preserve growth and function.

675.1 Unique Characteristics of Pediatric Fractures

Fracture Remodeling

Remodeling is the 3rd and final phase in biology of fracture healing, preceded by the inflammatory and reparative phases. This occurs from a combination of appositional bone deposition on the concavity of deformity, resorption on the convexity, and asymmetric physeal growth. Thus, reduction accuracy is somewhat less important than it is in adults (Fig. 675-2). The 3 major factors that have a bearing on the potential for angular correction are skeletal age, distance to the joint, and orientation to the joint axis. The rotational deformity and angular deformity not in the axis of the joint motion are less likely to remodel. The amount of remaining growth provides the basis for remodeling; younger children have greater remodeling potential. Fractures adjacent to a physis undergo the greatest amount of remodeling, provided that the deformity is in the plane of the axis of motion for that joint. The fractures away from the elbow and closer to the knee joint have greater potential to remodel because this physis provides maximal growth to the bone. One can expect remodeling to occur over the next several months following injury throughout skeletal maturity. Skeletal maturity is reached in girls between 13 and 15 yr and in boys between 14 and 16 yr of age.

Progressive Deformity

Injuries to the physes can be complicated by progressive deformities with growth. The most common cause is complete or partial closure of the growth plate. As a consequence, angular deformity, shortening, or both, can occur. The partial arrest may be peripheral, central, or combined. The magnitude of deformity depends on the physis involved and the amount of growth remaining. CT and MRI are important for assessing partial arrests and formulating treatment (Fig. 675-3).

Beaty JH, Kasser JR, editors. Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures in children, ed 5, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 2001.

Flynn JM, Kolze EA. Upper extremity injuries. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopaedics: core knowledge in orthopaedics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:47-84.

Flynn JM, Nagda S. Upper extremity injuries. In: Dormans JP, editor. The requisites in pediatrics: pediatric orthopaedics and sports medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:21-48.

Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, editors. Skeletal trauma in children, ed 3, vol 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Olney RC, Mazur JM, Pike LM, et al. Healthy children with frequent fractures: how much evaluation is needed? Pediatrics. 2008;121:890-897.

Overly F, Steele DW. Common pediatric fractures and dislocations. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2002;3:106-117.

Poolman RW. Adjunctive non-invasive ways of healing bone fractures. BMJ. 2009;338:611-612.

Salter RB, Harris WR. Injuries involving the epiphyseal plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:587-622.

Thompson GH, Haber LL. Upper extremity fractures in the pediatric patients. In: Fitzgerald RHJr, Kaufer H, Malkani A, editors. Orthopaedics. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:484-494.

675.2 Pediatric Fracture Patterns

Plastic Deformation

Plastic deformation is unique to children. It is most commonly seen in the ulna and occasionally the fibula. The fracture results from a force that produces microscopic failure on the tensile side of bone and does not propagate to the concave side (Fig. 675-4). The concave side of bone also shows evidence of microscopic failure in compression. The bone is angulated beyond its elastic limit, but the energy is insufficient to produce a fracture. Thus, no fracture line is visible radiographically (Fig. 675-5). The plastic deformation is permanent, and a bend in the ulna of <20 degrees in a 4 yr old child is expected to correct with growth.

Buckle or Torus Fracture

A compression failure of bone usually occurs at the junction of the metaphysis and diaphysis, especially in the distal radius (Fig. 675-6). This injury is referred to as a torus fracture because of its similarity to the raised band around the base of a classic Greek column. They are inherently stable and heal in 3-4 wk with simple immobilization.

Epiphyseal Fractures

The injuries to the epiphysis involve the growth plate. There is always a potential for deformity to occur, and hence long-term observation is necessary. The distal radial physis is the most commonly injured physis. Salter and Harris (SH) classified epiphyseal injuries into 5 groups (Table 675-1 and Fig. 675-7). This classification helps to predict the outcome of the injury and offers guidelines in formulating treatment. SH type I and II fractures usually can be managed by closed reduction techniques and do not require perfect alignment, because they tend to remodel with growth. SH type II fractures of the distal femoral epiphysis need anatomic reduction. The SH type III and IV epiphyseal fractures involve the articular surface and require anatomic alignment to prevent any step off and realign the growth cells of the physis. SH type V fractures are usually not diagnosed initially. They manifest in the future with growth disturbance. Other injuries to the epiphysis are avulsion injuries of the tibial spine and muscle attachments to the pelvis. Osteochondral fractures are also defined as physeal injuries that do not involve the growth plate.

Table 675-1 SALTER-HARRIS CLASSIFICATION

| SALTER-HARRIS TYPE |

|---|