On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

understand how to anticipate and, to some extent, avoid difficulties encountered at CS

appreciate the techniques that can help you cope with such difficulties.

Introduction

CS is the process of delivering a baby abdominally. It may be required on fetal grounds or on maternal grounds. Rates vary enormously, not only between countries but also between hospitals, but trends are generally increasing worldwide. In the UK, the CS rate for 2011–12 was 25%, according to the NHS maternity statistics report. This reflects the fact that, in most developed countries, around one in four women will deliver by CS. The caesarean rate continues to rise in developing countries as well, and has now reached 50% in China. CS has become one of the most (if not the most) commonly performed operations in the world.

The decision to perform a CS can be obvious in some circumstances, while in others it can be extremely difficult. This decision-making skill in terms of timing and mode of delivery is acquired over many years, with experience and clinical judgement. CS should never be seen as the easy option. All risks of CS, as opposed to those of proceeding with an attempt at labour and vaginal delivery, should be considered and balanced in each individual circumstance, taking into account both maternal and fetal interests.

This chapter is not designed to list the indications or arguments for CS, nor to give intricate detail into surgical technique, but rather to highlight the difficulties that can be encountered (both anticipated and unexpected) and to suggest ways in which they can be predicted, recognised and dealt with in the acute situation.

Prerequisites for CS

The woman should understand the indications for the procedure and agree to it, giving written informed consent.

Anaesthesia should be achieved (either regional or general).

The patient or operating table should be tilted laterally 30°, to minimise aortocaval compression during the procedure.

The bladder should be kept empty with a urethral catheter.

Someone should be in attendance that is capable of performing neonatal resuscitation.

The operator must have appropriate experience and competence.

Prophylactic antibiotics and appropriate thromboprophylaxis should be used.

Blood may need to be grouped and saved or crossmatched, depending on the clinical situation at hand and local arrangements.

Anticipating problems in specific circumstances

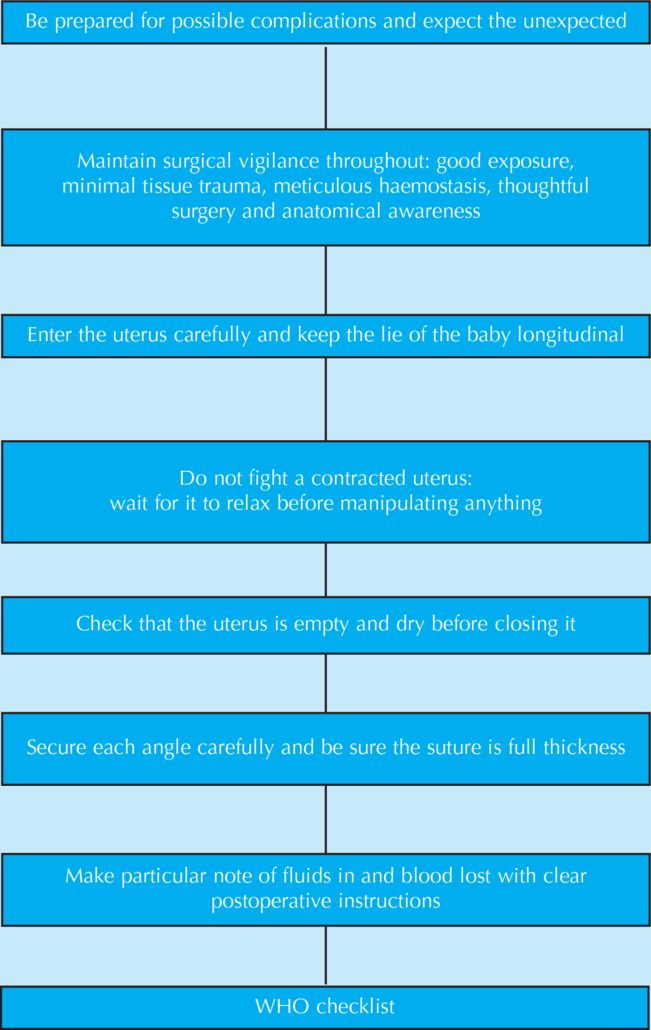

Before embarking on any surgery, rehearse the principles of good and safe surgical technique:

maintain a sterile operative field

achieve good exposure with an appropriate incision

keep tissue handling to a minimum and avoid unnecessary dissection and trauma

treat the tissues with respect

achieve meticulous haemostasis

while operating, positively consider and avoid the common problems that could turn a straightforward procedure into a complex one.

Skin incision

A low transverse skin incision is usually adequate for all uterine incisions except the true high classic incision extending up to the fundus. Make sure that the incision used affords adequate access.

Entry

Entry to the peritoneal cavity should be careful and safe. Special care is needed if there has been previous surgery (bowel can be tethered or bladder can be high).

The operator and the assistant should avoid hooking fingers under the rectus muscle (between the rectus muscle and the peritoneum), as this can seriously threaten the inferior epigastric vascular bundle.

Before extending the peritoneal incision, check there are no adhesions hidden from view; the tearing that is done at this stage of surgery can be frighteningly vicious – be gentle.

Assess the lower uterine segment

The uterovesical peritoneal reflexion identifies the upper limit of the lower uterine segment, and is invaluable in planning the uterine incision in difficult circumstances, such as CS at full dilatation, preterm delivery or abnormal lie situations.

Always check the degree of uterine rotation, and correct it, or allow for it, prior to making the uterine incision to reduce the likelihood of angle extension into the broad ligament.

Exposure

Make sure the peritoneum is reflected well clear of the proposed angles of the uterine incision, as failure to do this can compromise access, haemostasis and closure of the angles if they have extended during delivery.

Uterine incision

Do not do this until you have either checked and confirmed that there is a presenting part in the pelvis, or you have felt for the fetal lie and made a plan with your assistant regarding how to conduct the delivery.

In making the uterine incision, always try to leave membranes intact, as this will make it less likely that you will cut the baby (the membranes can then be carefully nicked just prior to delivery).

Remember that the thicker the uterine segment (preterm, placenta praevia, a high presenting part or an abnormal lie) the less space it affords you in terms of access to the baby – make sure the incision is big enough.

Be careful during this stage of the surgery to get your assistant to keep the lie of the baby longitudinal – this is especially important if the lower segment is poorly formed or full of fibroid or placenta – the last thing you need in this difficult situation with compromised space is for the baby to drift off into an oblique or transverse lie.

Delivery

At CS, the baby’s head delivers into the wound in the occipitotransverse position by lateral flexion. This procedure should be conducted gently and slowly to avoid trauma to and extension of the uterine angles.

Fundal pressure during the delivery should be sustained and should follow the distal end of the fetus on its way out (like squeezing toothpaste from a tube).

Placenta

While the placenta is attached, the placental site will not bleed and there is no need to hurry this process. Wait for separation to occur rather than precipitating a problem. If there is bleeding then Green-Armytage clamps can be placed on the bleeding sinuses or angles as needed.

Check that all placenta and membranes have been removed.

Check the patency of the internal cervical os and that it is not covered with membrane.

Closure of uterus

Both uterine angles need to be secured carefully and accurately, with each stitch passing full thickness into the uterine cavity; failure to achieve this full thickness can leave a bleeding vessel within the cavity, which will remain hidden from the surgeon’s view and produce vaginal bleeding later.

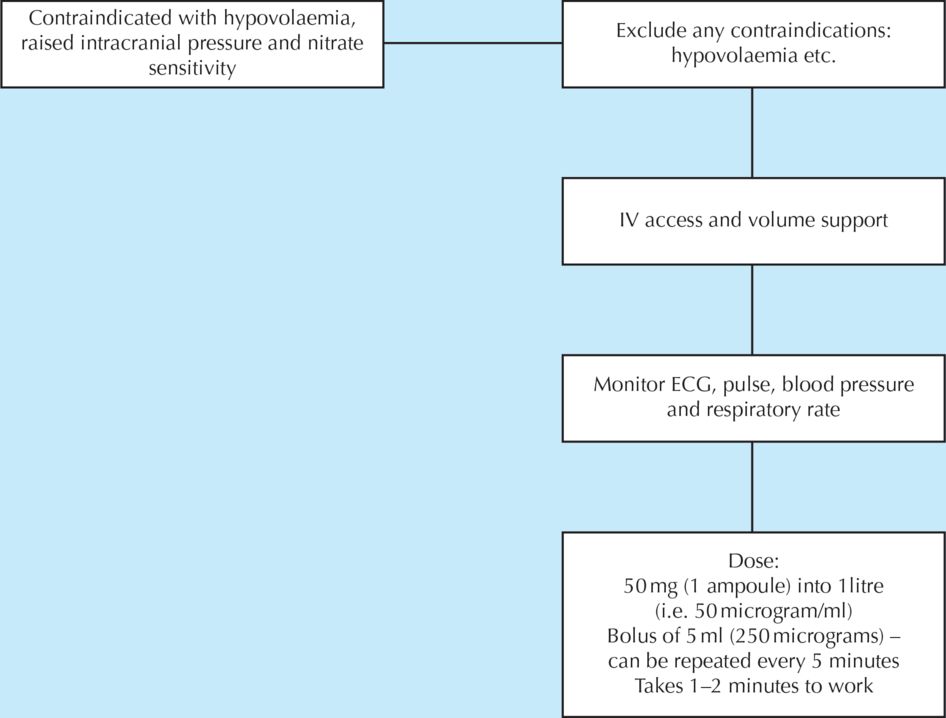

If there are placental bed bleeders (commonly seen with placenta praevia), then attention should be given to these before closing the uterus, as once closed such bleeding is hidden from the surgeon’s view. These can be dealt with by systemic uterotonics but may also need an under-running suture or a local injection of uterotonics (e.g. a solution of Syntocinon 10 units diluted in 20 ml physiological saline). Persistent placental bed bleeding can also be dealt with using tamponade with a balloon catheter, such as a Rusch or Cook-Bakri balloon, once the uterus is closed.

The uterus should routinely be closed in a double layer suture (a single layer has a higher rate of future dehiscence and rupture). Occasionally, the lower segment is so thin that a single layer is all that is possible.

Haemostasis

Once the uterus is closed, the suture line and both angles should be checked for haemostasis while exposed without tension.

Great care should then be taken checking the peritoneal edges, the subrectus space and, if exposed, the inferior epigastric bundles for haemostasis before the sheath is closed. Where the visceral peritoneum is not closed, this process of haemostasis is even more vital than previously as there is no tamponade effect on bleeding vessels in this layer, and massive obstetric haemorrhage occurring due to bleeding from this site has been reported.

Drains

Anyone who claims never to need drains because they ‘never close if everything isn’t perfectly dry’ paints an enviable but rather naïve picture. While haemostasis should always be the aim, occasionally drains can be useful if there has been extremely difficult surgery with extensive dissection and raw surfaces, or if there is likely to be a postpartum clotting problem (fulminating pre-eclampsia, HELLP, DIC, sepsis).

Any drain placed within the peritoneal cavity should be soft and large bore (such as the Robinson drain) and not suctioned. If a suctioned drain is placed in the rectus space then the peritoneum should be closed (otherwise the drain is effectively intra-abdominal).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree