Physical Examination

The data provided by the history and observations made during the history taking process will provide focus for the physical examination. Before and during the history, the clinician may have the opportunity to observe posture, stance, gait, and sitting behavior. For example, a person with levator spasm will often sit forward on the chair and rest more of her weight on one buttock or the other. Sitting perfectly straight often aggravates the pain from this disorder.

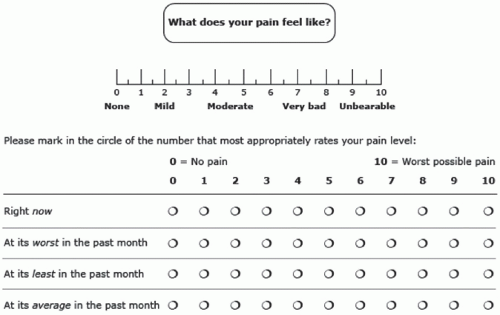

The abdominal examination in a woman with CPP may be more informative if done in the following manner. Ask the patient to point to the area of pain with one finger and outline and circle the area involved. Ask her then to press as hard as she feels it is necessary in order to elicit the pain she experiences. Done in this manner, the impact of her anxiety about being examined may be diminished and a more accurate assessment of tissue sensitivity obtained. The patient is then asked to flex the abdominal muscles by raising only her head off the table and then asked to repeat the same palpation. If the pain elicited by palpation with the abdomen flexed is either the same or greater than the pain of the first palpation, then the abdominal wall itself is likely to be a source of the pain or a “pain generator.” This is a positive Carnett sign. If pain from palpation of the tensed abdominal wall is less, then an internal visceral source(s) is more likely.

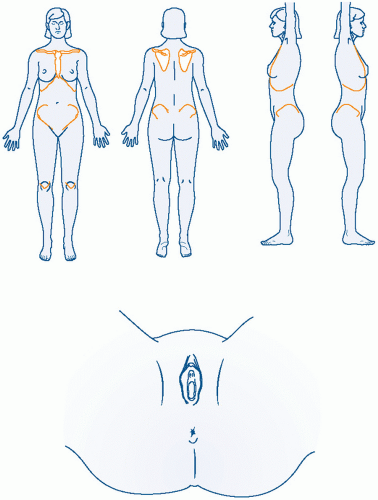

The abdominal wall should then be systematically palpated by the examiner’s index finger in an effort to identify local spots of tenderness or “trigger points.” A trigger point is a hyperirritable spot within a taut band of skeletal muscle fibers that is painful on compression and may give rise to referred pain, tenderness, tightness, and sometimes, local twitch response and autonomic phenomena.

26,27 A diagrammatic record of the examination findings is valuable.

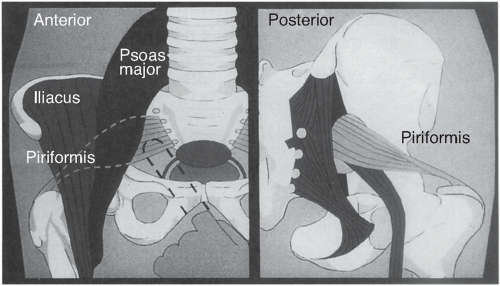

Specific elements of the musculoskeletal examination should be performed to look for piriformis spasm and/or psoas muscle pain. The piriformis originates at the lateral margin of the sacrum, traverses the greater sciatic

notch, and inserts on the greater trochanter of the femur. Its function is to externally rotate the thigh. It also forms a muscular bed for the sacral plexus of nerves in the pelvis, and some or all of the sciatic nerve goes through the belly of the piriformis in 25% of women. With her hip and her knee partially flexed (i.e., in the stirrups), ask the patient to externally rotate each thigh in turn against resistance. Pain in the posterior hip area with this maneuver suggests piriformis spasm. Irritation of the sciatic nerve by this spasm can cause hyperreflexia and “pseudosciatica” or pain that mimics sciatic nerve compression seen in lumbosacral disc disease.

In the lateral decubitus position, the hip is actively and passively extended and flexed. Pain with these maneuvers suggests a psoas muscle origin. Further elements of the musculoskeletal screening examination are discussed elsewhere (

Table 7.2).

23The pelvic examination in the patient with CPP is more informative when performed in a careful stepwise fashion. Meticulous attention is paid to each potential contributing organ system. While collecting this information, the examiner should be thinking of making a list of contributing factors, not examining until “the cause” of the pain is found. First, place one index finger in the vaginal introitus and ask for voluntary contraction and relaxation. Inability to exert conscious control of the bulbocavernosus muscles suggests vaginismus. This diagnosis should, of course, be corroborated by additional history. The presence of good voluntary control during pelvic examination does not exclude the diagnosis of vaginismus that may occur during sexual situations.

28Extending the index finger beyond the bulbocavernosus muscle, one can usually palpate the levator muscles on the right and left sides at approximately the 4:30 and 7:30 positions. In the asymptomatic person, a sense of pressure is experienced. When levator spasm is present, gentle palpation on these muscles may reproduce the patient’s sense of pelvic pressure (a “falling out” sensation) and/or the pain of dyspareunia. Further verification is obtained when the symptom is exacerbated by voluntary contraction of the levators.

The next step is to press directly on the coccyx, reaching it with the vaginal finger by going around the rectum on either side. External palpation of the coccyx combined with this maneuver will normally allow it to flex and extend through an approximately 30-degree angle. This is normally not a painful maneuver. If pain is present, it may be related to coccydynia or adjacent levator spasm.

The piriformis muscle can be tested by the maneuvers described earlier. When these maneuvers suggest piriformis spasm, this can be further confirmed on pelvic examination. The belly of the piriformis can be easily felt transvaginally when the thigh is externally rotated against resistance. When palpation of the piriformis muscle belly reproduces pain, then spasm is likely to be present. A false-positive interpretation of this maneuver can occur if intrinsic cul de sac disease is present because the vaginal examination finger must traverse this area to reach the piriformis muscle (

Fig. 7.3).

The anterior vaginal wall, urethra, and bladder trigone should be examined either before or after the muscular examinations just described, depending on the clinical situation. In general, it is best to examine the (likely) nontender areas first. This technique helps minimize the tendency to experience pressure as pain (“wind-up”) once pain has been elicited. In many cases, the clinician can make the presumptive diagnosis of chronic urethritis, trigonitis, or interstitial cystitis on the basis of careful history combined with focused digital examination. If complex therapeutic interventions are being contemplated, then cystoscopic confirmation (i.e., cystoscopy with hydrodistention) should first be obtained. In the asymptomatic patient, pressure on the bladder base creates only urinary urgency without replicating the clinical pain.

Unimanual, single-digit transvaginal examination should continue by testing the intrinsic sensitivity of the cervix to palpation and traction. The adnexal areas are then examined in a similar manner, first unimanually and then adding the abdominal hand. Separating the pelvic exam into three discrete steps (unimanual vaginal exam alone, unimanual external exam of lower abdomen alone, and then examining the pelvis bimanually) helps distinguish internal visceral pain from pain originating from the abdominal wall.

Rather than following a rigid sequence, speculum examination should be done at a time when it makes the most sense, depending on the type of pain under consideration. For example, in the patient with a history suggesting posthysterectomy vaginal apex pain, it is probably wisest to complete the muscular examination as well as the adnexal palpation

prior to insertion of the speculum. In this manner, the areas more likely to be

nontender are examined prior to the speculum directly touching the potentially sensitive vaginal apex.

In contrast, if the history suggests an adnexal source of pain, then the pelvic examination should begin with the speculum examination (as is traditionally done). The speculum examination is then followed by a pelvic musculoskeletal exam, leaving the adnexal examination for last. To determine if adnexal pathology exists to a sufficient degree to contribute to the pain, the examiner need only palpate with a single vaginal finger. This avoids confusing the diagnostic picture by using the traditional bimanual exam, which may mingle pain signals from the abdominal wall with those from the adnexa. The gynecologist, focusing on the reproductive organs, may interpret all pain as coming from this system, sometimes leading to overtreatment of the adnexa. Having examined the adnexa for pain with the single-digit exam, the traditional bimanual adnexal exam can then evaluate size, shape, and mobility. Throughout each portion of the examination, the clinician should ask whether any tenderness elicited reproduces the pain of her chief complaint.

Rectovaginal examination remains an essential component of the complete pelvic exam, especially in the case of pain noted with defecation (dyschezia). Insertion of the rectal finger causes the least discomfort if the middle finger is placed gently at the anus and exerts slow, gentle pressure in a dorsal direction. Some clinicians are taught that having the woman bear down will facilitate insertion of the finger. When most patients “bear down,” however, they do a Valsalva maneuver and simultaneously contract the voluntary portion of the anal sphincter. This causes an increase in discomfort and makes digital insertion more difficult. The rectal finger should advance as far as possible, ideally reaching the hollow of the sacrum. In this manner, the entire floor of the posterior cul de sac can be thoroughly evaluated for the presence of irregularities or nodularity that might imply the presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). To fully evaluate the uterosacral ligaments, a rectovaginal examination is done. The uterosacral ligaments can be more accurately assessed by putting the cervix on traction in an anterior direction with the tip of the vaginal finger while palpating the stretched uterosacral ligaments with the rectal finger.

After palpation of the uterosacral ligaments, the bimanual portion of the examination is repeated with sequential palpation with the rectovaginal hand, the abdominal hand, and both hands together. When examining areas that are tender, it is useful to pause and inform the patient that examination of the tender area will only last for a count of “one, two, three …” and will only begin when she feels ready. By time limiting this portion of the exam and allowing the woman to determine when it will commence, the examination is made more tolerable for the patient. When tenderness is elicited,

the clinician should ask whether this reproduces the clinical pain the patient is experiencing.

Office Diagnostic Procedures

Trigger point injections have been well established as a diagnostic and therapeutic technique.

29,30 The trigger point is identified first through palpation and then with the needle before injection. Eliciting the local twitch response, a brisk contraction of the taut band (but not the surrounding normal muscle fibers), is essential for success.

31,

32,

33 Multiple types of local anesthetics (e.g., 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine) have been used with none demonstrably superior to any other. The pain of injection can be substantially reduced by adding sodium bicarbonate (1 mL per 10 mL of 1% lidocaine; 0.2 mL per 30 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine). A 27-gauge tuberculin needle or a 25-gauge, 1.5-in. needle is preferable for injection. The use of botulinum toxin A is appealing for chronic myofascial pain for its local, temporary muscle paralysis and its reduction of neurogenic inflammatory mediators. The effects from botulinum toxin injections may last between 3 and 6 months, although it is costly therapy. If the abdominal wall trigger points can be blocked successfully, then the pelvic examination might then be repeated in order to better understand the contributions of intrapelvic pathology to the patient’s pain.

Similarly, local injection can be used to anesthetize the vaginal apex tissue in an effort to determine whether this tissue is intrinsically sensitive, or whether pain elicited from vaginal cuff palpation on bimanual examination emanates from intrapelvic pathology.

Transvaginal ultrasound examination provides very useful information in evaluating acute pelvic pain. Unfortunately, it is less contributory for the evaluation of CPP complaints. The occasional exceptions to this generalization will be noted as individual pelvic pain syndromes are discussed in the following section.