Clinical Trials Involving Children: History, Rationale, Regulatory Framework, and Technical Considerations

Steven Hirschfeld

Brief History of Research Involving Children

Children have been utilized to test new therapies for thousands of years, but prospective clinical investigations to test hypotheses were a development of the 18th century. While living in Constantinople in 1718, Lady Mary Montague, daughter of the Duke of Kinston, observed the Turkish procedure of inoculation against smallpox and had her 6-year-old son inoculated. Upon her return to London, she requested a surgeon to inoculate her 5-year-old daughter. The surgeon used a thread soaked in pustular secretions bound to the skin. This technique was replaced by scarring with a lance tip dipped in pus. The resulting plaque was then covered until it healed, and experimental research in pediatric preventive medicine began in Europe (1).

The American clergymen Cotton Mather also became interested in the procedure after hearing from the slave Onesimus about a practice of using fluid from a patient with mild smallpox to inoculate uninfected people in Africa. Subsequently, he read about the European experience in his correspondence with members of the Royal Society of London. An outbreak of smallpox in Boston in 1721, despite efforts at quarantining the index case, provided an opportunity to experiment. Mather persuaded Boston physician Zabdiel Boylston to proceed with what may have been the first clinical trial in North America. Boylston inoculated his 6-year-old son by lancing the skin and applying to it 9- to 14-day-old pustular material from a smallpox patient, then wrapped the skin in a cabbage leaf. Subsequently, he inoculated 280 people, including 65 children. Unfortunately, six of the adults, although none of the children, subsequently died, with a case fatality rate of approximately 2%. Despite the fact that the smallpox fatality rate for the general population in Boston was 14%, a great controversy about the value of inoculation followed, including the hurling of a bomb into Rev. Mather’s home. Fortunately, the explosive did not detonate, but the practice of inoculation did not become public policy (2).

Experimental immunotherapy evolved further with the work of Edward Jenner in England. In 1796, Jenner injected James Phipps, an 8-year-old boy, with extract from pustules from the hand of Sarah Nelmes, a milkmaid. Jenner had been told by milkmaids that cowpox protected them against smallpox. The word vaccination is derived from the Latin word for cow-vaccine. Jenner examined his patient every day, and then 2 weeks after the cowpox injection; Jenner applied a challenge of smallpox extract and found that the boy was protected. He expanded his study from the initial child to “a number” of others ranging in age from 11 months to 8 years. None of the children became ill. Over the course of the next 50 years, vaccination became compulsory in some areas of England (3).

During the 19th century, children’s hospitals were established in Europe and the United States in cities including Paris, Vienna, London, Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. Concurrently, pediatrics became an academic specialty, and textbooks were published. Ludwig Friedrich Meissner of Leipzig, Germany, published a survey of texts and monographs pertaining to pediatric medicine, in 1826 noting that prior to 1,775 there were 200 publications and subsequently there were at least almost 7,000 (1).

In 1828, Charles-Michel Billard of the Hospice des Infants Trouvts in Paris published a revolutionary treatise classifying pediatric diseases on the basis of pathology rather than symptoms. In addition, he included a catalogue of height, weight, and vital signs (4). This was followed by surveys by Quetelet in Belgium and Chadwick in England on growth rates of children showing that lower socioeconomic class was associated with less growth, most probably due to nutritional deficiencies (5,6). Comparative pharmacology began about the middle of the 19th century.

In 1834, the first periodical devoted entirely to the care of children, Aizalekteiz iiber Kinderkrankheiten (Annals of Diseases of Children), was published in Stuttgart; it ceased publication in 1837 after publishing 12 volumes. Over the course of the following decades, many journals appeared in several countries as academic societies and publishing houses developed interest in the field of pediatric research (7).

In 1847, John Snow began to administer anesthesia with ether to children aged 4 through 16 years. He also experimented with chloroform and by 1857 had successfully anesthetized hundreds of children, including 186 infants under the age of 1 year. He first described differences in metabolism between adults and children, noting that the effects of chloroform were more quickly produced and also subsided more quickly in children, explaining the observation in terms of the quicker breathing and circulation in pediatric patients (1).

Frederik Theodor Berg was appointed the first European professor of pediatrics at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1845. In 1858, he resigned from the post to become Director of the Central Bureau of Statistics. In that capacity, he expanded the bureau’s data banks to include not only population, but also welfare, agricultural, and industrial data. He founded a statistical journal in 1869, and in the same year, utilizing parish records, he published a paper analyzing infant mortality rates in Sweden (8).

The first course in the United States at an academic institution devoted to pediatrics was offered at the Yale College of Medicine in 1813 by Eli Ives (9). In 1860, Abraham Jacobi, an émigré from Germany, was appointed as professor of infantile pathology and therapeutics at the New York Medical College, which may have been the first full academic pediatric appointment in America. A pediatric clinic with the first use of bedside teaching was founded in 1862 (10).

The first institution for sick children in the United States was founded in 1855 in Philadelphia. Boston and New York followed in 1869, and the District of Columbia in 1871. By 1880, Jacobi had been instrumental in the establishment of several hospitals for children in the United States—Chicago, San Francisco, St Louis, and Cincinnati—so that by 1895 there were 26 children’s hospitals in this country. In 1868, Jacobi wrote an article on croup in the first issue of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children, published by the American Medical Association. The first American journal dedicated totally to pediatric research. Archives of Pediatrics began publication in 1884.

In 1880, Jacobi organized the pediatric section of the American Medical Association (AMA) and in 1885, he became President of the New York Academy of Medicine. In 1888, he became a founding member of the American Pediatric Society, which limited membership to 110. The society published its Transactions, which, for the first third of the 20th century, was the major American journal devoted to pediatric research. Jacobi was among the first to recognize the potential of using government resources to advance clinical science. He is credited with persuading the US Congress to appropriate the funds for the first printing of Index Medicus, compiled by his friend John Shaw Billings (11).

Transition into the Twentieth Century and the Beginning of Ethical Concerns and Regulation

Claude Bernard wrote in 1865, “It is our duty and our right to perform experiments on man whenever it can save his life, cure him, or give him some personal benefit” (12). This statement has been interpreted that ethically only studies that provide direct benefit to the participants should be undertaken, but the principle had no legal authority. The question of prior permission to participate was not addressed.

The last decades of the 19th century saw further experimentation in immunotherapy for the treatment of infectious diseases, with many of the major advances resulting from studies on children. In 1885, Pasteur injected 9-year-old Joseph Meister of Alsace, who had been bitten by a rabid dog, with extract of rabbit spinal cord from a rabbit that had died of rabies 2 weeks before. Thirteen inoculations were given daily with the last an extract from a rabid dog. The boy recovered and a second shepherd boy was similarly cured (13).

In 1892, an immunologic approach to reduce transmission of venereal disease was attempted in a study by Albert Neisser, professor of dermatology and syphilis in Breslau and discoverer of the organism responsible for gonorrhea. He subcutaneously and intravenously injected eight women and girls, the youngest being 10 years old, with cell-free extract of syphilis in an attempt to stimulate an immune response.

Subsequently, four of the women became infected, leading to the speculation that the cause of their illness could have been Neisser and his experiment, and a subsequent public scandal followed (14). The debate continued primarily in the press for several years until December 19, 1900, when the Prussian Ministry of Education and Medicine issued a policy statement about human experimentation. The proclamation stated that research may not be performed without the permission of the patient and that research on children was forbidden. It further stated that research should have as its goal the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease.

This was probably the first government edict about human research, and although a potent statement had been made, enforcement powers did not follow (15). The rise of the chemical industry, particularly in Germany, fed the hope of targeting diseases through the administration of manufactured compounds. As an example, the recognition of genital infections as a source of infant morbidity led Karl Sigmund Franz Crede in 1884 to use silver nitrate solution to prevent gonorrhea infections of the eyes of the newborn (16,17).

There was a rush to examine the medical (and potential commercial) activity of many newly synthesized products, spurred by Paul Ehrlich’s vision of a “magic bullet” and a permissive social climate. In 1902, the psychiatrist Albert Moll published a monograph, Aertzliche Ethik (Medical

Ethics), in which he catalogued some 600 publications of medical experiments where, he argued, there was no possible benefit to the subject. Moll criticized not only the dangers of the experiments, but the lack of advantage to the patient (18,19). Despite the Prussian edict and Moll’s book, however, there would be no translation of patient protection into public policy for another third of a century.

Ethics), in which he catalogued some 600 publications of medical experiments where, he argued, there was no possible benefit to the subject. Moll criticized not only the dangers of the experiments, but the lack of advantage to the patient (18,19). Despite the Prussian edict and Moll’s book, however, there would be no translation of patient protection into public policy for another third of a century.

Evolution of Ethical Principles and Their Application to Research

Health crises involving children have played a major role in the evolution of food and drug law in the United States. The first major domestic controls occurred early in the 20th century, following more than 100 attempts in the 19th century to pass federal legislation, regulating the manufacture and sale of foods and drugs. In the autumn of 1901 in St Louis, more than a dozen children died of tetanus after receiving diphtheria antitoxin that had been recovered from a tetanus-infected horse. Subsequently, another 100 cases of tetanus were reported, including the deaths of nine more children. This led to the passage of the Biologics Control Act of 1902, which called for the licensing, labeling, and supervision of biological products intended for humans (20).

In the autumn of 1905, Collier’s Weekly published an exposé of fraud in the manufacture and sale of patent medicines, citing cases of infants who died following administration of syrup that contained morphine that was intended to treat colic. Although concern was widespread, public documentation of specific cases of death or morbidity due to commercial drugs was lacking due to contract clauses on publications by drug manufacturers threatening to cancel advertisements if legislation regulating drug marketing was passed. Nevertheless, through the efforts of a coalition of chemists, women’s clubs, state officials, civic organizations, and writers, in June 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the first Pure Food and Drug Act into law. The Act established the need for product labels, prohibited interstate commerce in adulterated or misbranded drugs, and established the need to maintain standards (20). There was, however, a provision in the Act that permitted deviation from the standards if they were stated on the label. Enforcement was to be by the courts.

This led to the case of US versus Johnson in 1911, in which a majority of the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the defendant, the manufacturer of Dr. Johnson’s Mild Combination Treatment for Cancer, this claimed as its ingredients a mixture of substances with the names like Cancerine tablets, Antiseptic tablets, Blood purifier, Special No. 4, Cancerine No. 17, and Cancerine No. 1. The Court stated that prosecution was to be limited to false and misleading statements about the ingredients or the identity of a product and was not intended to extend to false therapeutic claims (21). In an effort to address the gap, the 1912 Sherley Amendment to the Pure Food and Drug Act stated that false therapeutic claims could be prosecuted, but only if intent to defraud could be proven in court (22). The rising political prominence of pediatrics led to the first White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children in 1909. Based on a recommendation from the Conference, the United States Children’s Bureau was established by Congress in 1912 to coordinate health care policy (23).

World War I had multiple aftereffects, including recognition of the poor physical condition of many of the young men recruited to serve in the armed forces. A political response was the Sheppard-Towner bill in 1921 to provide funding for the health care of poor mothers and infants and extend health supervision from infancy to preschool children (24). The question of the role of government and how much support it should provide for health care and children’s issues was debated for much of the 20th century, primarily on philosophical and political grounds.

The next major change in regulations occurred in 1927 when the Federal Caustic Poisons Act was passed in an effort to protect children from lye and other dangerous chemicals by requiring labeling with warnings and antidotes.

The American Medical Association was not sheltered from this discussion and at the 1928 meeting there was planning for a society that would be open to any physician trained in pediatrics. Two years later a schism occurred within the AMA on the issue of government support for clinics to treat infants and children with the goal of reducing mortality. A group of pediatricians withdrew and formed a new organization, the American Academy of Pediatrics (25).

In 1930, the US Congress established the National Institutes of Health by renaming the US Hygiene Laboratory in Washington, DC (26). In addition the Food, Drug and Insecticide Administration was established as an enforcement agency. The name was shortened in 1930 to the Food and Drug Administration. Legislation to revise the 1906 Food and Drug Act was proposed in 1933, but became mired in Congress (20).

In 1931, the German Ministry of the Interior issued the first guidelines published for the conduct of research on children. These were part of general guidelines for the conduct of clinical research that were issued in response to allegations by the press and members of the national legislature of questionable and even unethical conduct by physicians. The guidelines were the initial governmental statement of requirements for the ethical conduct of clinical research, which are found in subsequent statements such as the Helsinki Declaration.

The general principles were the primary obligation and duty of the experimenter to protect the subject, the need for informed consent in all circumstances, the principle of preclinical testing in animals prior to human use, and the principle of accurate publication of findings. An experimental compound was defined as any intervention that did not contribute directly to the treatment of an individual patient. No mention is made of peer review in either the experimental or publication process, although the Berlin medical board, which earlier in the century had issued its own recommendations on protection of research subjects, had proposed a regulatory oversight body. This proposal was not incorporated into the final guidelines.

The German guidelines contained two sentences specifically about children: “Application of the new treatment must be considered particularly carefully if it involves infants or

adolescents of less than 18 years” and “Experimentation on infants or persons of less than 18 years is forbidden even if it will only expose them to a very slight danger” (27).

adolescents of less than 18 years” and “Experimentation on infants or persons of less than 18 years is forbidden even if it will only expose them to a very slight danger” (27).

In September 1937, the Samuel E. Massengill Pharmaceutical Company in St Louis marketed the newly discovered antibiotic sulfanilamide as a 10% solution, substituting 72% diethylene glycol for the usual solute of ethanol and sweetening it with sugar and raspberry syrup. The resulting elixir killed more than 100 people, including many children, due to glycol-induced renal failure and resulted in the suicide of the chemist who made it. The product was only labeled as an elixir, which implied ethyl alcohol and did not state the full list of ingredients, and thus the company was charged with misbranding. The absence of an applicable law meant that there was no culpability for the deaths.

This tragedy led to the passage of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt in June 1938. The Act gave authority to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to require that safety is established before marketing, required disclosure of all active ingredients, required directions for use and warnings about misuse unless the product was sold by prescription, allowed federal inspections of manufacturing facilities, established procedures for the formal review of applications for marketing, explicitly prohibited false claims, and extended the scope of the regulation to cosmetics and devices. There were no provisions for premarketing review, and only those products that were to be sold for interstate commerce were covered. All applications were automatically approved if the FDA did not act within 60 days. The regulation of advertising of therapeutics was assigned to the Federal Trade Commission (28).

International recognition of the need to protect participants in clinical experiments surfaced during the Nuremberg military tribunals in 1946. Evidence was given that up to 200 German doctors had performed experiments with prisoners of war and civilians, which had no protections for the participants and caused harm without any prospect of benefit. The subsequent court proceedings led to the development of the Nuremberg Code, which established international standards for the treatment of one human by another. The guiding principle was that, “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.” This statement has been widely interpreted as precluding research on children, although the Nuremberg Code is silent on the specific subject of pediatric research (29).

In 1962, the tragedy of the births of malformed children, primarily in Europe and Canada due to the effects of thalidomide taken as a sedative by their mothers while pregnant resulted in part in Congress passing the Kefauver-Harris amendment to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.

This amendment added an important new facet—the requirement that a product demonstrates efficacy prior to approval of a marketing claim. Additional provisions in the amendment were the need to establish good manufacturing practice (GMP) and maintain production records, the requirement to file an application with the FDA prior to clinical testing (Investigational New Drug application, or IND), an increase in the time for FDA marketing authorization review from 60 to 180 days, the transferral of regulatory authority for drug advertising to the FDA, and withdrawal of approval if new evidence indicated lack of safety or effectiveness (30). The addition of an efficacy requirement prompted a retrospective study by the National Academy of Sciences of FDA approvals between 1938 and 1962, which showed that 40% of the drugs were not effective (31). The new aspect in analysis of product use by adding an efficacy requirement was that benefit and risk could be assessed and acceptable ratios of risk to benefit determined for the intended use at the prescribed dose.

To summarize, the three principles of regulation—labeling, safety, and efficacy—were formalized during the first two-thirds of the 20th century. Formal guidelines for the protection of participants in research and children, in particular, are a product of the last third of the 20th century.

As a point of reference, protection for animals goes back to the 19th century. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Cruelty to Animals Act became law in 1876 (32). In 1960, Louis G. Welt, of the Department of Medicine at Yale University, sent a questionnaire regarding practices for clinical research to university departments of medicine. Sixty-six replied, of which 24 (36%) either already had or were in favor of establishing a committee to review studies involving human experimentation (33). In 1962 the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom made a statement in its annual report that drew a distinction between research interventions intended to be of direct benefit to the subject of the research and those that are not so intended. These two categories of research were referred to as “therapeutic” and “nontherapeutic,” respectively. The report went on to state that, “In the strict view of the law, parents and guardians of minors cannot give consent on their behalf to any procedures which are of no particular benefit to them and which may carry some risk of harm.” This statement has regularly been interpreted as placing a complete embargo on nontherapeutic research on children. A follow-up report in 1963 addressed some of the perceived legal and ethical problems in clinical research.

The World Medical Association adopted in 1964 the Declaration of Helsinki: Recommendations Guiding Medical Doctors in Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. The document made a distinction between therapeutic and nontherapeutic research, and stated that protocols, independent review of the proposed research, and informed consent should be part of the protection of participants in research. Third-party consent for a participant unable to consent was described, thus offering an approach to pediatric research (34).

Henry Beecher, professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, published an article titled “Ethics and clinical research” in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1966 (35). He drew attention to 22 reports that contained clinical research with a variety of ethical problems, most of which put patients at considerable risk. One of these was the Willowbrook study in New York, which exposed institutionalized children to serum infected with hepatitis. The study was

performed with institutional approval, and parents gave permission. The rationale was that hepatitis was so prevalent that the children were likely to become infected and that it was scientifically important to study the early phases of the infectious process.

performed with institutional approval, and parents gave permission. The rationale was that hepatitis was so prevalent that the children were likely to become infected and that it was scientifically important to study the early phases of the infectious process.

The Willowbrook approach of using institutionalized children as experimental subjects was not unprecedented. Other studies with institutionalized children in Massachusetts during the 1950s exposed children to radioactive compounds, in one case to study mineral absorption and in another case to study the protective effect of nonradioactive iodine in blocking radioactive iodine in the event of a nuclear explosion. Both studies had federal funding, and the former study had additional funding from the Quaker Oats Company because one of the study questions was to examine the effect of cereal composition on mineral absorption (36).

In 1966, the Surgeon General of the United States, Dr. William H. Stewart, issued a memo based on recommendations by his predecessor, Dr. Luther Terry, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) director, Dr. James Shannon, requiring institutions accepting federal funds to certify to establish independent review of research projects before they were started. In addition, institutions had to provide the relevant federal funding agency assurance that procedures were in place for consent and review.

In December 1966, the policy was expanded to include behavioral as well as medical research (37). In 1967, the Public Health Service required that intramural research, including that conducted at NIH, abides by similar requirements. Even institutions with existing review committees had to improve their procedures to comply with the new regulations (38).

Also in 1967, the UK Royal College of Physicians Committee on the Supervision of the Ethics of Clinical Investigation in Institutions published a first report recommending that every hospital or institution in which clinical research was undertaken has a research committee that should satisfy itself of the ethics of all proposed investigations. The proposed research committees, with at least one lay member, should be established in every region to review the ethics of proposed investigation, and by law they should be responsible to the General Medical Council (39). In the same year, M. H. Pappworth published Human Guinea Pigs, which detailed several hundred reports of questionable ethics in human experimentation (40).

In 1973 in Great Britain, the chief medical officer of the Department of Health and Social Security requested the Royal College of Physicians Committee to again make a recommendation. The subsequent committee report reflected a shift in attitude. It stated,

If advances in medical treatment are to continue, so must clinical research investigation. It is in this light, therefore that it is recommended that clinical research investigations of children or mentally handicapped adults which is not of direct benefit to the patients should be conducted, only when the procedures entail negligible risk or discomfort and subject to the provisions of any common and statute law prevailing at the time. The parent or guardian should be consulted and his agreement recorded.

This revision appears to suggest that it is permissible to conduct nontherapeutic research on children, provided this is perceived to be of negligible risk (41). In 1974, the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare issued regulations requiring institutions that receive federal funds for research to establish institutional review boards and described procedures and criteria for informed consent (42).

Also in 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act. All federally funded clinical research proposals as well as the adequacy of informed consent had to be reviewed by an institutional review board with oversight and enforcement dependent on the particular federal funding agency, meaning there was no global oversight of federally funded research (43).

The National Research Act established a National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Medical and Behavioral Research. The National Commission had a mandate to develop ethical guidelines for the conduct of research on human subjects, in particular children, and to make recommendations to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. To prepare the report, the National Commission, over the next several years, held public hearings, commissioned papers and other reports, commissioned a survey of the practice of more than 400 investigators engaged in pediatric research, and convened a national conference to ensure that the views of various constituencies were heard (44).

When the UK Department of Health and Social Security issued a circular titled Supervision of the Ethics of Clinical Research Investigations and Fetal Research in 1975, it drew attention to this point, stating, “(one) ought not to infer from this recommendation that the fact that consent has been given by the parent or guardian and that the risk involved is considered negligible will be sufficient to bring such clinical research investigation within the law as it stands” (45). The British chief medical officer wrote in another publication that it was not legitimate to perform an experiment on a child that was not in the child’s interests.

The 1975, revision of the Declaration of Helsinki addresses this point by stating, “the potential benefits, hazards and discomfort of a new method should be weighed against the advantage of the best current diagnostic and therapeutic methods.” It provides no clear guidance on the subject of nontherapeutic research on children or any other potential subject deemed legally incompetent. The final statement of the Declaration concerning nontherapeutic research states, “In research on man, the interest of science and society should never take precedence over considerations related to the well-being of the subject” (46).

The US National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was established in 1974 and began publishing reports beginning in 1976 on research involving prisoners and in 1977 on research involving children (44). The latter report contains an analysis of law as it applies to research of children and considerable discussion of the ethical bases of various viewpoints.

The conclusions were that research involving children was important for the health of all children and that such research could be conducted ethically within the general conditions outlined in documents such as the Helsinki Declaration. The rationale for pediatric research was based on two factors: (a) children are different than adults

and animals in general, and some diseases only occur in children, and (b) the risk of harm from treatments and practices is increased without research. Part of the mission was to develop guidelines. These included a determination by an institutional ethical review board that the proposed study is scientifically sound and significant; that appropriate studies must be conducted first on animals, subsequently in adult humans, and then on older children before involving infants; and that the risks must be minimized by using the safest method consistent with sound research design and by using procedures performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes whenever feasible.

and animals in general, and some diseases only occur in children, and (b) the risk of harm from treatments and practices is increased without research. Part of the mission was to develop guidelines. These included a determination by an institutional ethical review board that the proposed study is scientifically sound and significant; that appropriate studies must be conducted first on animals, subsequently in adult humans, and then on older children before involving infants; and that the risks must be minimized by using the safest method consistent with sound research design and by using procedures performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes whenever feasible.

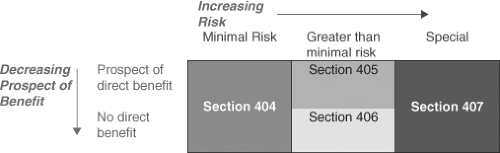

Figure 7.1. Risk categories and applicable sections of Subpart D, 45 CFR 46, the subpart of the common rule of the federal regulations governing federally funded research that applies to children. |

Parents must provide permission for children to participate in research and the child, when feasible, should provide assent. Assent was considered feasible for a normal child at 7 years of age. The Commission report, in an innovative approach, categorized risk and made the following recommendations:

Research not involving greater than minimal risk might be conducted on children subject to permission obtained from parents.

Research greater than minimal risk might be conducted if it held out the prospect of direct benefit to the subject.

Research not holding the prospect of benefit to the subject might be conducted so long as the risk involved was no more than a minor increase over minimal.

An additional category for research that was not included in the previous categories is research that carries no prospect of direct benefit to the subject, but carries a risk greater than a small increase over minimal. Such research could be carried out provided it was approved by a national ethics advisory board and was open to public review and comment.

The Commission also recommended that adolescents could have the requirement for parental permission waived in particular circumstances. The Commission published a report in 1978 on institutional review boards, and in 1979 the Belmont Report (named after the donor of the conference room where the Commission met) reviewed the Commission’s findings and outlined the ethical basis for clinical research (47,48). These can be summarized in the following three principles:

Respect for the personal dignity and autonomy of individuals, with special protections for those with diminished autonomy.

Beneficence to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

Justice to distribute fairly and equitably the benefits and burdens of research.

The recommendations of the Commission were adopted in June 1983 as federal regulations that apply to all federally funded research (45 CFR 46), with only some minimal changes, for example, excluding the waivers for parental permission for adolescents. Subpart A applies to all research participants, Subpart B applies to research enrolling fetuses and pregnant women, Subpart C applies to research with prisoners, and Subpart D applies to research with children. Sections within Subpart D describe the risk categories and are shown in Figure 7.1 (49).

In 1978, the British Paediatric Association set up a working party on the ethics of research on children. Their report was published in 1980 as guidelines to aid ethical committees considering research involving children. The guidelines were based on the following four premises:

Research involving children is important for the benefit of all children and should be supported and encouraged and conducted in an ethical manner.

Research should never be done on children if the same investigation could be done on adults.

Research that involves a child and is of no benefit to that child (nontherapeutic research) is not necessarily unethical or illegal. This statement had no evidence presented to support the premise. Reference was made without discussion to a single paper that argued that courts were likely to take a more lenient view of the practice of nontherapeutic research on children than had been supposed.

The degree of benefit resulting from research should be assessed in relation to the risk of disturbance, discomfort, or pain—in other words, the risk-to-benefit ratio.

The rest of the report is a broader discussion of the concept of risk-to-benefit ratio. It states, for example, that more than negligible risk of nontherapeutic research in children may be justified provided that the anticipated benefits are sufficiently great. In examples, the report gives circumstances where, for instance, a renal biopsy might be taken during abdominal surgery or nontherapeutic blood sampling including repeated glucose tolerance tests in diabetic children may be done to answer important research questions.

The key concept is the definition of negligible risk, which is “risk of less than that run in everyday life.” The key components to be considered in assessing risk are the degree and the probability. The report stated that both degree and probability are part of the definition (50). Another aspect of the British Paediatric Association guideline is any absence of any specific mention of the

supremacy of the research subject’s interest over the interest of others. It instead places an emphasis on risk-benefit analysis.

supremacy of the research subject’s interest over the interest of others. It instead places an emphasis on risk-benefit analysis.

In 1980, the British Medical Association issued a handbook of medical ethics. It has a brief discussion of research in children. There is no distinction between therapeutic and nontherapeutic research. It does state, however, that adequate background information must be provided to the local ethics committee to judge the scientific merit of the proposal. Although it may be argued that research projects must have scientific merit to be considered ethical, it is unclear that research ethics committees are the most competent forums to evaluate the issue.

The handbook also states that “The investigator should indicate the method he will use to obtain consent, i.e., for the parents or the general practitioner or consultant in charge of the case.” This implies that there are occasions when an investigator may obtain consent from another doctor for a research procedure to be carried out on a child without any attempt to obtain either the child’s assent or the parent’s’ consent. There is no legal basis to this in British law. Consent given by another physician would not carry any weight in a court of law. It is more likely to result in a charge of assault (51).

Tyson et al. (52) published a study in 1983 that evaluated the quality of perinatal research. The object of the investigation was to determine the quality of the studies because the treatment methods recommended were widely and rapidly incorporated into clinical practice after publication in a respected obstetric and pediatrics journal. They found that many of the studies failed to meet the criteria for quality perinatal therapeutic research, as shown in Table 7.1.

The report of the working group on Ethics of Clinical Research Investigations on Children by the Institute of Medical Ethics in Great Britain 1986 made a number of detailed recommendations including comments on the effects on the emotions and behavior of children who participate in research and encouragement to not separate children from their parents during procedures (32).

Lack of Benefits to Children of Pharmaceutical Industry Research

The US Federal government has been systematically supporting clinical trials with children since the 1950s. Early studies on childhood leukemia were sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, on rheumatic heart disease by the National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute, on retrolental fibroplasias by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, on diabetic retinopathy by the National Eye Institute, on diabetes by the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, on extra cranial to intracranial arterial anastomosis (a clinical trial) by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, and on hereditary angioedema (a clinical trial) by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (53). An NIH institute dedicated to pediatric investigation was founded in 1960, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The first director was Dr. Robert Aldrich (54).

As noted previously, in 1962, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act was amended to include efficacy data in the FDA approval process and in the approved product package insert. Despite the growing interest in pediatric research, the majority of medications used in children were not studied in children. In 1968, Dr. Harry Shirkey coined the term “therapeutic orphan” to refer to the situation in which sick children were deprived of access to medications because the drugs had not been adequately tested in children (55).

Table 7.1 Summary of Review of 88 Therapeutic Trials | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1972 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Charles Edwards, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, stated

that a large percentage of the drugs used in sick infants and children are prescribed on empirical grounds (56). In 1973, a report from the National Academy of Sciences emphasized the different nature of the response of an immature organ to pharmacologic agents and suggested that innovative investigative programs were needed to supply information on the use of pharmacologic agents in the pediatric population. Among the reasons cited was that children are different from adults in the process of drug disposition and receptor sensitivity. As an example, the plasma concentrations of the drug theophylline change with the age of the patient.

that a large percentage of the drugs used in sick infants and children are prescribed on empirical grounds (56). In 1973, a report from the National Academy of Sciences emphasized the different nature of the response of an immature organ to pharmacologic agents and suggested that innovative investigative programs were needed to supply information on the use of pharmacologic agents in the pediatric population. Among the reasons cited was that children are different from adults in the process of drug disposition and receptor sensitivity. As an example, the plasma concentrations of the drug theophylline change with the age of the patient.

In 1974, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a report commissioned by the FDA: General Guidelines for the Evaluation of Drugs to Be Approved for Use During Pregnancy and, for the Treatment of Infants and Children (57). In the following year, Dr. John Wilson found that 78% of prescription drugs had a statement in the package insert that the use in infants and children had not been adequately studied or there was no statement and the label was silent on the issue (58).

The FDA adapted the AAP report and in 1977 published it as a guidance document titled General Considerations for the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs in Infants and Children. The major points were an emphasis on anticipating and describing unexpected toxicities in the pediatric population, an expectation that reasonable evidence for efficacy should exist prior to study in infants and children, that only sick children should be enrolled in studies, a preference for active or historical controls over placebo controls, and a recommendation for studying patients in decreasing age order so that experience is gained with older children first (59). Concurrently, the AAP issued Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Studies to Evaluate Drugs in Pediatric Populations (60).

In 1979, the FDA issued a regulation adding a Pediatric Use Subsection to the Product Package Insert Precautions Section (61). The intent was to highlight differences in adverse event profiles and to note whether any pediatric use information existed.

Although not directed exclusively at pediatric patients, an important regulatory change occurred in 1983 with passage of the Orphan Drug Act (62). The Act outlined criteria whereby rare diseases, many of them pediatric, and defined as having a prevalence of less than 200,000 in the United States, could benefit from incentives to develop new therapeutics. The program is administered by the FDA and provides both a longer period of marketing exclusivity (7 years for an “orphan” indication compared to 5 years for the first approved indication of a new molecular entity) and subsidies in the way of grants and technical advice for clinical development. An orphan designation is given to the combination of a rare disease and a product. This allows the same disease to have multiple products qualify for orphan designation and does not restrict a product to only treat an orphan disease. The Orphan Drug Act established the principle of government incentives to promote product development in areas of public health need.

Despite the initiative to encourage pediatric data, in 1988 Dr. Franz Rosa, an FDA epidemiologist, surveyed product labels for drugs that are used in infants and found that only 50% had been formally evaluated. Of these, half had been considered safe and effective and the other half had a caution or risk statement in the product label. Of the 50% that had not been evaluated, 60% had a disclaimer about not being indicated for use in children and 40% had no information (63). An independent survey in 1991 found that, just as in 1975, about 80% of product labels had either limited pediatric dosing information or had a disclaimer for use in children (64).

Federal Pediatric Initiatives

To further encourage pediatric therapeutic development and the inclusion of pediatric information in product package inserts (product labels), in 1994 the FDA revised the Pediatric Use Section of the regulations, adding a subsection (iv) permitting extrapolation of efficacy data if the disease course in adult and pediatric patients was similar (65).

An FDA guidance document issued in 1996 on the Content and Format of Pediatric Use Section noted that extrapolation should be considered, that the effects of the drugs, both beneficial and adverse, in adult and pediatric patients should be described, and that critical literature references should be included. Compliance was voluntary and did not result in an increase in the proportion of products with pediatric labeling (66).

Also in 1995, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs issued a revision of its Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Studies to Evaluate Drugs in Pediatric Populations with detailed discussion of institutional review boards, informed consent, risk and benefit determination, investigator competence. scientific validity and special cases of the dying patient, the newly dead patient, and patients with chronic progressive and potentially fatal diseases (67).

The NICHD established the Pediatric Pharmacology Research Network in 1994 as the first national network for pediatric research, with seven institutions. The network was expanded to 13 institutions in 2001 (68).

As part of the 1997 Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA), an incentive, similar in spirit to the Orphan Drug Act, was added as an option for certain types of products for which pediatric data were submitted to the FDA in response to a written request from the agency.

The incentive was a 6-month extension to existing marketing or patent exclusivity for any product that had the active moiety that was studied in the written request. To qualify for the incentive, a study report must be submitted to the FDA that fairly responds to the terms of the written request.

The results of the submitted studies must be interpretable and informative, but do not need to demonstrate a positive outcome. A negative study can be part of the submission and still contribute to the granting of pediatric exclusivity because the intent is to provide appropriate pediatric information. Existing and newly approved products could qualify with the exception of biologicals, certain antibiotics, and devices (69).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree