20.3 Chronic diarrhoea and malabsorption

Diagnostic approach

Clinical assessment

Malabsorption does not present as malabsorption per se. Rather, individuals with malabsorption can present with a wide array of symptoms and physical signs (Table 20.3.1). Diarrhoea is the most common presentation and may be accompanied by loss of appetite, decreased physical activity, lethargy and growth failure. Children with coeliac disease may have decreased appetite, and are often cranky and irritable. In contrast, children with pancreatic insufficiency often develop a voracious appetite. In children with failure to thrive, a detailed dietary history is required. Occasionally, parents manipulate the child’s diet in an attempt to control the diarrhoea, which can lead to significant dietary insufficiency with attendant weight loss. Assessment of the age of introduction of various foods into the diet may give insight to the underlying diagnosis. Onset of symptoms 3–6 months after the introduction of wheat products suggests the possibility of coeliac disease. Onset shortly after the introduction of cow’s milk suggests cow’s milk protein intolerance. History of overseas travel is important, as some unusual infections, such as amoebic dysentery, can cause chronic bloody diarrhoea.

Table 20.3.1 Some symptoms and signs of nutrient deficiencies

| Nutrient | Symptom or sign of deficiency |

|---|---|

| Protein | Growth failure |

| Muscle wasting | |

| Hypoproteinaemic oedema | |

| Fat | Weight loss |

| Muscle wasting | |

| Manifestation of deficiency of vitamins A, D, E, K | |

| Carbohydrate | Weight loss |

| Salt/water | Electrolyte disturbances |

| Growth failure (chronic salt deficiency) | |

| Dehydration (acute loss) | |

| Vitamins | |

| A | Night blindness |

| Skin rash | |

| Dry eyes (xerophthalmia) | |

| D | Rickets |

| Hypocalcaemia | |

| K | Bruising (coagulation defects) |

| E | Anaemia |

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

| B12 | Megaloblastic anaemia |

| Irritability | |

| Hypotonia | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

| Folate | Megaloblastic anaemia |

| Irritability | |

| Minerals | |

| Iron | Microcytic anaemia |

| Delayed development | |

| Calcium | Rickets |

| Irritability | |

| Seizures | |

| Zinc | Diarrhoea |

| Skin rash (mouth, perineum, fingers and toes) | |

| Poor growth |

The nature of the loose stool is important to ascertain, as it provides important clues to the pathophysiology and thus aetiology. Diarrhoea can be thought of in terms of fatty stools (steatorrhoea), watery diarrhoea (osmotic because of carbohydrate malabsorption or secretory disorders) and bloody diarrhoea. Box 20.3.1 provides a differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhoea and malabsorption categorized by the nature of the stool.

Box 20.3.1 Differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhoea and malabsorption categorized according to type of stool

Steatorrhoea

Assessment of general health is important, as many gastrointestinal disorders exhibit extraintestinal manifestations. Cystic fibrosis (see Chapter 14.6), Shwachman syndrome and immunodeficiency disorders (see Chapter 13.2) are associated with infections, particularly sinopulmonary infections. Delayed pubertal development can accompany many chronic disorders but is particularly prevalent in Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 20.2).

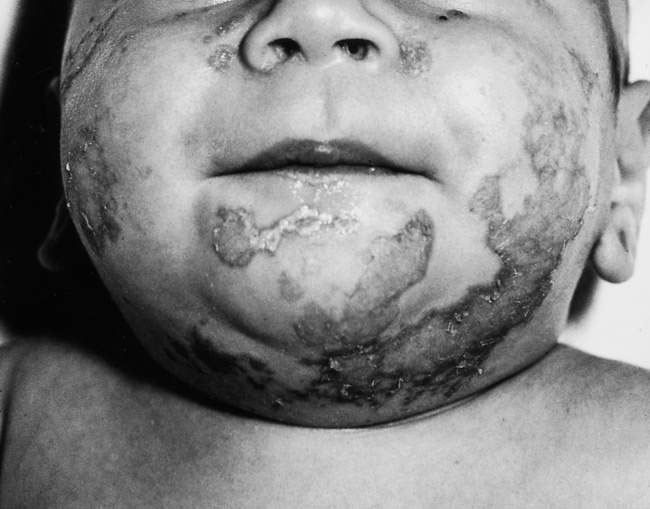

Physical examination includes assessment of growth, nutritional status and pubertal development. Plotting percentile charts is mandatory. A child who is growing normally is unlikely to be suffering from serious gastrointestinal disease. Plotting longitudinal measurements, if available, is very important as it may give clues to the onset of disease and could indicate the diagnosis. Other physical signs of malabsorption and specific nutritional deficiencies include: loss of muscle bulk and subcutaneous fat; peripheral oedema (hypoproteinaemia); bruising (vitamin K deficiency); glossitis and angular stomatitis (iron deficiency); finger clubbing (cystic fibrosis, Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease); skin rashes in coeliac disease (dermatitis herpetiformis) and inflammatory bowel disease (erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum); and specific skin disorders associated with zinc, vitamin A and essential fatty acid deficiencies (Fig. 20.3.1). Rickets is uncommon in our community, although biochemical vitamin D deficiency is quite common and is prevalent in patients with malabsorption, such as in cholestatic liver disease, and coeliac disease. It is important to examine carefully as there are many extraintestinal manifestations of gastrointestinal disease and malnutrition.

Malabsorption with chronic diarrhoea

Some illustrative cases will be provided and a summary of this approach can be seen in Figure 20.3.2.

Fatty diarrhoea (steatorrhoea)

The differential diagnosis of fat malabsorption is quite wide ranging (see Box 20.3.1); however, if one understands the normal physiology of fat digestion and absorption, the differential diagnosis is much less daunting. Conditions that cause steatorrhoea can also be associated with protein maldigestion and/or malabsorption, although symptoms most commonly relate to the malabsorption of fat. The presence of fat in the stool is also more readily observed than protein.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree