Chapter 68 Burn Injuries

Epidemiology

Approximately 1.2 million people in the USA require medical care for burn injuries each year, with 51,000 requiring hospitalization. Approximately 30-40% of these patients are younger than 15 yr, with an average age of 32 mo. Fires are a major cause of mortality in children, accounting for up to 34% of fatal injuries in those younger than 16 yr. Scald burns account for 85% of total injuries and are most prevalent in children younger than 4 yr. Although the incidence of hot water scalding has been reduced by legislation requiring new water heaters to be preset at 120°F, scald injury remains the leading cause of hospitalization for burns. Steam inhalation used as a home remedy to treat respiratory infections is another potential cause of burns. Flame burns account for 13%; the remaining are electrical and chemical burns. Clothing ignition events have declined since passage of the Federal Flammable Fabric Act requiring sleepwear to be flame-retardant; however, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission has voted to relax the existing children’s sleepwear flammability standard. Approximately 18% of burns are the result of child abuse (usually scalds), making it important to assess the pattern and site of injury and their consistency with the patient history (Chapter 37). Friction burns from treadmills are also a problem. Hands are the most commonly injured sites, with deep 2nd-degree friction injury sometimes associated with fractures of the fingers. Anoxia, not the actual burn, is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in house fires.

Review of the history usually shows a common pattern: scald burns to the side of the face, neck, and arm if liquid is pulled from a table or stove; burns in the pant leg area if clothing ignites; burns in a splash pattern from cooking; and burns on the palm of the hand from contact with a hot stove. However, “glove or stocking” burns of the hands and feet, single-area deep burns on the trunk, buttocks, or back, and small, full-thickness burns (cigarette burns) in young children should raise the suspicion of child abuse (Chapter 37).

Prevention

The aim of burn prevention is a continuing reduction in the number of serious burn injuries (Table 68-1). Effective first aid and triage can decrease both the extent (area) and the severity (depth) of injuries. The use of flame-retardant clothing and smoke detectors, control of hot water temperature (thermostat settings) within buildings, and prohibition of cigarette smoking have been partially successful in reducing the incidence of burn injuries. Treatment of children with significant burn injuries in dedicated burn centers facilitates medically effective care, improves survival, and leads to greater cost efficiency. Survival of at least 80% of patients with burns of 90% of the body surface area (BSA) is possible; the overall survival rate of children with burns of all sizes is 99%. Death is more likely in children with irreversible anoxic brain injury sustained at the time of the burn.

Acute Care, Resuscitation, and Assessment

Indications for Admission

Burns covering >10-15% of total BSA, burns associated with smoke inhalation, burns resulting from high-tension (voltage) electrical injuries, and burns associated with suspected child abuse or neglect should be treated as emergencies, and the child hospitalized (Table 68-2). Small 1st- and 2nd-degree burns of the hands, feet, face, perineum, and joint surfaces also require admission if close follow-up care is difficult to provide. Children who have been in enclosed-space fires and those who have face and neck burns should be hospitalized for at least 24 hr for observation for signs of central nervous system (CNS) effects of anoxia from carbon monoxide poisoning and pulmonary effects from smoke inhalation.

First Aid Measures

Acute care should include the following measures:

Emergency Care

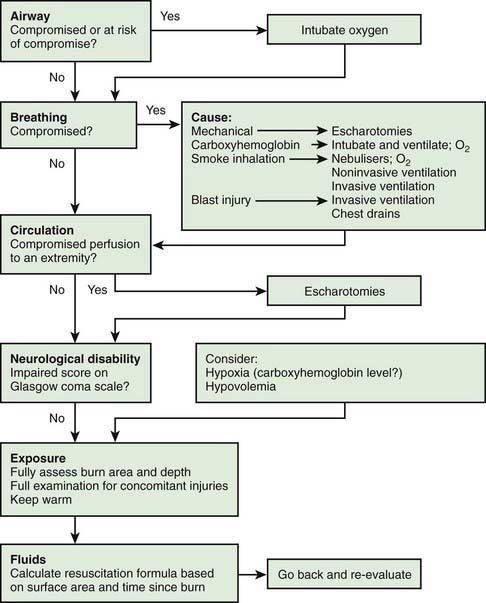

Life support measures are as follows (Table 68-3):

Classification of Burns

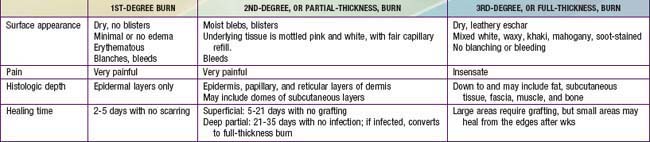

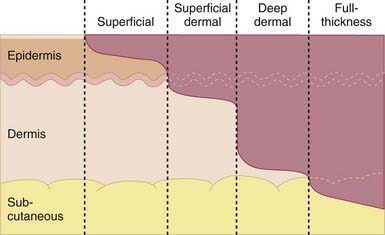

Proper triage and treatment of burn injury require assessment of the extent and depth of the injury (Table 68-4 and Fig. 68-2). 1st-degree burns involve only the epidermis and are characterized by swelling, erythema, and pain (similar to mild sunburn). Tissue damage is usually minimal, and there is no blistering. Pain resolves in 48-72 hr; in a small percentage of patients, the damaged epithelium peels off, leaving no residual scars.

Figure 68-2 Diagram of the different burn depths.

(From Hettiaratchy S, Papini R: Initial management of a major burn II: assessment and resuscitation, BMJ 329:101–103, 2004.)

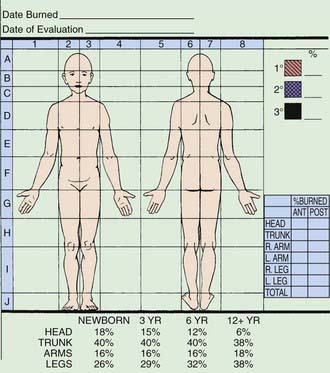

Estimation of Body Surface Area for a Burn

Appropriate burn charts for different childhood age groups should be used to accurately estimate the extent of BSA burned. The volume of fluid needed in resuscitation is calculated from the estimation of the extent and depth of burn surface. Mortality and morbidity also depend on the extent and depth of the burn. The variable growth rate of the head and extremities throughout childhood makes it necessary to use BSA charts, such as that modified by Lund and Brower or the chart used at the Shriners Hospital for Children in Boston (Fig. 68-3). The rule of nines used in adults may be used only in children older than 14 yr or as a very rough estimate to institute therapy before transfer to a burn center. In small burns, <10% of BSA, the rule of palm may be used, especially in outpatient settings: The area from the wrist crease to the finger crease (the palm) in the child equals 1% of the child’s BSA.

Treatment

Outpatient Management of Minor Burns

A patient with 1st- and 2nd-degree burns of <10% of BSA may be treated on an outpatient basis unless family support is judged inadequate or there are issues of child neglect or abuse. These outpatients do not require a tetanus booster (unless not truly immunized) or prophylactic penicillin therapy. Blisters should be left intact and dressed with bacitracin or silver sulfadiazine cream (Silvadene). Dressings should be changed once daily, after the wound is washed with lukewarm water to remove any cream left from the previous application. Very small wounds, especially those on the face, may be treated with bacitracin ointment and left open. Debridement of the devitalized skin is indicated when the blisters rupture. A variety of wound dressings/wound membranes are available (e.g., AQUACEL Ag dressing [ConvaTec USA, Skillman, NJ] in a soft feltlike material impregnated with silver ion) may be applied to 2nd-degree burns and wrapped with a dry sterile dressing; similar wound membranes provide pain control, prevention of wound desiccation, and reduction in wound colonization (Table 68-5). These dressings are usually kept on for 7-10 days but are checked twice a week.

Table 68-5 PARTIAL LISTING OF SOME COMMONLY USED WOUND MEMBRANES—SELECTED CHARACTERISTICS

| MEMBRANE | CHARACTERISTIC(S) |

|---|---|

| Porcine xenograft | |

| Biobrane | |

| Acticoat | Nonadherent dressing that delivers silver |

| AQUACEL-Ag | Absorptive hydro-fiber that delivers silver |

| Various semipermeable membranes | Provide vapor and bacterial barrier |

| Various hydrocolloid dressings | |

| Various impregnated gauzes | Provide barrier while allowing drainage |

The depth of scald injuries is difficult to assess early; conservative treatment is appropriate initially, with the depth of the area involved determined before grafting is attempted (Fig. 68-4). This approach obviates the risk of anesthesia and unnecessary grafting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree