Abstract

The Importance of ‘Human Factors’ for Maternity Teams

Key Facts

In obstetric practice, human factors play an important role in adverse events associated with cardiotocograph (CTG) interpretation and management of obstetric emergencies. Therefore, multiprofessional training in maternity care should incorporate human factors as an essential component.

The Importance of ‘Human Factors’ for Maternity Teams

The aviation industry has embraced human factors training for more than four decades and there is a growing interest in applying human factors sciences in healthcare with the same goals of reducing error, promoting efficiency and enhancing patient safety [1]. In 2005, Elaine Bromiley died because of several unintended human factor errors when a general anaesthetic was given for a simple day case operation. This gave impetus to the development and more widespread uptake of human factors in healthcare. Martin Bromiley, Elaine’s husband, is an airline pilot trained in human factors and went on to establish the Clinical Human Factors Group [2]. Although the aviation industry and obstetrics differ in many ways, similarities can be identified and cross-learning applied. Both involve specialised multidisciplinary teams working around the clock, operating in highly technical and complex environments, where outcomes are expected to be good. In both areas, serious accidents are rare, mostly unexpected and are always very tragic events. It seems appropriate that healthcare is also considered to be another ‘safety-critical industry’.

There is good evidence that human factors play an important role in serious incidents in maternity care. The recent MBRRACE-UK report confirmed that human factors remain highly relevant in maternal deaths [3]. Regarding fetal and neonatal deaths, multiple reports over the years have identified human factors as a significant contributory cause of untoward outcomes. The Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy (CESDI) reports found that in 52% of 873 cases of intrapartum fetal deaths the care received was likely to have been suboptimal where different management would likely have affected the outcome [4]. Recurrent themes in the series of CESDI reports were failure to recognise (situation awareness), failure to refer (communication) and inappropriate delegation (leadership/teamwork). The most recent report from the RCOG ‘Each Baby Counts’ initiative in the United Kingdom, looking into the care of babies born in 2016 who subsequently died in the early neonatal period or sustained a severe hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, concluded that human factors were a critical contributory cause identified in 50% of cases where different care might have made a difference to the outcome [5, 6].

If we reflect on our own obstetric practice, most obstetric adverse events relate to non-technical skills (NTS) errors. A critical analysis of obstetric serious untoward incidents (SUIs) in two London hospitals confirmed that 82.6% involved human factor errors (with multiple factors apparent in 78.9%). The ‘Human WORM’ classification (Workmanship, Omissions, Relationships and Mentorships) was used to analyse cases and NTS errors were the most common underlying cause: ‘Omissions’ in 61.6% of cases (situational awareness, decision-making errors), ‘Relationship’ issues in 47.7% (communication, team working errors) and Mentorship’ in 31.2% (lack of senior presence, etc.). ‘Workmanship’ errors were involved in only 44.2% of SUIs (i.e. knowledge or technical skills issues). There were no differences in the contribution of the various elements in two neighbouring units (one a general hospital and the other a tertiary referral centre) [7]. It is useful to have tools available which encourage a comprehensive initial assessment but also encourage further review as the situation develops. (Vignette 1: SHEEP model). Human factors sciences work at a system level to ensure that the organisation design supports safety [8]. On an individual/team level there is also room to promote awareness of human characteristics, developing strategies to reduce the impact of these factors on performance and ultimately enhancing patient safety and outcome.

While it is critical that all healthcare staff (professionals and ancillary) have the education and training necessary to perform their roles, training itself is generally a weak safety intervention. Human factors sciences must also assess whether training is likely to be effective or ineffective for improving patient safety. Effective training must be complemented by robust system design [9].

Both on individual and team levels, human factors awareness can be incorporated with technical skills training. Elements including team communication, leadership, followership, decision-making and situational awareness should be integrated within emergency skills drills training programmes.

Historically, the ‘person approach’ process has been used to manage error in medicine. This often led to blame levelled against one or more individuals – usually the healthcare worker(s) at the ‘sharp end’ of patient interaction. The ‘system approach’ accepts that error is an inevitable consequence of the human state, even in the most expert and aware organisations. ‘High Reliability Organisations’ (HROs) aim to minimise risk and use a system approach for handling error. They acknowledge that ‘To err is human’ and accept that while ‘error is inevitable; harm is not’ [10]. HROs ensure that ‘health, safety and environment’ (HSE) are an integral and expected part of their structure. The wellbeing and training of staff take equal priority with a philosophy that ensures that robust systems are in place to reduce the likelihood of error and consequent harm.

In real-life obstetric emergencies, a team debrief following the event can aid reflection and understanding of the human factors involved. Debrief is not something that must only be associated with an emergency or an event where something has gone wrong. It can be usefully applied after a normal labour ward shift when teams gather for handover. It can be an opportunity to deliver praise, helping to embed continuous improvement in care.

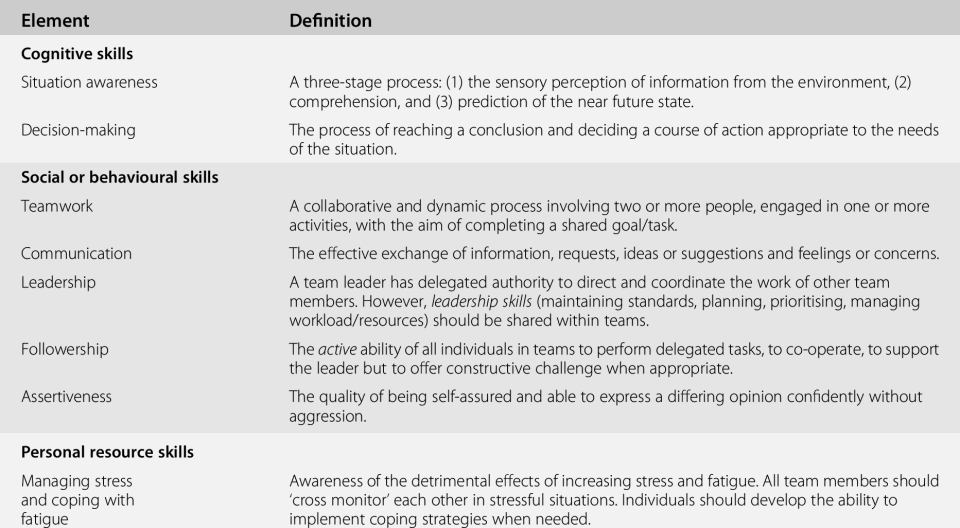

Throughout the chapter, the various elements which make up non-technical skills will be reviewed individually (Table 41.1). The authors’ main aim is to introduce the reader to the concept of human factors and encourage non-technical skills training alongside ‘standard’ skills and drills training in obstetric emergencies. At the end of the chapter you can find additional tools including links to videos and a list of suggested further reading to support human factors training in your own setting.

| Element | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cognitive skills | |

| Situation awareness | A three-stage process: (1) the sensory perception of information from the environment, (2) comprehension, and (3) prediction of the near future state. |

| Decision-making | The process of reaching a conclusion and deciding a course of action appropriate to the needs of the situation. |

| Social or behavioural skills | |

| Teamwork | A collaborative and dynamic process involving two or more people, engaged in one or more activities, with the aim of completing a shared goal/task. |

| Communication | The effective exchange of information, requests, ideas or suggestions and feelings or concerns. |

| Leadership | A team leader has delegated authority to direct and coordinate the work of other team members. However, leadership skills (maintaining standards, planning, prioritising, managing workload/resources) should be shared within teams. |

| Followership | The active ability of all individuals in teams to perform delegated tasks, to co-operate, to support the leader but to offer constructive challenge when appropriate. |

| Assertiveness | The quality of being self-assured and able to express a differing opinion confidently without aggression. |

| Personal resource skills | |

| Managing stress and coping with fatigue | Awareness of the detrimental effects of increasing stress and fatigue. All team members should ‘cross monitor’ each other in stressful situations. Individuals should develop the ability to implement coping strategies when needed. |

Key Issues

Situational Awareness

Mica Endsley defines situational awareness (SA) as ‘the perception of the elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future’ [11]. The simplest way is to consider this at three related levels: perception (what?), comprehension (so what?) and projection (what’s next?) A simple model adapted from Endsley is shown in Figure 41.1.

– What?

PERCEPTION of elements in the environment

– So What?

COMPREHENSION of the current situation

– What next?

PROJECTION of the near-future status

Figure 41.1 Model for situational awareness.

Level 1

is perception of information received from the environment using all of our senses. ‘Sensory storage’ can hold information only very briefly: between 0.5 seconds for visual and 2.0 seconds for auditory memory [12]. If we are concentrating and paying attention to one task, something very obvious can happen right in front of our eyes and we won’t ‘see it’ (i.e. ‘inattentional blindness’; see the text that follows). This was illustrated in Chabris and Simons’ classic psychology experiment: ‘The Invisible Gorilla’. They arranged two teams of students in white or black T-shirts. Each team passes a basketball to each other, while the audience is asked to focus on counting the exact number of times the white team passes the ball, ignoring the black team’s passes. Despite this occurring in an area no larger than a small labour room, half of the observers missed an adult in a full-sized black gorilla suit crossing the room [13]! This error of perception is known as ‘inattentional blindness’ and demonstrates the need to learn how to maintain SA, particularly in the presence of multiple distractions and interruptions. Maintaining SA is difficult when one is ‘task-focused’ (e.g. when asked to count one team’s basketball passes)! Examples from our labour wards include (1) being distracted during epidural placement and becoming ‘blind’ to the pathological CTG and (2) in a twin delivery focusing on the delivery of the second twin and ‘not seeing’ the heavy bleeding continuing from the episiotomy made with delivery of the first twin.

The other key point in perception is that we ‘tend to see what we expect to see’ (known as confirmation bias and expectation bias). A typical example is during a drug cross-check. We should always ask ‘What is this?’ and we should not say ‘Check this magnesium sulphate 10%’. The ampoule in your hand might actually be magnesium sulphate 50%. The unintentional bias caused by the wording used may lead to the wrong dose being administered. Saying what your checking colleague expects to see can introduce confirmation bias. This is influenced by the level of trust between individuals, seniority, time pressure, interruptions, distractions, and so forth. These are two of several ‘cognitive biases’ which may lead to error and harm.

Another risk on the labour ward related to perception is the ‘loss of awareness of the passage of time’. Perceiving the passage of time is influenced by our cognitive workload, levels of stress and focus. It can of course, be vital to focus on a difficult task and shut out everything else around you, for example, trying to locate an epidural space on someone with high body mass index (BMI) or attempting to deliver the posterior arm in a shoulder dystocia. But when we are (over)-focused on a task we can easily lose track of time! That is why in obstetric emergencies it is crucial to allocate a team member to be the timekeeper and for someone who is not ‘task-focused’ to stand back and maintain a situational leadership role. The timekeeper’s role is record and monitor time checks for the whole team. In declared obstetric emergencies, the timekeeper role is usually allocated to a healthcare assistant, but what about the routine case that suddenly becomes complex? You will need to consider when you should ask for someone with more knowledge of the complex manoeuvres to record time spent undertaking each manoeuvre. They can then highlight when it is time to move on to the next manoeuvre (e.g. in a more complex shoulder dystocia).

It’s time now to introduce the important concept of ‘self-awareness’ which is an important part of maintaining situational awareness. This includes asking oneself questions such as: ‘Am I tired?’ ‘Why am I taking so long doing this task?’ ‘Am I out of my depth?’ ‘Do I need help?’

Level 2

is comprehension, the assimilation and interpretation of the information we receive. This occurs in short-term memory, which is where we are ‘consciously aware’. Storage in working memory is limited, holding a maximum of seven ‘bits’ of information only and is therefore easily overloaded. External distractions or interruptions can interrupt cognitive processing and lead to error. Over time, ‘expert tasks’ become automatic and are embedded in long-term memory (e.g. managing a low-cavity operative delivery). This is an advantage for the more experienced accoucheur, as it frees up ‘bits’ within working memory, allowing better SA.

When we make sense of what we have perceived it becomes a working ‘mental model’ (problem definition/diagnosis) stored in long-term memory. Problems can arise when we assume that others know what we are thinking. Expressing our thoughts clearly to the team and constructing a ‘shared mental model’ is a key skill which can help team function and ensure safety in complex or emergency situations. It is also important to acknowledge that in moving from perception to comprehension, clinical situations evolve over time and our comprehension will be limited if we do not update plans in the light of new information. Changing a decision is not ‘indecision’ – a decision may need to be changed if new information is available or when goals are not met and the patient remains unstable.

A good example of poor comprehension despite good perception is when accelerations synchronous with contractions on the heart rate recorded on the cardiotocograph (CTG) are noted during active pushing without realising that in fact it is the maternal iliac pulse rate and not the fetal heart rate that is being recorded. In the active second stage of labour, maternal heart rate is likely to show accelerations during contractions while the fetal heart rate is more likely to show decelerations. To mitigate the risk of wrongly displaying maternal pulse on the CTG leaving the fetus unmonitored, both education and technology can be used. Education in CTG interpretation should highlight that accelerations synchronous with contractions in the active second stage of labour should always prompt the team to exclude maternal pulse being monitored instead of fetal heart. Some CTG machines record and display the fetal and maternal heart rates separately to mitigate against this risk. Use of fetal ultrasound or application of a scalp fetal electrode can also help to differentiate between maternal and fetal heart rates [14].

Level 3

is projection, or the ability to predict the ‘near future state’. This relies on experiential learning which is stored in long-term memory and uses ‘pattern recognition’. This is a primitive but well-developed process in humans which happens automatically, with minimal conscious processing. However, it is prone to error if the pattern is misinterpreted. If no pattern is recognised, then automatic cognition does not function effectively and the process can be distorted by pre-existing biases. More experienced practitioners build up a series of ‘mental models’ or ‘schema’ which are stored in long-term memory and consist of specific patterns or sensory clues which are associated with a particular meaning. This anticipatory function feeds directly into decision-making processes and is prone to error in the presence of distractions or interruptions.

In a situation in which an obstetric team is managing a large atonic postpartum haemorrhage after a forceps delivery, the registrar will be focused on managing the atonic uterus. While applying fundal and possibly bimanual pressure, he or she will also be examining the genital tract to exclude trauma. Their SA can be compromised merely because they are very ‘task-focused’. They may fail to consider impending cardiovascular instability or hypovolaemic shock. If the initial team lead becomes focused on a technical task, someone else must ‘step back’ and maintain a ‘helicopter view’ for the team. They need to confirm they are taking the lead, keeping a careful eye on the patient’s overall condition and watching out for the ‘gorilla in the room’. The situational leader may be a senior midwife, particularly if the anaesthetist is occupied with airway management or securing IV access. Effective teams do not rely on hierarchy but ensure a nominated person is keeping an eye on the bigger picture at all times. In an emergency, all team members will have specific roles and tasks to perform, but the ability to watch for overall deterioration, using any spare cognitive capacity, should be encouraged throughout the team. ‘Cross-checking’ is a tool that can facilitate safety. Each member should feel able to challenge others confidently and constructively, checking that planned interventions are correct. This was one of three non-technical skills (NTS) identified by Bahl et al. which were specific to conducting operative vaginal delivery (the two other procedure-specific skills were maintaining both professional behaviour and a professional relationship with the woman) [15].

The importance of maintaining SA cannot be over-emphasised in safety-critical environments. The most recent RCOG ‘Each Baby Counts’ report [5] brought to special attention the contribution that situational awareness and/or fixation errors play in the care of babies who suffered intrapartum/early neonatal death or severe intrapartum hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE). It is now recommended that all members of the clinical team working on the delivery suite, understand the key principles of maintaining situational awareness and that a senior member of staff must maintain oversight of all activity on the delivery suite, especially when others are engaged in complex technical tasks. This is a good example of a strategy that encompasses the needs of individuals (e.g. providing education and training to understand principles of human factors) while ensuring system needs are also addressed (e.g. by ensuring adequate time for multidisciplinary team training using drills and simulation and by maintaining the coordinator role with a supernumerary midwife not engaged with direct clinical care).

Vignette 1 Sheep Model in Practice

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree