17.2 Cerebral palsy and neurodegenerative disorders

Cerebral palsy

Prevalence

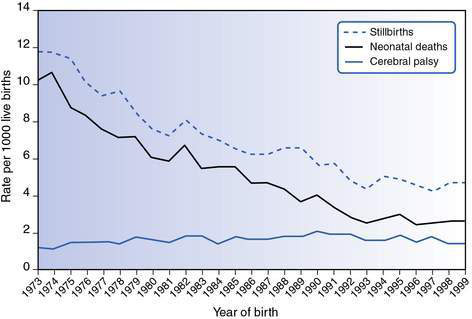

Cerebral palsy is the most common physical disability in childhood. The prevalence of cerebral palsy is between 2.0 and 2.5 per 1000 live births and has remained fairly stable since 1970 (Fig. 17.2.1).

Aetiology

Current knowledge about aetiology

When does the brain insult occur?

• Prenatal events are responsible for approximately 75% of all cases of cerebral palsy.

• Perinatal events contribute 10–15%.

• Postneonatal causes (occurring after 28 days of life) account for about 10% of all cases.

A prenatal cause is assumed in the absence of clear evidence for a perinatal or postnatal cause.

What are the prenatal causes?

What are the postneonatal causes of cerebral palsy?

• Infections, for example, meningitis, encephalitis and septicaemia.

• Injuries may be accidental (such as motor vehicle accidents and near drowning episodes), or non-accidental. Improved road safety and mandatory fencing around home swimming pools are important preventative measures.

• Apparent life-threatening events and cerebrovascular accidents.

• Meningitis, septicaemia and infections such as malaria are important causes of cerebral palsy in developing countries.

• Cerebral palsy is a diverse disorder with multiple risk factors and aetiologies.

• When determining aetiology, distinguish risk factors from causes.

• Most cases of cerebral palsy relate to events long before birth.

• Perinatal asphyxia is responsible for only a small proportion of cases (approximately 8–10%).

• It is important to establish the cause of cerebral palsy if at all possible. It is helpful for families and essential for genetic counselling.

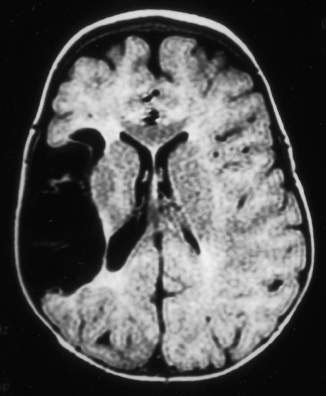

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be undertaken if the cause is not apparent.

Classification

Type of motor disorder

Topographical distribution

• The term diplegia is used where the predominant problem is in the lower limbs but signs are usually also present in the upper limb. Most of these children have normal intelligence. Spastic diplegia is the pattern most commonly seen in premature infants who have the radiological finding of periventricular white matter injury.

• Children with spastic hemiplegia usually have normal intelligence, frequently have epilepsy (50–70%) and visual deficits (homonymous hemianopsia), and may have sensory impairments in the upper limb.

• Children with spastic quadriplegia often have intellectual disability, epilepsy and visual impairment. Poor trunk control and oromotor difficulties may also be present.

Severity of the motor disorder

• Cerebral palsy can be classified according to motor type, distribution and severity.

• GMFCS provides information about severity of gross motor function; MACS provides information about how children use their hands.

• Classifying motor severity using the GMFCS provides information about motor prognosis.

• Co-morbidities such as epilepsy are more common in certain types of cerebral palsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree