3.9 Child abuse

Development of current concepts

A web link to the various Australian states’ child protection legislation is: http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues22/issues22.html.

• Child abuse is physical or psychological harm from acts of commission by parents or carers.

• Harm from omission occurs when nutrition, hygiene, health and housing needs are neglected.

• Between 50% and 70% of parents who harm their children were harmed when they were children.

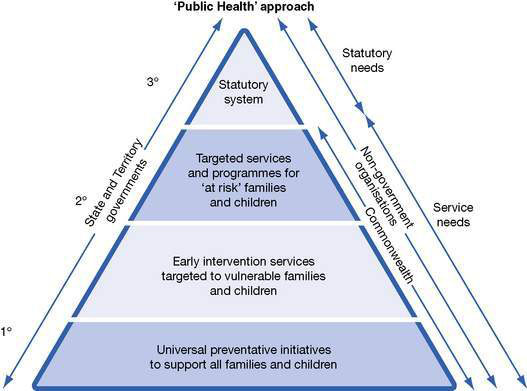

The Australian National Child Protection Framework represents the public health approach as a pyramid (Fig. 3.9.1).

Child protection and the concept of mandatory reporting

A useful summary of the issues related to the mandatory reporting of child abuse was published by the Australian Institute of Family Studies in 2005 (web reference: http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/sheets/rs3/rs3.html).

Prevalence of child abuse in Australia

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (www.aihw.gov.au) is responsible for collecting and collating child protection data from throughout Australia. The total number of notifications made nationally, reflecting the number of children in whom child abuse or neglect is suspected, has increased annually from 107 134 in 1999–2000 to 339 454 in 2008–2009. New South Wales contributed 63% of the total notifications. The increase reflects changes in child protection policies and practices, and an increased public awareness of child abuse. It is not clear whether the increased rate of notification is due to an increase in child abuse. In Australia, estimates of the current incidence of child abuse range between 10 and 20 cases per 1000 live births.

Principles of interagency practice in relation to the management of suspected child abuse or neglect

• the presence of policies, procedures and guidelines to address roles, responsibilities, referral practices, timeframes for assessments

• a process for the exchange of information in relation to children who are suspected of having been abused in the context of what is legally appropriate and professionally ethical

• a joint decision-making process between tertiary agencies specifically related to the outcomes and interpretations of assessments, the types of intervention and the provision of treatment to abused children.

Health

• Recognition of adversity in families and ensuring its active resolution

• Recognition of children in whom abuse/neglect may have occurred

• Ensuring that the child’s situation is properly assessed in relation to health and safety needs

• Complying with local legal notification requirements for suspected abuse/neglect

• Determining the ongoing role of the health agency according to agreed interagency practice

• Working to maintain an ongoing professional relationship with families after abuse has been suspected

• Provision of specialist forensic health services to children suspected of having been abused or neglected, complementing community services and the police. These include forensic medical and psychosocial assessment and therapeutic services.

Community services

• Investigation of notifications/reports of suspected child abuse/neglect

• Coordination with health units and police of each agency’s respective role

• Facilitation of the assessment of children in whom abuse/neglect is suspected

• Establishment of the level of danger/safety of children who have been abused or neglected

• Seeking of court child protection orders, when considered necessary, for abused/neglected children, particularly for those who remain in unsafe circumstances

• Optimal placement of children removed from their families because of abuse/neglect

• Ensuring that adequate therapy is provided to children in whom abuse/neglect has been substantiated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree