Essentials of Diagnosis

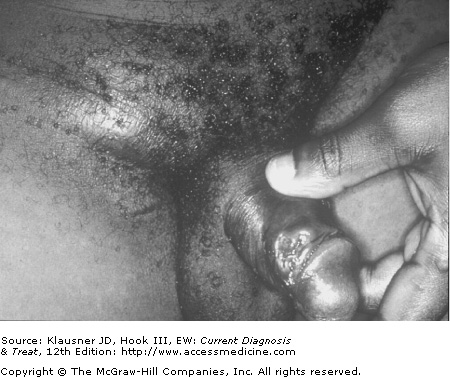

- • Tender papule develops into a pustule after an incubation period of 4–7 days; the pustule ruptures within a few days to produce a nonindurated, painful ulcer with a purulent base and undermined or ragged borders.

- • Unilateral tender inguinal adenopathy may progress to a bubo (fluctuant lymph node mass) that spontaneously ruptures or requires drainage.

- • Isolation of the causative organism, Haemophilus ducreyi, by special culture media.

General Considerations

Chancroid is a sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, a small, fastidious, gram-negative rod. Worldwide, chancroid incidence exceeds that of syphilis in many developing countries. In 1997, the World Health Organization estimated that there were six million new cases of chancroid. Based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, chancroid prevalence has been shown to range from 23% to 56% in endemic areas (Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean). In the United States and western Europe outbreaks are episodic. The infection is also up to 25 times more prevalent in men than in women, a difference recognized in both naturally occurring and experimental disease in humans and macaques. In fact, although controversial, it has been suggested that women may be asymptomatic carriers or reservoirs of the infection.

Although chancroid is uncommon in North America, outbreaks occur in the inner cities of the United States. The most recent of these began in the late 1980s in an outbreak attributed to sexual behavior associated with crack cocaine use and sex in exchange for drugs or money. The number of cases peaked in 1988, when 5001 cases were reported. Since then, the number of cases has sharply declined to an all-time low of 30 cases reported in 2004. Currently chancroid is rare in the United States and Canada.

The reasons for the decline in reported chancroid cases are multifactorial and not completely understood. There did not appear to have been a decline in sexual risk behavior or crack cocaine use in the at-risk populations. Improved provider education and awareness, condom promotion, partner notification and treatment programs, and the addition of chancroid treatment to the syndromic management of genital ulcers all may have played a role. Previous localized chancroid outbreaks appear to have been controlled by identifying and treating reservoir core groups such as commercial sex workers.

A major constraint to understanding chancroid epidemiology has been the lack of sensitive and specific diagnostic tests. The organism is fastidious and difficult to culture. When diagnosis is based on clinical criteria alone, the infection is likely to be grossly over-reported in some circumstances and under-reported in others. The development of sensitive and specific PCR assays for H ducreyi, it is hoped, will correct the problem of misdiagnosis in the future.

Chancroid has been shown to facilitate HIV transmission by providing both a portal of entry and an exit for the virus. In other words, chancroid increases both the transmissibility and the susceptibility of HIV and may do so by two mechanisms. First, increased viral shedding occurs in the ulcer exudates in HIV-infected patients with chancroid, thus making the virus available for transmission during sexual intercourse. Studies have shown that the mere presence of lesions does not always prevent chancroid patients from having sex. Second, recruitment of CD4 cells, the primary targets of the virus, to chancroidal ulcers serves to increase susceptibility of HIV-infected individuals to HIV acquisition. Finally, there are challenges in chancroid treatment among HIV coinfected patients as prolonged duration of ulceration and more frequent treatment failures have been reported.

Pathogenesis

H ducreyi enters the skin through microabrasions that occur during sexual intercourse. A local tissue reaction leads to development of an erythematous papule that progresses to a pustule. The lesion then undergoes central necrosis to ulcerate. Histologic evaluation of these lesions reveals a deep necrotic ulcer surrounded by an infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages, Langerhans cells, and CD4 and CD8 cells. Viable H ducreyi are demonstrable in lesions, but very few organisms have been found within phagocytes. This finding, combined with a lack of interaction noted between the organisms and surrounding cells, suggests that H ducreyi is primarily an extracellular organism with the ability to resist cellular uptake and phagocytosis through mechanisms that have not yet been completely elucidated.

H ducreyi pathogenesis has been studied in tissue culture, animal models, and a human challenge model. Virulence factors identified include the presence of a pilus, lipooligosaccharide, a cytolethal distending toxin, a hemolysin, a hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein, a copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, a zinc-binding periplasmic protein, and a filamentous hemagglutinin-like protein. These potential virulence factors and isogenic mutants of H ducreyi developed to facilitate examination of these factors have been studied extensively in tissue culture, animal models, and human challenge models. H ducreyi virulence is no doubt multifactorial, as is the case for many other organisms.

Prevention

Prevention and control of chancroid is important for several reasons. Foremost among these is the association of chancroid with HIV transmission in parts of the world where both infections are endemic. Because chancroid lesions are often painful, patients often seek and receive treatment early, making it possible for partners to be notified and treated in a timely manner. Chancroid thrives in populations with high sexual activity, especially where many men are having sex with relatively fewer women, usually sex workers. If these factors can be reduced significantly, transmission will slow or even cease and chancroid prevalence will markedly diminish.

Successful chancroid control has been carried out in Thailand and other countries where multifaceted interventions have been implemented. Promotion of condom use, syndromic management of genital ulcers, treatment of patients who have reactive syphilis serology, contact tracing and treatment, education, and monthly presumptive treatment with azithromycin have contributed to reductions in chancroid and genital ulcer disease in Thailand and South Africa. Treatment of core groups in Canadian epidemics also has had a dramatic effect on the number of cases of chancroid.

Additional insights regarding chancroid prevention were provided by an H ducreyi human challenge model in which azithromycin not only successfully treated infection, but also blocked experimental reinfections for up to 2 months. Based on these observations it is now thought that the success of the South African intervention trial may have been due not only to azithromycin treatment efficacy, but also to the drug’s prophylactic effect.

Clinical Findings

Chancroid begins as a papule that evolves into a pustule after an incubation period of 4–7 days. The pustule then erodes into the classic nonindurated, painful ulcer with a purulent base and ragged, undermined borders (see Figure 12–1). The ulcers can be single or multiple and usually remain confined to the genital area (see Figure 12–2). Vesicle formation is not a feature of chancroid. In some cases mild constitutional symptoms have been associated with infection.