CHAPTER 14 Clinical examination and diagnosis

Summary box

Introduction

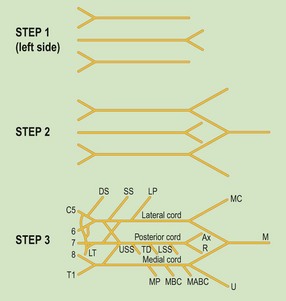

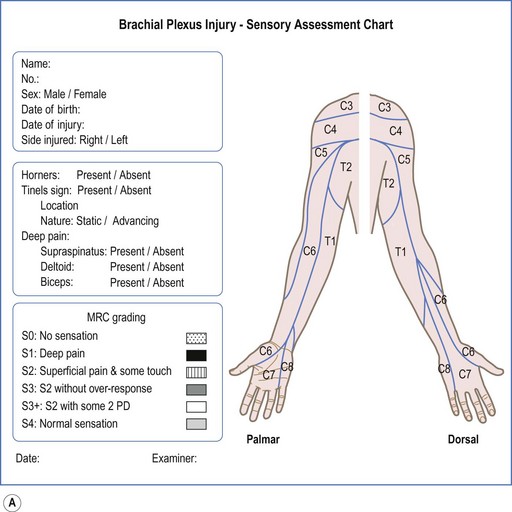

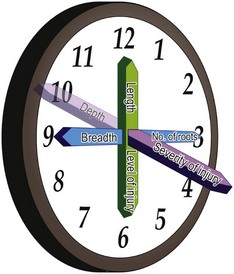

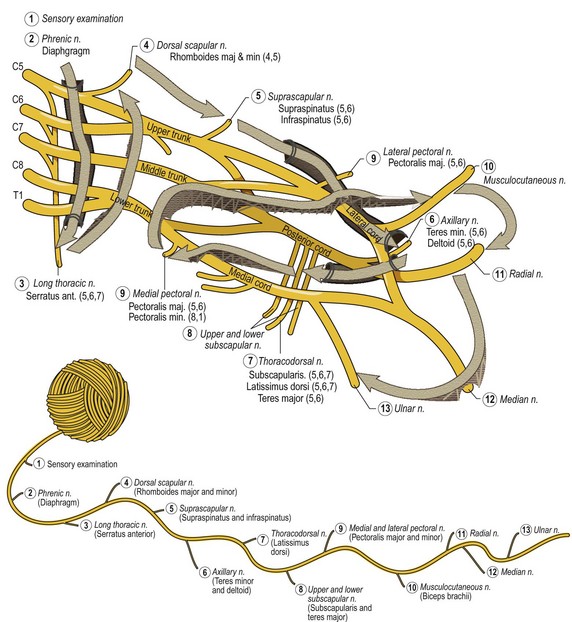

All that is required are three things; a revision of the anatomy of the plexus, revision of the technique of examining specific muscles, and a chart to document the result of the clinical examination. There is no simpler way to revise the anatomy than to read the paper by George Edwards (Figure 14.1).1 Muscle examination has been summarized well in section 4 of Tubiana et al.’s classic book Examination of the hand and wrist.2 Most charts3,4,5 are box based, and although they give valuable information as to the root levels of the muscles affected, they are difficult to use for someone who is not familiar with brachial plexus anatomy. We use a chart based on the branches of the plexus. (Figure 14.2).

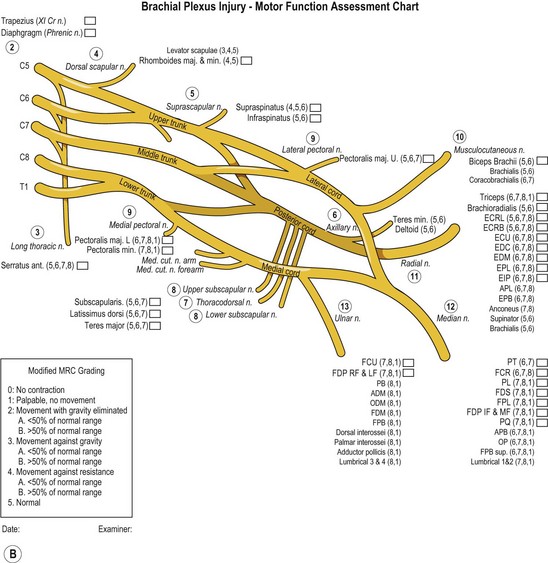

Another concept we have found useful, when trying to describe a brachial plexus injury, is to relate it to the four dimensions of space (Figure 14.3).6 The first dimension to consider is the breadth of the lesion, which indicates the number of roots involved, the extent of the injury. The next dimension is length, which corresponds to the level of injury indicating whether the injury occurred at the roots, trunks or cords. The third dimension is the depth of the lesion, which refers to the severity of the injury, and this is understood in terms of the grades of nerve injury as classified by Sunderland.7 Time, the fourth dimension unmasks the true extent of the injury by allowing the recovery of partially injured roots, and can reveal reconstructive options.

Clinical presentation

Diagnosis

History

There are four main points to be acquired:

The objective of determining the events surrounding the accident is to establish the depth or severity of the injury. In developing nations, motorcycle accidents are the cause of a brachial plexus injury in 82% of cases, as in Songcharoen’s series of 520 cases.12 In developed countries, the causes are varied and sports related injuries are more common. ‘Burners’ or acute traction injuries caused by stretching of the upper plexus roots when tackling or falling affects up to 50% of football players.13 A high speed motorcycle accident on a highway is more likely to cause a severe nerve lesion than a scooter collision with a pedestrian on a city road. The energy transfer in an injured football player would be even less.

The pain that patients feel is neuralgic and is caused by interruption of the nerve. It is commonly described as burning or stabbing and distresses them greatly. Severe pain is often a sign of avulsion.14 Patients can be surprisingly specific about the radiation of this pain, and can even refer it to a dermatomal distribution. This symptom is an accurate indicator of the breadth of the lesion, or the root involvement. A C5/C6 avulsion injury will manifest in neuralgic pain in the lateral aspect of the arm, forearm, and thumb.

Physical examination

Inspection

It is important to understand that a nerve root avulsion does not indicate just the level of the injury, but also the severity. This has profound implications for reconstruction, both in terms of timing and options. Avulsion of the upper roots (C5/C6 and/or C7) is manifested in scapular winging and wasting of the trapezius, whereas avulsion of the lower roots (C8/T1) is revealed by a Horner’s sign. If a patient presents with a flail upper limb, winging of the scapula and a Horner’s sign, it is evident that he has an avulsion injury of all the roots (Figure 14.4 A and B). Another indicator of avulsion is cervical scoliosis, following disruption of the posterior branches of the spinal nerve going to the cervical paravertebral muscles (Figure 14.4B).15 The moisture of the skin can also give useful information about the lesion. Dry skin in an anaesthetic area suggests a post-ganglionic lesion; on the contrary, a normal moist skin suggests a pre-ganglionic lesion. Sliding a plastic pen over the skin of the affected limb and comparing it to the normal side can be used to test sweating function of the skin.16 Other indicators of a severe lesion are associated injuries and scars. Finally, the way the patient is able to cope with the paralysis, take on or off his/her clothes and deal with normal activities is important to note (Video 1: patient coping with ADL’s). The older the lesion, the easier it is to make a complete diagnosis just by inspecting the patient.

Palpation

The examination should always start by testing dermatomes. This is the easiest way to determine the extent of the lesion and gives important and reliable information. The key to remembering the dermatomal map is that the middle finger is supplied by the middle root that is C7. The rest of the map can then be worked out quite logically by working ones way, cranially and caudally. C6 supplies the thumb, C5 the lateral arm and forearm, C8 supplies the little finger and T1, the medial forearm (Figure 14.2A). There are four notes of caution. The medial aspect of the arm is supplied by T2, the inter-costobrachial nerve. The index finger is usually supplied by C7, as donor morbidity from cross C7 transfers has demonstrated.17 Incomplete nerve lesions or lesions affecting C5 may not give complete anesthesia of the dermatome. Over time, adjacent neurotization may blur the edges of the dermatomal territories.

Once the extent of the injury has been determined, the next step is to determine the level of the injury. This is done by muscle examination. The medical research council (MRC) grading has been the standard for assessment of motor power.18 Though it is simple, each MRC grade represents a wide range, and one cannot quantify a difference between muscles in the same grade or an improvement in the same muscle on follow-up.19 We have modified the MRC grade for use in our practice (Figure 14.2B). In addition, we found it difficult to use the standard manual muscle strength testing techniques in brachial plexus patients, especially in the shoulder girdle muscles. We therefore modified the techniques to make it more suitable for use in brachial plexus patients, and to enable a major part of the examination in the sitting position. Although palpation of the muscle being tested is not required for assessment of motor grades 2–5, it is prudent to assess activity in the muscle being tested at all times. Narakas describes five levels: the roots; the anterior branches of the spinal nerves, the primary trunks, the secondary cords and the peripheral nerves.20 More practically, there are two important levels: avulsions and ruptures. Avulsions can only be treated with nerve transfers, whereas with ruptures, the option of nerve repair with grafting exists. There are many muscles to test and all muscles have more than one root origin.21 A consistent sequence of examination is thus necessary. Intuitively, it makes sense to ‘walk’ the nerves (Figure 14.5). This is only possible if there is a clear picture of the anatomy in one’s head. In the beginning, it is always helpful to have a diagram at hand and record the findings in a chart (Figure 14.2B).

It is logical to begin by ‘walking’ the C5 root, the most cranial and proximal part of the plexus. The first branch is the phrenic nerve. The clinical test for a raised hemidiaphragm is percussion of the chest wall in inspiration and expiration. There should be an additional two intercostal spaces of resonance with inspiration. This test is hard to administer accurately, and a quick glance at the chest X-ray will usually give the required information accurately and more efficiently (Figure 14.6).

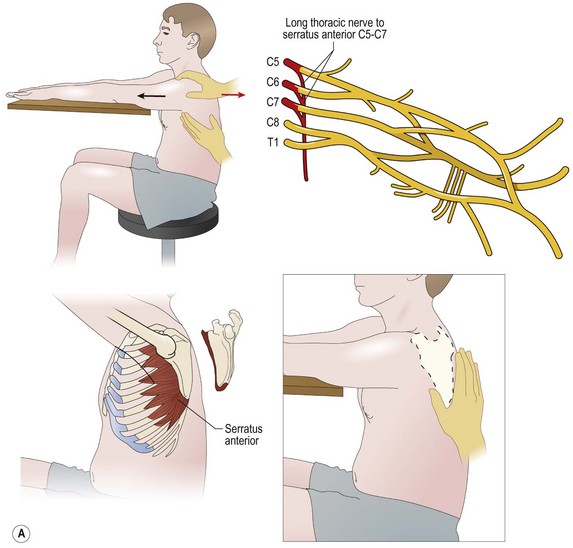

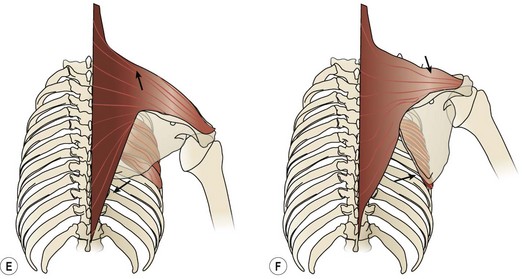

The next branch of C5 is the long thoracic nerve, which also receives contributions from C6, C7, and occasionally C8. These branches arise very proximal, near the foramina. Paralysis or weakness of the serratus anterior, supplied by this nerve is strongly indicative of an avulsion of one or all of the roots of supply. It is impossible to test the serratus anterior in brachial plexus patients in the conventional manner by asking them to push against a wall. To overcome this, one has to use a modified test. The test is performed in a sitting position with both arms outstretched on a table in front (Figure 14.7A). The examiner uses his thumb and fingers to track the movement of the scapula and feel the serratus (Figure 14.7A). The patient is asked to project his entire extremity forward and the examiner feels for the movement of the scapula away from the midline (protraction)(Figure 14.7B). If the patient is able to move, it indicates M2 grade (movement with gravity eliminated). If he is unable to move, the examiner feels for a palpable contraction under his fingers (M1), and no contraction would indicate M0. If the patient has M2 power, the examiner offers resistance with his free arm over the anterior aspect of the shoulder to determine M4 (some movement with resistance) or M5 (normal)(Figure 14.7C). If the patient is unable to move against resistance, he needs to be examined in the supine position. The examiner supports his upper limb with one hand and feels the scapula with his other hand. The patient is again asked to move his limb forward, and if he is able to do, it indicates M3 (movement against gravity)(Figure 14.7D). There are many subtleties to winging, and paralysis of the trapezius and/or the rhomboids can also cause winging. In a serratus anterior palsy, the inferior angle of the scapula is separated from the thorax and pulled backwards to the spine (Figure 14.7E). On the other hand, in trapezius palsy, the scapula moves outwards and forwards (Figure 14.7F). When both muscles are paralysed, the entire medial border is lifted up.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree