Case Management in the Palliative Care and Hospice Settings

Lyla J. Correoso

Linda Santiago

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

Understand the difference between palliative care and hospice care.

Recognize how case management practice applies to palliative and hospice end-of-life care issues.

Describe patient identification and criteria for palliative versus hospice care services.

Explain the main principles and scope of services for palliative and hospice care programs.

Describe the role of the case manager in the palliative and hospice care settings.

IMPORTANT TERMS AND CONCEPTS

Advance Directives

Collaboration

Coordination

End-of-Life Care

Good Death

Health Care Proxy

Hospice Care

Interdisciplinary Team

Palliative Care

Primary Palliative Care Level

Self-Determination

Specialty Palliative Care Level

▪ INTRODUCTION

A. Studies have consistently demonstrated that when patients are asked about their desires for end-of-life care, they indicate that they wish to die free of physical symptoms; they do not want to die alone; and they want to receive care in accordance with personal (especially spiritual) preferences, and in ways that honor the individual’s life and do not present a burden to the family.

B. For more than 30 years, the venue for end-of-life care has been the hospice setting. However, due to multiple barriers, hospice has been underutilized in the United States.

C. Over the past few years, demand for palliative and hospice care has grown tremendously. Palliative and hospice care are provided across a variety of health care settings and professional disciplines. These areas of health care will continue to grow as the American population continues to age and seek desired alternatives to having their health care services met.

D. With the advent of Education on Palliative and End-of-life Care (EPEC) (EPEC, 2006) and End-of-life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) (ELNEC, 2006), there has been a slow but increasing understanding of the importance of symptom control, advanced care planning, hospice care and patient’s preferences, quality of life, and end-of-life care.

E. One long-standing barrier has been the lack of understanding by patients and health care providers, including physicians, about Medicare benefits for hospice.

F. With the explosive growth of palliative care in hospitals and fledgling growth in the community, there has been further confusion with respect to the two levels of care (i.e., primary and specialty care levels).

G. The impact of increased cost to consumers and decreased insurance coverage for service delivery including Medicare capitation for end-stage illness has increased the need for palliative and hospice services in the community.

Capitation has led to the need for utilization of cost-containment strategies to improve the efficiency and quality of services to those clients with end-stage illnesses.

An example of such strategies is the coordination and management of service through palliative care and hospice programs.

H. The number of palliative care and hospice programs have grown in recent years in response to the growth in the population living with chronic, debilitating, and life-threatening illnesses (NHPCO, 2005).

I. Studies suggest that a referral to palliative care programs and hospice results in beneficial effects on patients’ symptoms, reduced hospital costs, a greater likelihood of death at home rather than at an institutionalized facility, and a higher level of patient and family satisfaction than does conventional care (Morrison and Meier, 2004).

▪ KEY DEFINITIONS

A. Advance directive—Legally executed document that explains the patient’s health care-related wishes and decisions. It is drawn up while the patient is still competent and is used if the patient becomes incapacitated or incompetent.

B. End-of-life care—Care provided by the health care team during the last few months of a person’s life and when experiencing an end-stage illness that is life threatening or steadily progressing toward death. It is an integrated, patient/family-centered, and compassionate approach to care that is guided by a sense of respect for one’s dignity and comfort. It also addresses the unique needs of patients and their families at a time when life-prolonging interventions are no longer considered appropriate or effective.

C. Good death—Death that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients and their families, and in accordance with the patient’s and family’s wishes. It is care that is considered reasonable and consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards of care.

D. Health care proxy—A legal document that directs whom the health care provider/agency should contact for approval/consent of treatment decisions or options when the patient is no longer deemed competent to decide for himself or herself.

E. Hospice care—A model of quality and compassionate care at the end of life. It focuses on caring not curing, and the belief that each person has the right to die pain free and with dignity.

F. Palliative care—A health care approach that seeks to provide the best possible quality of life for people with chronically progressive or lifethreatening illnesses and in accordance with their particular values, beliefs, needs, and preferences.

G. Patient self-determination—Making treatment decisions, such as designating a health care proxy, establishing advance directives, deciding to refuse or discontinue care, and choosing to not be resuscitated or to withdraw nutritional support.

H. Primary palliative and hospice care level—Palliative and hospice care provided by the same health care team responsible for routine care of the patient’s life-threatening illness.

I. Specialty palliative and hospice care level—Palliative and hospice care provided by a health care team of appropriately trained and credentialed professionals, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and others.

▪ PALLIATIVE CARE

A. Palliative care is both a philosophy of care and an organized, highly structured care delivery system.

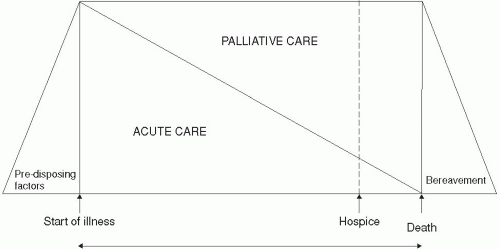

B. Palliative care can be delivered by a multidisciplinary team concurrently with life-prolonging measures or as the main focus of care. It may begin

at the time a life-threatening or debilitating illness or injury is diagnosed, and continues through care or until after the patient’s death—that is, into the family’s bereavement period.

at the time a life-threatening or debilitating illness or injury is diagnosed, and continues through care or until after the patient’s death—that is, into the family’s bereavement period.

C. Palliative care is best defined as an interdisciplinary care that aims to relieve suffering and improve quality of life for patients with advanced illness and their families. It is offered simultaneously with all other appropriate medical treatment (see Fig. 7-1) (Meier, 2006).

D. Palliative care involves addressing the physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of patients and their families. It facilitates the patient’s autonomy, self-determination, access to critical information, and right to choice of care and treatment options.

E. Palliative care programs aim to improve or optimize the quality of life for patients with advanced illness in collaboration with their families and caregivers. This is achieved by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering.

F. The delivery of palliative care may occur in the setting of the administration of life-prolonging therapy or in a setting where the sole aim is amelioration of suffering.

G. Palliative care may require end-of-life care and services. The delivery of such services requires the involvement of health care professionals who possess specialized skills, knowledge, and competencies in caring for the terminally ill at the end stage of illness or when nearing death.

▪ HOSPICE CARE

A. Hospice care is a service delivery system that provides comprehensive care for patients suffering from a terminal illness and who have a limited life expectancy—generally 6 months or less if the disease follows its usual course.

The hospice population includes a subset of palliative care patients who have entered the end-of-life stage of their illness.

The care is patient centered and extends to the care of the family unit as well.

Family is defined by the patient.

Care requires comprehensive biomedical, psychosocial, and spiritual support, especially during the final stage of illness.

Hospice care supports family members coping with the complex consequences of illness as death nears, as well as post-death during the bereavement phase.

B. The hospice benefit is designed to cover the needs of a patient with respect to physician services, medications, durable medical equipment, nursing services, home health aid, social services, and spiritual care. Essentially, costs are related to the services required to care for the terminal diagnosis for which a patient is on hospice care.

C. Home is considered the patient’s residence and is not necessarily limited to a “typical” home setting. Home could also be a nursing home, jail or prison, hospice residence, or assisted living facility.

D. Hospice statistics continue to demonstrate that one of the barriers to receiving good hospice care is late referrals.

Patients are often not referred until the last few days or weeks of life as opposed to earlier when they would be able to benefit more fully from the services that are offered to them and their family.

The reasons for late referrals are multifactorial and include but are not limited to:

Physicians’ overly optimistic views of their patients’ prognoses

Inability of physicians to provide bad news to patients and their families/caregivers

Inability of physicians to discuss hospice as an option for care at the end of life (Hakim, Teno, Harrell et al., 1996; Hofmann, Wenger, Davis et al., 1997).

E. Studies that have looked at the quality of life of patients on hospice care have continuously demonstrated improvement in their overall condition.

F. With the improvement in the level of education of case management staff, including case managers, about the barriers to hospice care, it is hoped that better communication, collaboration, and coordination of care will move patients upstream early for palliative and hospice referrals.

G. The barrier most commonly encountered by health care providers, including case managers, is identifying patients with chronic illnesses that have entered into the end-stage phase of the disease trajectory.

Patients with cancer are more easily identifiable.

Patients with end-stage illnesses other than cancer are not easily recognized.

TABLE 7-1 Karnofsky Performance Status Scale

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|