Breech Delivery

Of the factors associated with breech presentation (Table 8-1), the most important is gestational age. For example, Scheer and Nubar (1976) reported that breech presentation occurred in approximately one-third of pregnancies at 21-24 weeks, and 14 percent of those occurred at 29-32 weeks; by term, however, only 3-4 percent of all singleton deliveries are associated with a breech presentation. Previous breech presentation is also a significant risk factor. In a review by Albrechtsen and colleagues (1998a), the odds ratio of recurrent breech presentation increased from 4.32 (95 percent CI 4.08–4.59) after one previous breech delivery to 28.1 (95 percent CI 12.2-64.8) after three previous breech deliveries.

TABLE 8-1. Factors Associated with Breech Presentation

Great parity

Multiple fetuses

Hydramnios

Oligohydramnos

Uterine anomalies

Pelvic tumors

Anomalous fetus

Previous breech presentation

There are three basic types of breech presentation. With the frank breech presentation, the fetal legs are flexed at the hips and extended at the knees (Fig. 8-1). With the complete breech, the legs are flexed at the hips and one or both knees are also flexed (Fig. 8-2). With the incomplete or footling breech presentation, one or both feet or knees lie below the fetal buttocks as the main presenting part (Fig. 8-3). This latter presentation is especially at risk for prolapse of the umbilical cord.

FIGURE 8-1. Frank breech. The hips are flexed and the knees are extended with the feet lying near the infant’s face.

FIGURE 8-2. Longitudinal lie. Complete breech presentation: both the hips and the knees are flexed and the feet present with the buttocks. This attitude is easily recognized by vaginal examination after the cervix has dilated to 4-5 cm.

FIGURE 8-3. Single-footling breech presentation in labor with membranes intact. Note possibility of umbilical cord accident at any instant, especially after rupture of membranes.

COMPLICATIONS

Both mother and fetus are at greater risk for complications with breech presentation as compared with cephalic presentation. These risks include an increase in perinatal morbidity and mortality, prolapsed umbilical cord, placenta previa, congenital anomalies, and cesarean delivery. In a comparison of indications for cesarean between 1985 and 1994, Gregory and colleagues (1998) reported a significant increase in cesareans performed for dystocia and breech presentations in 1994.

FETAL RISKS

There is little question that the prognosis for the fetus presenting as a breech either in labor or at delivery is worse than the prognosis for a fetus in cephalic presentation. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in these fetuses is usually secondary to either prematurity or congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies are two to three times greater for the fetus in breech presentation as compared to those in cephalic presentation (Brenner and colleagues, 1974). Perinatal mortality is also three to four times greater in breech compared to cephalic presentations. Gimovsky and Paul (1982) reported a mortality rate of 8.5 percent for the fetus in breech presentation and 2.2 percent for those in cephalic presentation. The increased mortality rate for the fetus presenting as a breech was seen despite a 75 percent cesarean delivery rate. In a national, population-based study from Norway, Albrechtsen and colleagues (1998b) reported that the odds ratio for perinatal mortality was 4.3 for breech versus nonbreech presentation, and 5.4 for vaginal versus cesarean delivery. These authors very aptly pointed out that this increased mortality in breech presentation was due in part to other risk factors for mortality associated with breech presentation.

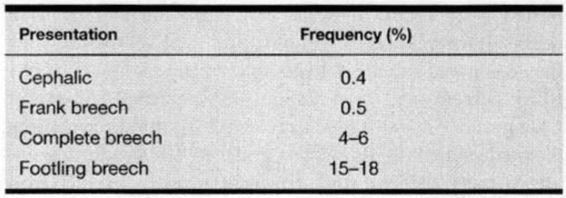

With the exception of the frank breech, cord prolapse increases significantly with breech presentation compared to cephalic presentation (Collea and coworkers, 1978; Barrett, 1991). Table 8-2 summarizes the risk of cord prolapse according to presentation.

TABLE 8-2. Frequency of Cord Prolapse

Persistent breech presentation also may be a predictor of a neurologically abnormal fetus. In an analysis of more than 57,000 pregnancies, Schutte and associates (1985) concluded, “it is possible that breech presentation is not coincidental but is a consequence of poor fetal quality, in which case medical intervention is unlikely to reduce the perinatal mortality associated with breech presentation to the level associated with vertex presentation.” This concept is further supported by the findings of Hytten (1982) and Susuki (1985). Nelson and Ellenberg (1986), as well as Torfs and associates (1990), found breech presentation to be a risk factor for cerebral palsy regardless of delivery route.

Breech presentation itself, rather than method of delivery, may help explain other reported complications. For example, torticollis that has often been associated with “traumatic vaginal breech delivery” has recently been reported in a newborn of a nonlaboring woman who underwent an elective cesarean delivery for breech presentation (Sherer, 1996). Cheng and colleagues (1999), in a study of 510 cases of sternomastoid pseudotumor and congenital torticollis, reported a high correlation with breech presentation and assisted delivery.

MATERNAL RISKS

The major maternal complications associated with breech presentation are those coincident with cesarean delivery. Although maternal mortality is rare, death is significantly more common with cesarean section than is death following vaginal delivery. Maternal morbidity is also significantly increased with operative delivery. Weiner (1992) has estimated that routine cesarean delivery for all breech presentations in 1990 cost society almost $1.5 billion. Delivery of only 50 percent of breech presentation vaginally would save more than $700 million annually. In the year 2001, these estimates are no doubt much higher.

VAGINAL DELIVERY VERSUS CESAREAN DELIVERY

Over the last 35 years or so, the equivalent of one professional life span for an obstetrician, there has been a dramatic change in opinion regarding the most appropriate route of delivery for the persistent breech presentation. In contemporary obstetric practice, the vast majority of fetuses presenting as breeches are delivered via cesarean delivery (ACOG, 1986). Green and associates (1982) reported that the cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation had increased from 22 percent in the decade 1963 through 1973 to 94 percent by 1979. Breech presentations now account for approximately 15 percent of all cesarean deliveries (Weiner, 1992). The major reason for the high cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation is the belief that avoiding vaginal delivery can reduce both perinatal mortality and morbidity. A second factor is the inadequate instruction and training in vaginal breech delivery received by the majority of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Furthermore, even obstetricians proficient at vaginal breech delivery at the completion of residency are unlikely to encounter a significant number of breeches in practice. For example, Moore (1988) has estimated that the “average” practitioner of 240 deliveries per year will encounter only 10 breeches per year, and that of these 10 breeches, only 2 would be candidates for a trial of labor.

Has the increase in cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation resulted in an improvement in fetal outcome? In select cases, such as birthweights of 500-1000 g, who are at highest risk for entrapment of the fetal head, the answer may be yes. A more clinically relevant question is whether cesarean delivery improves outcome for all breech presentations (eg, footling vs. frank presentation) at all gestational ages (eg, term vs. preterm). Additionally, most busy delivery services occasionally have patients who present with a partially or mostly delivered fetus in breech presentation at a stage when it is too late to proceed with an abdominal delivery. In a review for the Cochrane Database, Hofmeyr and Hannah (2000) concluded that, “there is not enough evidence to evaluate the use of a policy of planned caesarean section for breech presentation.” They also referred to the Canadian trial which had not been published at the time of their review (Hannah and colleagues, 2000).

THE TERM BREECH FETUS

Collea and coworkers (1980) and Gimovsky and associates (1983) reported the results of prospective studies regarding the method of delivery for the term breech presentation. In the 1980 report, 115 of 208 infants in the frank breech presentation were randomized to a trial of labor. Following x-ray pelvimetry, only 60 women were judged to be candidates for vaginal delivery, and of these candidates, 49 (82 percent) delivered vaginally. There were two transient brachial plexus injuries in the vaginal delivery group. Maternal morbidity was significantly higher in the 148 women who underwent cesarean delivery. In 105 women at term with a nonfrank breech presentation, Gimovsky and colleagues (1983) reported 31 of 70 (44 percent) patients randomized to a trial of labor following x-ray pelvimetry delivered vaginally. Neonatal morbidity in the vaginal and cesarean groups was similar. The one neonatal death occurred in the cesarean group.

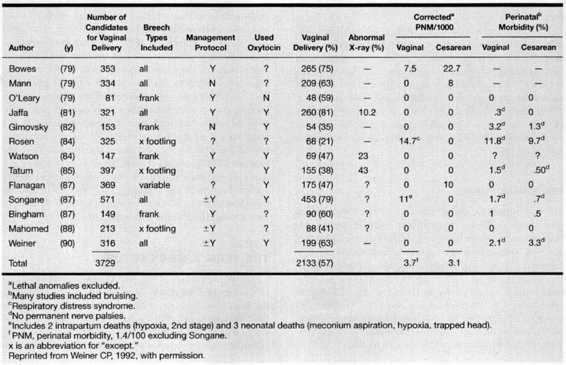

In a review of the literature regarding vaginal breech delivery at term, Weiner (1992) found that in 13 retrospective studies of 3729 breeches, 2133 (57 percent) were delivered vaginally. The corrected perinatal mortality was 3.1/1000 for neonates delivered via cesarean delivery as compared to 3.7/1000 for neonates delivered vaginally (Table 8-3). In a review of 1240 singleton breech infants (term and preterm) from the California Kaiser Permanente Program (term and preterm), Crough-Minihane and associates (1990) found that 75 percent were delivered by cesarean and 25 percent were delivered vaginally. There was no significant association between route of delivery and frequency of head trauma, newborn seizures, mental retardation, or cerebral palsy.

TABLE 8-3. Vaginal Breech Deliveries ≥2000 g and ≤3900 g (or Greater Than 35 w) Retrospective

In contrast, Thorpe-Beeston and colleagues (1992) reported a significant increase in intrapartum and neonatal deaths in term breeches without congenital anomalies when they compared vaginal delivery to cesarean section [8 of 961 (0.83 percent) vs. 1 of 2486 (0.03 percent)]. Moreover Cheng and Hannah (1993) reviewed 24 studies regarding planned vaginal versus elective cesarean delivery for the singleton term breech. Both perinatal mortality (odds ratio 3.86; 95 percent CI 2.2-6.7) and neonatal morbidity (odds ratio 3.96; 95 percent CI 2.76-5.67) were higher for the planned vaginal delivery groups. However, as the authors pointed out, “because of selection bias in the majority of studies, differences in outcome may be due to factors other than the planned method of delivery.”

A recently published multicenter randomized trial (Hannah and colleagues, 2000) addresses the controversies regarding whether perinatal morbidity/mortality is increased by vaginal delivery and whether routine cesarean delivery is indicated or recommended for all breeches (Schiff, 1996; Koo, 1998; Albrechtsen, 1997; Daniel, 1998; Roman, 1998; Irion, 1998; and their many colleagues). This trial by the Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group was done in 121 centers from 26 countries and involved more than 2000 women with a frank or incomplete breech presentation. There were 1041 women randomized to the planned cesarean delivery group and 1042 assigned to the planned vaginal delivery group. Ninety percent of the former were delivered by cesarean, and approximately 57 percent of the latter delivered vaginally. Perinatal/neonatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity were higher in the planned vaginal delivery group than for the planned cesarean delivery group (5 percent vs. 1.6 percent). The relative risk for these adverse outcomes in the planned cesarean group was 0.33 (95 percent CI 0.19-0.56). There were no significant differences (p = 0.35) in maternal mortality or serious morbidity when comparing the cesarean group (3.9 percent) with the vaginal group (3.2 percent).

THE PRETERM BREECH FETUS

There may be significant disparity between the size of the fetal head and the buttocks in the premature infant. In such cases, the body of the fetus may pass through the cervix easily while the head may become trapped. There are no large randomized prospective studies addressing delivery of premature breech. However, several retrospective studies have suggested improved neonatal outcome, as measured by perinatal mortality, developmental abnormalities, and intracranial hemorrhage with cesarean delivery of preterm breech fetuses weighing less than 1500-2000 g (Ingemarsson, 1978; Westgren, 1985a,b; Morales, 1986; Bodmer, 1986). Although preterm fetuses in this weight range most commonly undergo cesarean section in the United States, the value of operative delivery for these infants is not universally accepted (Cox, 1982; Effer, 1983).

PELVIMETRY

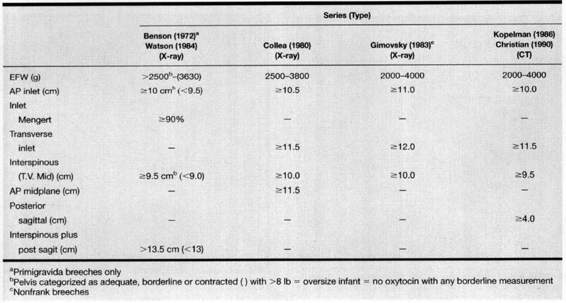

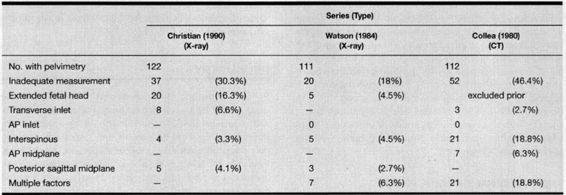

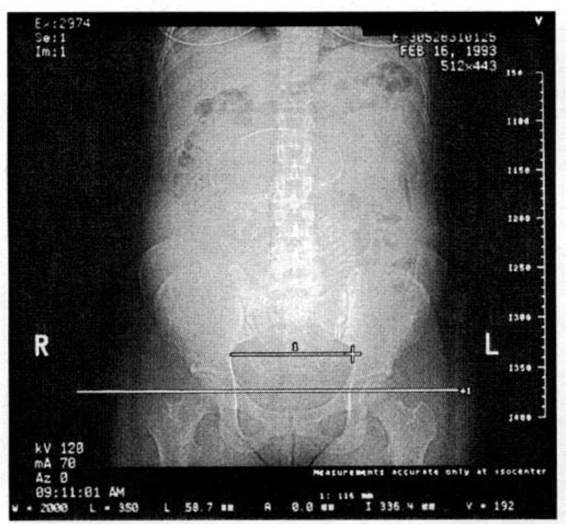

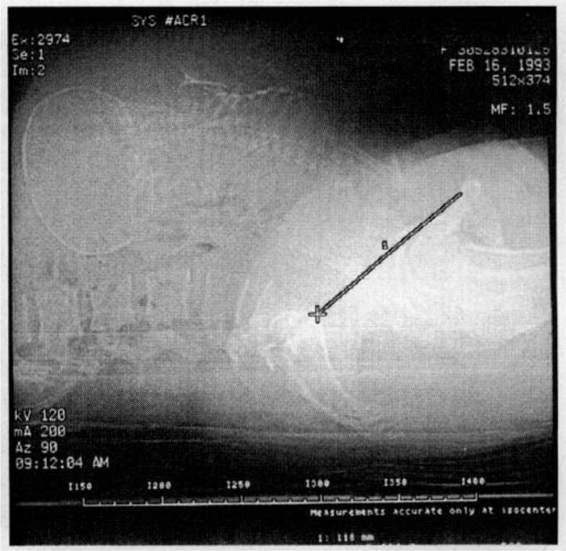

Some obstetricians recommend x-ray pelvimetry for the management of breech presentation. For example, Ridley and associates (1982) reported that the cesarean section rates were 40 percent, 61 percent, and 89 percent when the pelvis was adequate, marginal, or inadequate, respectively. Protocols for selected breech delivery are summarized in Tables 8-4 and 8-5. In a study from Tel Aviv, Israel, Fait and colleagues concluded that x-ray pelvimetry in nulliparae does not improve neonatal outcome. Because of the relatively high-dose exposure from conventional x-ray pelvimetry (1-5 rads), computed tomography (CT) is now recommended (Table 8-6). With CT pelvimetry, exposure may be as low as 250 mrad (Moore and Shearer, 1989). Collea and associates (1980) defined an adequate pelvic inlet by plain film pelvimetry as a transverse diameter of 11.5 cm and an anterior-posterior diameter of 10.5 cm. For the midpelvis, the bispinous diameter would be 10.5 cm and the anterior-posterior diameter should be 11 cm or greater. Examples of CT pelvimetry are shown in Figures 8-4 through 8-7.

TABLE 8-4. Breech Pelvimetry Protocols

TABLE 8-5. Reasons for Exclusion from Trial of Labor in Breech Presentation Using Pelvimetry

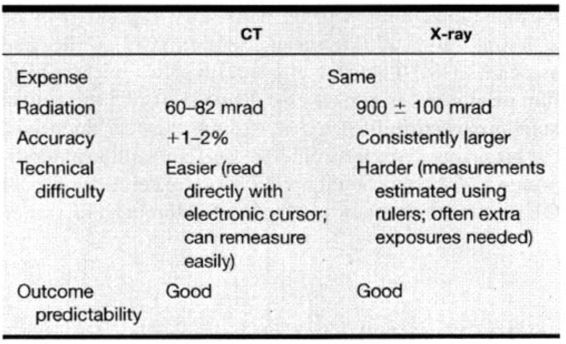

TABLE 8-6. CT vs. Conventional X-ray Pelvimetry

FIGURE 8-4. Anteroposterior digital radiograph used to obtain fetogram. Frank breech, head military transverse diameter of the inlet, and level (foveae) for the axial section.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree