6 Child Abuse and Neglect

Epidemiology

Parental Risk Factors for Child Abuse and Neglect

1 Past history of being abused or neglected as a child. Although this is a significant risk factor, it is important to note that not all abused children grow up to become abusive adults. Those who do not have been found to have had a strong, long-standing, and supportive relationship, from early childhood, with a nurturing and nonabusive adult who loved them unconditionally, helped them recognize their own worth, and taught them how to make good choices. This enables them to develop trusting relationships and, hence, better social support systems.

2 Poor socialization and emotional and social isolation. Inadequately nurtured themselves as children, these parents are poorly equipped to adequately nurture their offspring. Their own mothers may not have bonded well with them, and/or their trust may have been betrayed repeatedly by those they loved unconditionally and should have been able to count on most. They may have been shuttled back and forth between the parental home and relatives’ or foster homes or placed in a series of foster homes over the course of years. As a result, they have trouble with trust and forming close attachments, and hence, are poorly equipped to develop and use support systems. They tend to have little understanding of child development and of children’s emotional and other needs and, therefore, of good child-rearing practices and reasonable expectations of child behavior. E-Tables 6-1 and 6-2 present common features of many of the families of origin of abusive parents/caretakers, as well as their child-rearing practices, which then tend to be repeated by these younger parents and by ensuing generations. E-Table 6-3 presents common character traits and historical revelations of many poorly socialized parents/caretakers and of those with character disorders.

3 Limited ability to deal adaptively with stress and negative emotions such as fear, anger, and frustration, compounded by a tendency to lash out violently, verbally and/or physically, in response to negative feelings. This behavior is often learned by example in their families of origin.

4 Alcoholism/substance abuse. When intoxicated or high, such parents may be “out of it” or may be disinhibited in approaching or dealing with their children. They also may be away for extended periods, seeking their substance of choice or the wherewithal to obtain it.

5 Mental illness (e-Table 6-4).

6 Domestic violence in the parental relationship.

7 Being subjected to a sudden spate of major life stresses/crises such as loss of job and financial security; loss of home; loss of parent, spouse, or sibling.

e-Table 6-1 Common Characteristics of the Family of Origin of Poorly Socialized Adults Given in Psychosocial History*

| History | Potential Effect on Children |

|---|---|

| Evidence suggestive of impaired bonding | Failure of bonding in first 6 months results in the following: |

| Maternal depression postpartum | Inability/impaired ability to truly attach, trust, and, ultimately, to nurture |

| Mother chose to go right back to work | Inability to feel empathy or remorse |

| “We were never close” | |

| Separation/divorce/abandonment | Fracture of parent–child bond, especially in early childhood, can result in long-term anger, distrust, emotional distance, self-doubt, and antisocial behavior |

| Discord/domestic violence CPS involvement Alcohol/substance abuse | These situations all may cause the following: Anxiety, fears for self and siblings, for victimized parent Chronic sense of uncertainty Difficulty concentrating |

CPS, Child Protective Services.

* These characteristics are often repeated in subsequent generations.

e-Table 6-2 Common Characteristics of Child-rearing Practices of Family of Origin of Poorly Socialized Adults*

* These characteristics are often passed on to ensuing generations.

e-Table 6-3 Character Traits and Historical Revelations of Parents/Caretakers Who Are Poorly Socialized or Have Character Disorders

| Traits | Revelations in History |

|---|---|

| Self-focused | Unable to truly love/care for another and put the other’s needs first |

| Everything they recount in the history is in relation to themselves | |

| Talk more about themselves than their child | |

| Jealous of spouse’s/significant other’s attention to the child | “She spends too much time with him/her” “She babies him” “She loves that kid more than me” |

| Jealous of child’s preference for spouse/significant other | “He’s a momma’s boy, always wants to be with/run to his mother” “He’ll come to me but then runs right back to his mother” |

| Psychopathic/sociopathic tendencies | Little or no conscience/capacity for empathy/remorse |

| No compunction about lying and lie quite convincingly | |

| Poor impulse control, short fuse, bad temper | History of behavior problems—fights, school suspensions |

| Take little or no responsibility for their own failures; instead blame others | Did not finish school “because the principal had it in for me” Cannot hold a job for more than a few months “because the managers are all nuts” |

e-Table 6-4 Mental Illness Seen in Some Abusive Adults

| Mental Illness | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Severe depression | No energy, often cannot even get out of bed |

| Inability to nurture or relate | |

| Bipolar disease | Cycling of emotional highs and lows |

| Inconsistency (children never know what is going to happen next) | |

| Explosive behavior | |

| Schizophrenia | Hallucinations/delusions/psychosis: including voices postpartum saying the infant/child is “evil,” “must be punished,” “must die” |

Note: Often parents with mental illness are resistant to seeking and participating in therapy and to consistently taking their medications.

Child Risk Factors

2 Being separated at birth from a mother at high risk for problems with attachment because of illness or prematurity, resulting in impaired bonding.

3 Being the product of an unplanned/unwanted pregnancy, with a mother who sought little or no prenatal care.

4 Being small for gestational age, born with congenital anomalies, and/or having a chronic illness (possibly due to parental grieving and guilt, compounded by the chronic stress of caring for a handicapped child).

5 Being perceived as difficult or different.

6 Having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or being oppositional or defiant.

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse is defined as the infliction of bodily injury that causes significant or severe pain, leaves physical evidence, impairs physical functioning, or significantly jeopardizes the child’s safety. Individual states have varying definitions of what constitutes abuse reportable to Child Protective Services (CPS) and law enforcement agencies, and practitioners should become familiar with the guidelines in their own states. Many of the methods used by perpetrators are listed in Table 6-1, and weapons commonly employed are detailed in Table 6-2.

Table 6-1 Methods Used in Physical Abuse

Table 6-2 Weapons Commonly Used in Physical Abuse

The spectrum of severity of injuries caused by physical abuse ranges from isolated surface bruising that may be a product of overzealous discipline to fatal head and abdominal trauma that is the result of extremely violent rage reactions. Important to remember is that relatively unimpressive surface marks or injuries may be associated with far more significant underlying skeletal, abdominal, and CNS trauma (see Fig. 6-13). In addition, it is well known that physical abuse tends to be repetitive and that the severity of attacks tends to escalate over time; so does, correspondingly, the severity of injuries. Given this, early recognition, reporting, and intervention are essential in prevention of increased morbidity and mortality. Early recognition can be difficult for a number of reasons. Children with milder injuries generally are not brought to medical attention and may even be kept from those outside the immediate family until visible bruises or other surface injuries fade. Further, when care is sought, a misleading or deceptive history is almost always given. If a plausible history of accidental injury is provided (as can be the case with more sophisticated abusive parents), abuse may go unsuspected. However, when emergency department physicians make it a general practice to disrobe children and perform a complete surface examination on all those who present with mild or minor trauma, the diagnosis of otherwise unsuspected abuse rises dramatically because of identification of suspicious physical findings on other areas of the body, especially those ordinarily covered by clothing. Because presenting signs and symptoms are often nonspecific, recognition can be particularly challenging when the victim of mild to moderate inflicted trauma is a young infant and has no surface injuries or ones that are subtle and easily overlooked. Listlessness or lethargy, irritability or fussiness, vomiting (usually without diarrhea), low-grade fever, and vague complaints of trouble with breathing in infants with milder degrees of inflicted head injury can easily be interpreted as being due to early viral infection. Irritability due to pain from rib and metaphyseal fractures may be mistakenly diagnosed as due to colic or constipation (which may coexist due to stool withholding secondary to pain). Grunting respirations due to rib pain are likely to be attributed to early pulmonary disease such as bronchiolitis or pneumonitis. Relatively rapid dissipation of pain and tenderness (often within 2 to 5 days) in infants with nondisplaced fractures (due to their thick periosteal covering, which resists tearing and promotes prompt healing) can add to the diagnostic difficulty, particularly when presentation is delayed.

Hence diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion when infants, especially young infants, present with uneplained irritability and/or lethargy, with or without grunting respirations, and with vomiting without diarrhea. Unusual thoroughness in history taking and physical examination is a must. This includes asking if fussiness or irritability is or was worse with movement, on being picked up, or when held by the chest. The physical examination should include a meticulous surface assessment searching for faint bruises or petechiae including a Wood’s lamp examination (see the section Bruises, Welts, and Scars); careful palpation of ribs and extremities for tenderness (with particular attention to posterior ribs and long bone metaphyses); and dilated retinoscopy, all of which can be revealing. When a history of pain on motion or bony tenderness is found or when subtle surface injuries are noted, a skeletal survey is indicated, perhaps followed by a bone scan (see the sections on fractures, under Skeletal Injuries). The presence of metaphyseal and rib fractures and/or retinal hemorrhages mandates a head computed tomography (CT) scan (because of their association with subdural hematomas).

The diagnosis of inflicted injury is established on the basis of a constellation of factors including historical, physical, and behavioral observations. Approaching the case with an open mind, obtaining a thorough present and past medical and psychosocial history, and meticulous physical examination are crucial to ensuring accurate diagnosis of inflicted trauma as well as in preventing overdiagnosis of abuse. Important elements are detailed in Tables 6-3 and 6-4. Radiographs and laboratory studies (complete blood count [CBC] and differential, liver function tests [LFTs], amylase, lipase, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time [PT/PTT], coagulation profile) are useful, not only in identifying and confirming injuries, but also in detecting evidence of occult trauma and ruling out other differential diagnostic possibilities.

Table 6-4 Physical Examination for Suspected Physical Abuse

Common Historical Red Flags

1 Despite no history of injury, injury is found.

2 The history is incompatible with the type or degree of injury. For example, the distribution of lesions or type of injury does not fit the mechanism reported; the history is consistent with a minor injury (shortfall, rolled off couch), but evidence of major trauma is found; or multiple injuries of differing ages are found for which no prior care has been sought or adequate explanation provided.

3 The history of the way in which the injury occurred is vague, or incomplete.

4 The history changes each time it is told to a different health care worker, or even to the same worker who comes back with clarifying questions.

5 The parents, when interviewed separately, give contradictory histories.

6 The history is not credible. The child may be said to have done something developmentally impossible (e.g., having climbed and fallen when he or she cannot even sit, or a younger sibling caused it).

7 No history is reported of changes in behavior in an infant or child who has older injuries of differing ages that would have caused significant pain.

Miscellaneous Historical Red Flags

1 A history or evidence of repeated visits necessitated by “accidents” or injuries (often to a number of different facilities).

2 A history or evidence of repeated fractures or old scars suggestive of prior inflicted injury.

3 A history of repeated ingestions.

4 Poor compliance with well-child care: missed visits, immunization delay.

Behavioral/Interactional Red Flags

1 A significant delay between the time of injury and the time of presentation often exists.

2 The parent may not show the degree of concern appropriate to the severity of the child’s injury.

3 A pathologic parent–child interaction may be observed. A parent demonstrates unusually rough/angry/impulsive behavior toward the child (yells, yanks, hits). A parent displays inappropriate expectations of child (“sit still,” i.e., don’t explore; “watch your brother”). A parent is often clearly unaware of the child’s needs and insensitive to behavioral cues (crying with hunger, dirty diaper, wants to be held or comforted).

Few victims of physical abuse are brought in with a chief complaint of abuse. Most present with a chief complaint of an accidental injury or of an unrelated (cold, rash) or somewhat peripheral (lethargy, irritability) chief complaint. Whenever the physician’s suspicion is aroused by historical or observational findings, he or she (or a designated social worker) should obtain a detailed psychosocial history, seeking more information concerning the family’s current living situation, stresses, and emotional support systems. Particular attention should be paid to recent family crises including personal (ill health, job loss, separation) and environmental (pending eviction, heat or utilities discontinued) crises; degree of isolation (no family or social supports, no phone); and prior problems with family violence, mental health, alcohol, or drugs. Answers to questions about methods of discipline and parental reactions to common triggering events such as prolonged crying, toilet training accidents, and stubborn behavior can be most illuminating, as can answers to questions about how they felt when they learned of the baby’s pregnancy, when they first saw the baby, and what the baby is like (see Table 6-3). Although a detailed history takes time, it can be invaluable in facilitating accurate diagnosis, individualizing care, arranging appropriate family supports, and assisting CPS and law enforcement in their investigations. This and the medical history should be obtained in a supportive, nonjudgmental manner because aggressive interrogation will only serve to alienate the parent, limiting the value of the data obtained.

Table 6-5 presents additional historical and behavioral clues that may become apparent in the course of interviewing the parents/caretakers of an abused child.

Table 6-5 Historical and Behavioral Clues from Caretakers’ Demeanor during Interview

Note: Perpetrators often disclose a watered-down version of what they did when abusing the child when asked what they think might have happened to cause the injuries found.

Physical Findings and Patterns of Injury

Surface Marks

Bruises, Welts, and Scars

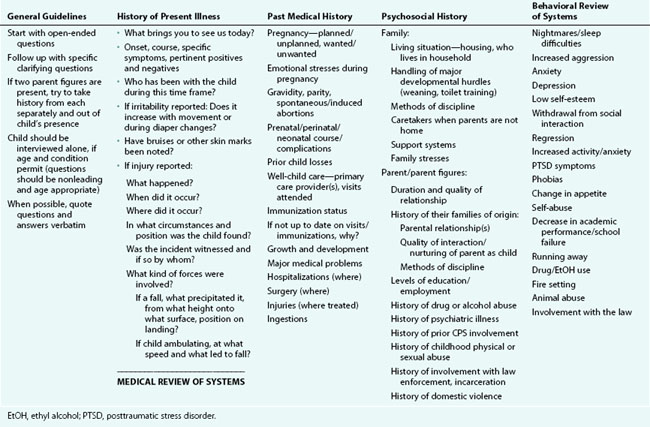

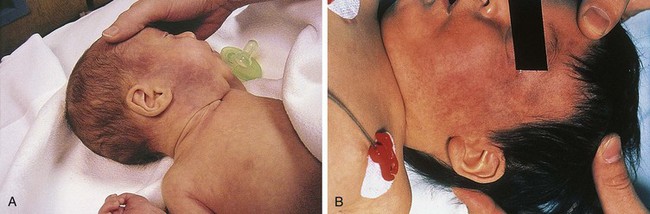

Bruises are the most common clinical finding in cases of physical abuse, seen in up to 75% of victims, and their presence should prompt a search for other, deeper injuries. Inflicted bruises and welts may be the result of direct blows or of impacts with firm objects when pushed, shoved, thrown, or swung into them. They frequently involve more than one plane of an extremity, the torso, and/or head, and are often found in places that are unusual sites for accidental injury (see the section Differential Diagnosis of Inflicted Injuries versus Findings Caused by Accident or Illness, later). These include the back, buttocks, upper arms, thighs, abdomen, perineum, and feet, all of which are typically covered by clothing and, thereby, hidden from public view (Figs. 6-1 and 6-2). When due to slaps or blows, these locations suggest some forethought in site selection. Among other unusual sites are the face (including the periorbital area and eyelids, cheeks, sides of the forehead, lateral aspects of the chin and mouth), ears, neck, hands, calves, and volar or ulnar (defensive posture) aspects of the forearms. Being more exposed, bruises in these areas may reflect greater impulsivity on the part of the perpetrator.

Figure 6-2 This toddler, the victim of repetitive beatings by her mother’s boyfriend while the mother was hospitalized, had A, postauricular bruising, B, a line of fingerprint or knuckle bruises over the posterior left shoulder, and C, extensive bruising over the lower back in a pattern suggestive of knuckle marks, along with a large contusion over the right iliac crest. D, Rounded bruises over the lower abdomen and mons pubis may represent grab or punch marks. Some of her injuries were due to impacts against stairs and furniture when thrown forcefully by the perpetrator. Other injuries included a healing left radius fracture, refracture through a healing distal clavicle fracture, and evidence of old CNS trauma (see Fig. 6-26; Fig. 6-39, B; and Fig. 6-55).

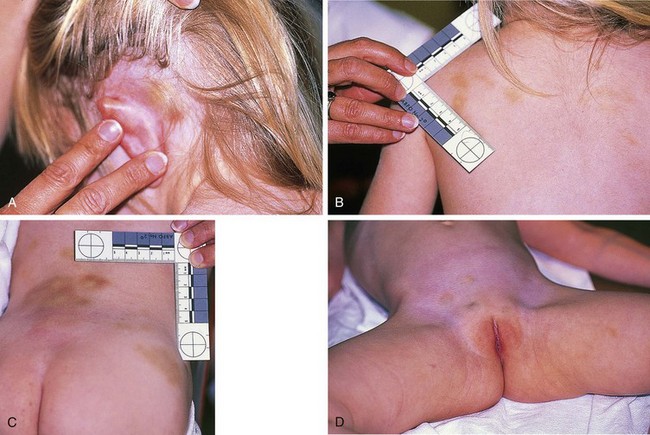

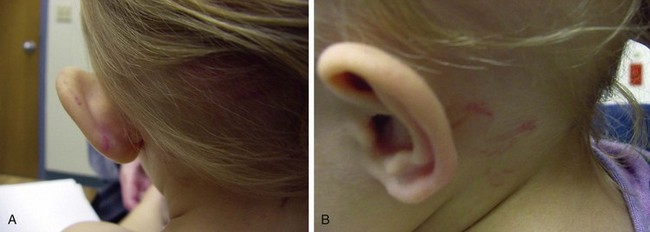

Bruises involving the head, face, mouth, neck, and ears (Fig. 6-3) are seen in a substantial percentage of physical abuse victims: approximately 50% of infants and 38% of toddlers. Subgaleal hematomas and contusions and petechiae involving the scalp may be the result of direct blows or impacts against hard surfaces. On occasion they are caused by forceful hair pulling (Fig. 6-4). Slaps of moderate force may produce diffuse bruising with petechiae (Fig. 6-5). More forceful slaps leave handprint marks, consisting of petechial outlines of the fingers of the perpetrator as maximal capillary distortion occurs at the margins of the fingers on impact (Fig. 6-6). Periorbital and eyelid bruises in the absence of evidence of an overlying forehead hematoma or abrasion, or of an accidentally incurred frontal skull fracture, are likely to be inflicted and caused by direct blows to the face (Fig. 6-7, A and B).

Figure 6-4 Subgaleal hematomas. This toddler, in the care of mother’s paramour, was reportedly well until about 45 minutes after being put to bed, when she “woke up screaming.” On being picked up, she was noted to have a “mushy head.” At the hospital, she was found to have large bilateral subgaleal hematomas, with surface bruising and petechiae over the occipitoparietal scalp. She also had semicircular bruises behind her left ear consistent with fingernail marks. Skull radiographs and a head CT scan showed no evidence of skull fracture or intracranial injury. Further examination revealed extensive bruising and lacerations of the introitus consistent with sexual assault (see Fig. 6-92 B). The perpetrator apparently grabbed her by her hair and by her head, leaving fingernail marks while in the process of assaulting her. Her hair was pulled so forcibly that the scalp was pulled away from the skull, leading to the extensive subgaleal bleeding, which continued to expand over the ensuing 72 hours. A, Thinning of the hair from hair loss and bruising of the scalp are evident, and the subgaleal hematoma over her left temporal area is so large that it is pushing her external ear out laterally. B, Curvilinear marks behind her left ear are fingernail impressions.

Round impressions of the thumb and forefinger may be seen on the cheeks, sides of the forehead, or sides of the chin in infants and young children who have been grasped and forcefully squeezed (see Fig. 6-1, B). Similar fingerprint bruises may be noted on the upper arms, trunk, abdomen, or extremities where the infant has been grasped and held tightly while being shaken or forcibly restrained (see Fig. 6-13). More elongated grab marks may also be found on the extremities (Fig. 6-8). When round bruises similar to fingerprint marks are found in a linear pattern, they may be fingertip impressions or knuckle marks from punching (see Fig. 6-2, B and C). In the latter instance, one may note partial central clearing of the rounded contusions. Fingerprints or grab marks located on the thighs, especially the medial surfaces, should prompt careful examination for signs of concurrent sexual abuse. Pinching produces apposed fingerprint marks with a shape that may be reminiscent of a butterfly or figure-of-eight. These may be seen singly or in rows, usually on clothing-covered areas (Fig. 6-9).

Figure 6-9 Pinch marks. A row of fading bruises secondary to pinching, used as a method of discipline by his mother, is seen on the lateral aspect of the thigh of this preschool-age boy. More than a year later, his sister nearly died of multiple stab wounds also inflicted by their psychotic and delusional mother (see Fig. 6-16).

Attempted smothering, choking, or severe and prolonged thoracic compression may produce showers of petechiae over the shoulders, neck, and face (Fig. 6-10, A–D). The oral and conjunctival mucosa may be involved as well and should be carefully inspected. If a hand or other object is held forcefully over the nose and mouth of a child with erupted teeth, imprint bruises, abrasions, or lacerations left by the teeth on the labial mucosa may be noted in addition to facial petechiae (see Fig. 6-10, E). When strangulation is the mechanism, neck bruises are usually visible (see Fig. 6-10, B). These petechiae may range from florid to faint and may be especially subtle when there has been a delay in seeking care. They can be mistaken for a rash if the examiner fails to check for blanching. Failure to detect such lesions has resulted in a number of subsequent deaths.

Bruises are often seen over the curvature of the buttocks and across the lower back after severe spankings, whether with a hand or an object such as a paddle, belt, or hairbrush (Fig. 6-11). When linear marks from fingers, belt, or brush edges are seen, these tend to be horizontally or diagonally oriented (see Fig. 6-11, B). However, in some cases a linear pattern of petechiae may be noted on either side of the gluteal crease (see Fig. 6-11, C). Despite their vertical orientation, these are also the result of forceful horizontal blows across tightly tensed glutei, as when the blows are delivered, the involved sites are closely apposed along the crease and thus are subject to maximal capillary distortion on impact.

Bruises involving the abdominal wall below the rib cage and above or anterior to the pelvic girdle are rarely seen with accidental injury and are relatively unusual in cases of abuse (see Fig. 6-2, D and Fig. 6-13). This is because of the great flexibility of the abdominal wall and its padding with adipose tissue. In fact, many children with inflicted intraabdominal injuries have little or no cutaneous evidence of trauma over the abdomen, although in some cases their absence may be due to delayed presentation. When abdominal bruises are present, they are indicative of forceful grabbing or pinching or of forceful blunt impact (such as a punch or kick). In these cases, abuse should be strongly suspected and evidence of internal injury should be sought (see the section Abdominal and Intrathoracic Injuries, later; and Fig. 6-57).

In many instances the surface marks are recognizable imprints of the edge of a weapon used to inflict the injury, because the edge causes maximal capillary deformation on impact. Those most commonly seen are looped-cord marks, caused by whipping the child with a looped electrical cord (Fig. 6-12, A and B), belt and belt-buckle marks (see Fig. 6-12, C, D, and F; see also Fig. 6-11, B), and switch marks (see Fig. 6-12, E and F); but almost any implement can be used including hairbrushes (see Fig. 6-11, B), shoes (see Fig. 6-12, G and H), kitchen utensils (see Fig. 6-12, I), and chains (see Fig. 6-12, J).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree