FIGURE 28-1 Prevalence of breech presentation by gestational age at delivery in 58,842 singleton pregnancies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospitals 1991 to 2006. (Data courtesy of Dr. John Hauth and Ms. Sue Cliver.)

Current obstetrical thinking regarding vaginal delivery of the breech fetus has been tremendously influenced by results reported from the Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group (Hannah, 2000). This trial included 1041 women randomly assigned to planned cesarean and 1042 to planned vaginal delivery. In the planned vaginal delivery group, 57 percent were actually delivered vaginally. Planned cesarean delivery was associated with a lower risk of perinatal mortality compared with planned vaginal delivery—3 per 1000 versus 13 per 1000. Cesarean delivery was also associated with a lower risk of “serious” neonatal morbidity—1.4 versus 3.8 percent.

The reaction to these findings by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2001) resulted in an abrupt decline in the rate of attempted vaginal breech deliveries. Since those times, however, a more moderate plan was reached for management of breech delivery.

Critics of the Term Breech Trial emphasized that most of the outcomes included in the “serious” neonatal morbidity composite did not actually portend long-term disability. Moreover, as data from countries with low perinatal mortality rates became available, they showed infrequent perinatal deaths, and rates did not differ significantly between mode-of-delivery groups. Also, only nulliparas were included in the Term Breech Trial, and fewer than 10 percent underwent radiological pelvimetry. And last, the 2-year outcomes for children born during the original multicenter trial showed that planned cesarean delivery was not associated with a reduction in the rate of death or developmental delay (Whyte, 2004). Some of the large studies reporting the safety and risks of vaginal delivery for the term breech singleton are discussed further on page 561.

These findings prompted the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b) to modify its stance on breech presentation, and it currently recommends that “the decision regarding the mode of delivery should depend on the experience of the health care provider” and that “planned vaginal delivery of a term singleton breech fetus may be reasonable under hospital-specific protocol guidelines.” This has been echoed by other obstetrical organizations (Carbonne, 2001; Kotaska, 2009; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2009).

CLASSIFICATION OF BREECH PRESENTATIONS

The varying relations between the lower extremities and buttocks of breech fetuses form the categories of frank, complete, and incomplete breech presentations. With a frank breech presentation, the lower extremities are flexed at the hips and extended at the knees, and thus the feet lie in close proximity to the head (Fig. 28-2). A complete breech differs in that one or both knees are flexed (Fig. 28-3). With incomplete breech presentation, one or both hips are not flexed, and one or both feet or knees lie below the breech, such that a foot or knee is lowermost in the birth canal (Fig. 28-4). A footling breech is an incomplete breech with one or both feet below the breech.

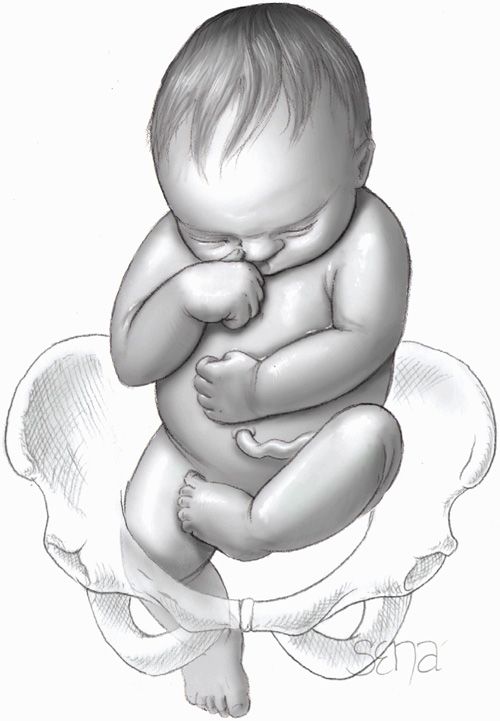

FIGURE 28-2 Frank breech presentation.

FIGURE 28-3 Complete breech presentation.

FIGURE 28-4 Incomplete breech presentation.

In perhaps 5 percent of term breech fetuses, the head may be in extreme hyperextension. These presentations have been referred to as the stargazer fetus, and in Britain as the flying foetus. With such hyperextension, vaginal delivery may result in injury to the cervical spinal cord. Thus, if present after labor has begun, this is an indication for cesarean delivery (Svenningsen, 1985).

DIAGNOSIS

Risk Factors

Risk Factors

Understanding the clinical settings that predispose to breech presentation can aid early recognition. Other than early gestational age, risk factors include abnormal amnionic fluid volume, multifetal gestation, hydrocephaly, anencephaly, uterine anomalies, placenta previa, fundal placental implantation, pelvic tumors, high parity with uterine relaxation, and prior breech delivery. Specifically, following one breech delivery, the recurrence rate for a second pregnancy with breech presentation was nearly 10 percent, and that for a subsequent third pregnancy was 27 percent (Ford, 2010). Prior cesarean delivery has also been described by some to increase twofold the incidence of breech presentation (Kalogiannidis, 2010; Vendittelli, 2008). Last, smoking may be a modifiable cause of this presentation (Rayl, 1996; Witkop, 2008).

Examination

Examination

Leopold maneuvers to ascertain fetal presentation are discussed in Chapter 22 (p. 438). With the first maneuver, the hard, round, ballottable fetal head may be found to occupy the fundus. The second maneuver indicates the back to be on one side of the abdomen and the small parts on the other. With the third maneuver, if not engaged, the breech is movable above the pelvic inlet. After engagement, the fourth maneuver shows the firm breech to be beneath the symphysis. The accuracy of this palpation varies (Lydon-Rochelle, 1993; Nassar, 2006). Thus, with suspected breech presentation—or any presentation other than cephalic—sonographic evaluation is indicated.

With a frank breech during vaginal examination, no feet are appreciated, but the fetal ischial tuberosities, sacrum, and anus are usually palpable. After further fetal descent, the external genitalia may also be distinguished. Especially when labor is prolonged, the fetal buttocks may become markedly swollen, rendering differentiation of a face and breech difficult. In some cases, the anus may be mistaken for the mouth and the ischial tuberosities for the malar eminences. With careful examination, however, the finger encounters muscular resistance with the anus, whereas the firmer, less yielding jaws are felt through the mouth. The finger, upon removal from the anus, may be stained with meconium. The mouth and malar eminences form a triangular shape, whereas the ischial tuberosities and anus lie in a straight line. With a complete breech, the feet may be felt alongside the buttocks. In footling presentations, one or both feet are inferior to the buttocks.

The fetal sacrum and its spinous processes are palpated also to establish position. As with cephalic presentations described in Chapter 22 (p. 434), fetal positions are designated as left sacrum anterior (LSA), right sacrum anterior (RSA), left sacrum posterior (LSP), right sacrum posterior (RSP), or sacrum transverse (ST) to reflect the relations of the fetal sacrum to the maternal pelvis.

ROUTE OF DELIVERY

Multiple factors aid determination of the best delivery route for a given mother-fetus pair. These include fetal characteristics, pelvic dimensions, coexistent pregnancy complications, operator experience, patient preference, and hospital capabilities.

Term and Preterm Breech Fetus

Term and Preterm Breech Fetus

Although sharing the similarity of presentation, preterm breech fetuses have distinct risks related to immaturity compared with their term breech counterparts. Accordingly, separation of term and preterm breech fetuses for discussion allows a more accurate evaluation of information.

Term Breech Fetus

Data regarding superior perinatal outcomes for planned cesarean delivery of a singleton term breech are conflicting. As described earlier (p. 558), the Term Breech Trial reported lower neonatal morbidity and mortality rates with planned cesarean delivery for breech presentation. Additional data favoring cesarean delivery comes from the World Health Organization (Lumbiganon, 2010). From their evaluation of more than 100,000 deliveries from nine participating Asian countries, they reported improved perinatal outcomes associated with planned cesarean compared with planned vaginal delivery of the term breech fetus. Other studies have evaluated neonatal outcome with cesarean delivery and also found lowered neonatal morbidity and mortality rates (Hartnack Tharin, 2011; Mailàth-Pokorny, 2009; Rietberg, 2005; Swedish Collaborative Breech Study Group, 2005).

In contrast, the Presentation et Mode d’Accouchement—which translates as presentation and mode of delivery (PREMODA)—study showed no differences in corrected neonatal mortality rates and neonatal outcomes according to delivery mode (Goffinet, 2006). This French prospective observational study involved more than 8000 women with term breech singletons. Strict criteria were used to select 2526 of these for planned vaginal delivery, and 71 percent of that group were delivered vaginally. Similarly, data from the Lille Breech Study Group in France showed no excessive morbidity in term breech singletons delivered vaginally provided strict fetal biometric and maternal pelvimetry parameters were applied (Michel, 2011). Other smaller studies also support these findings as long as guidelines are part of the selection process (Alarab, 2004; Albrechtsen, 1997; Giuliani, 2002; Toivonen, 2012). Long-term evidence in support of vaginal breech delivery comes from Eide and associates (2005). These researchers analyzed intelligence testing scores of more than 8000 men delivered breech and found no differences in intellectual performance in those delivered vaginally or by cesarean.

Despite evidence on both sides of the debate, at least in this country, rates of planned vaginal delivery attempts continue to decline (Hehir, 2012). And as predicted, the number of skilled operators able to safely select and vaginally deliver breech fetuses continues to dwindle (Chinnock, 2007). Moreover, obvious medicolegal concerns makes physician training in such deliveries difficult. In response, some institutions have developed birth simulators to improve resident competence in vaginal breech delivery (Deering, 2006; Maslovitz, 2007).

Preterm Breech Fetus

Although there are no randomized studies regarding delivery of the preterm breech fetus, planned cesarean delivery appears to confer a survival advantage. Reddy and associates (2012) reported data from an National Institutes of Health retrospective multicenter cohort study involving 208,695 deliveries between 24 and 32 weeks’ gestation. For breech fetuses within these gestational ages, attempting vaginal delivery yielded a low completion rate, and those completed were associated with higher neonatal mortality rates compared with planned cesarean delivery. Other studies have reported similar findings (Demirci, 2012; Lee, 1998; Muhuri, 2006). There are, however, a few smaller studies that describe no improved survival rate in fetuses at earlier gestational ages—24 to 29 weeks—delivered by planned cesarean (Kayem, 2008; Stohl, 2011).

There are limited data regarding any preferable delivery route for preterm breech fetuses between 32 and 37 weeks. In these cases, fetal weight rather than gestational age is likely most important. The Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) recommend that vaginal breech delivery is reasonable when the estimated fetal weight is > 2500 g (Kotaska, 2009).

Delivery Complications

Delivery Complications

Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Increased rates of maternal and perinatal morbidity can be anticipated with breech presentations. For the mother, with either cesarean or vaginal delivery, genital tract laceration can be problematic. With cesarean delivery, added stretching of the lower uterine segment by forceps or by a poorly molded fetal head can extend hysterotomy incisions. With vaginal delivery, especially with a thinned lower uterine segment, delivery of the aftercoming head through an incompletely dilated cervix or application of forceps may cause vaginal wall or cervical lacerations. Manipulations may also extend an episiotomy, create deep perineal tears, and increase infection risks. Anesthesia sufficient to induce appreciable uterine relaxation during vaginal delivery may cause uterine atony and in turn, postpartum hemorrhage. Death is a rare complication, but rates appear higher in those with planned cesarean delivery for breech presentation—a case fatality rate of 0.47 maternal deaths per 1000 births (Schutte, 2007). Last, as described in Chapter 30 (p. 588), the risks associated with vaginal breech delivery are balanced against general cesarean delivery risks, which include those associated with vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) or those with repeated cesarean hysterotomy.

Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality

Preterm delivery is a common association, and there is an increased rate of congenital anomalies. In addition, birth trauma, although uncommon, can contribute to death of the breech fetus. Importantly, these are seen both with vaginal as well as cesarean delivery. Some of the more common injuries are fractures of the humerus, clavicle, and femur (Canpolat, 2010; Matsubara, 2008). In some cases, traction may separate scapular, humeral, or femoral epiphyses.

Rare traumatic injuries may involve bony or soft tissues. Neonatal perineal tears have been reported from fetal scalp electrodes (Freud, 1993). Upper extremity paralysis—Erb or Duchenne—may follow brachial plexus stretching (Al-Qattan, 2010). When the fetus is extracted through a contracted pelvis, spoon-shaped depressions or actual fractures of the skull may result. The spinal cord may be injured or vertebra fractured if great force is employed (Vialle, 2007). Hematomas of the sternocleidomastoid muscles occasionally develop after delivery, although they usually disappear spontaneously. Last, testicular injury may follow breech delivery (Mathews, 1999). These are discussed in further detail in Chapter 33 (p. 645).

Compared with cephalic presentation, umbilical cord prolapse is more frequent with breech fetuses. Huang and coworkers (2012) analyzed 40 cases of prolapse and reported that half were associated with malpresentation or vaginal delivery of a second twin.

Some perinatal outcomes may be inherent to the breech position rather than delivery. For example, development of hip dysplasia is more common in breech compared with cephalic presentation and is unaffected by delivery mode (de Hundt, 2012; Fox, 2010; Ortiz-Neira, 2012).

Imaging Techniques

Imaging Techniques

In many fetuses—especially those that are preterm—the breech is smaller than the aftercoming head. Moreover, unlike cephalic presentations, the head of a breech-presenting fetus does not undergo appreciable molding during labor. Thus, to avoid head entrapment following delivery of the breech, pelvic dimensions should be assessed before vaginal delivery. In addition, fetal size, type of breech, and degree of neck flexion or extension should be identified. To evaluate these, several imaging techniques can be used.

Sonography

In most cases, sonographic fetal evaluation will have been performed as part of prenatal care. If not, gross fetal abnormalities, such as hydrocephaly or anencephaly, can be rapidly ascertained with sonography. This will identify many fetuses not suitable for vaginal delivery and will help to ensure that a cesarean delivery is not performed under emergency conditions for an anomalous fetus with no chance of survival.

Head flexion can usually also be determined sonographically, and for vaginal delivery, the fetal head should not be extended (Fontenot, 1997; Rojansky, 1994). If imaging is uncertain, then simple two-view radiography of the abdomen is useful to define head inclination. The sonographic accuracy of fetal weight estimation does not appear limited by breech presentation (McNamara, 2012). Although variable, many protocols use fetal weights < 2500 g and > 3800 to 4000 g or evidence of growth restriction as exclusion criteria for planned vaginal delivery (Azria, 2012; Kotaska, 2009). Similarly, a biparietal diameter (BPD) > 90 to 100 mm is often considered exclusionary (Giuliani, 2002; Roman, 2008).

Pelvimetry

This assessment of the bony pelvis before vaginal delivery may be completed with one-view computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, or plain film radiographs. Although there are no comparative data among these modalities for pelvimetry, computed tomography is favored due to its accuracy, low radiation dose, and widespread availability (Thomas, 1998). At Parkland Hospital, we use CT pelvimetry when possible to assess the critical dimensions of the pelvis (Chap. 2, p. 32). Although variable, some suggest specific measurements to permit a planned vaginal delivery: inlet anteroposterior diameter ≥ 105 mm; inlet transverse diameter ≥ 120 mm; and midpelvic interspinous diameter ≥ 100 mm (Azria, 2012; Vendittelli, 2006). Others use maternal-fetal biometry correlation. Appropriate values include: the sum of the inlet obstetrical conjugate minus the fetal BPD is ≥ 15 mm; the inlet transverse diameter minus the BPD is ≥ 25 mm; and the midpelvis interspinous diameter minus the BPD is ≥ 0 mm (Michel, 2011).

Decision-Making Summary

Decision-Making Summary

As outlined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b), risks versus benefits are weighed and discussed with the patient. If possible, this is preferably done before admission. A diligent search is made for any other complications, actual or anticipated, that might warrant cesarean delivery. Common circumstances are listed in Table 28-1. For a favorable outcome with any breech delivery, at the very minimum, the birth canal must be sufficiently large to allow passage of the fetus without trauma. The cervix must be fully dilated, and if not, then a cesarean delivery nearly always is the more appropriate method of delivery if suspected fetal compromise develops.

TABLE 28-1. Factors Favoring Cesarean Delivery of the Breech Fetus

Lack of operator experience

Patient request for cesarean delivery

Large fetus: > 3800 to 4000 g

Apparently healthy and viable preterm fetus either with active labor or with indicated delivery

Severe fetal-growth restriction

Fetal anomaly incompatible with vaginal delivery

Prior perinatal death or neonatal birth trauma

Incomplete or footling breech presentation

Hyperextended head

Pelvic contraction or unfavorable pelvic shape determined clinically or with pelvimetry

Prior cesarean delivery

MANAGEMENT OF LABOR AND DELIVERY

Methods of Vaginal Delivery

Methods of Vaginal Delivery

There are important fundamental differences between labor and delivery in cephalic and breech presentations. With a cephalic presentation, once the head is delivered, the rest of the body typically follows without difficulty. With a breech, however, successively larger and less compressible parts are born. Spontaneous complete expulsion of the fetus that presents as a breech, as subsequently described, is seldom accomplished successfully. Therefore, as a rule, vaginal delivery requires skilled participation for a favorable outcome.

There are three general methods of breech delivery through the vagina:

1. Spontaneous breech delivery. The fetus is expelled entirely spontaneously without any traction or manipulation other than support of the newborn.

2. Partial breech extraction. The fetus is delivered spontaneously as far as the umbilicus, but the remainder of the body is extracted or delivered with operator traction and assisted maneuvers, with or without maternal expulsive efforts.

3. Total breech extraction. The entire body of the fetus is extracted by the obstetrician.

Labor Induction and Augmentation

Labor Induction and Augmentation

Induction or augmentation of labor in women with a breech presentation is controversial, and data are limited. Marzouk and associates (2011) found similar perinatal neonatal outcomes with spontaneous labor or with cervical preparation and induced labor. In many studies, improved rates of successful vaginal delivery and neonatal outcome are associated with orderly labor progression. Thus, some protocols avoid augmentation, whereas others recommend it only for hypotonic contractions (Alarab, 2004; Kotaska, 2009). In women with a viable fetus, at Parkland Hospital, we attempt amniotomy induction but prefer cesarean delivery instead of oxytocin induction or augmentation.

Management of Labor

Management of Labor

On arrival, rapid assessment should be made to establish the status of the membranes, labor, and fetal condition. Surveillance of fetal heart rate and uterine contractions begins at admission, and immediate recruitment of necessary staff should include: (1) an obstetrician skilled in the art of breech extraction, (2) an associate to assist with the delivery, (3) anesthesia personnel who can ensure adequate analgesia or anesthesia when needed, and (4) an individual trained in newborn resuscitation.

For the mother, an intravenous catheter is inserted, and crystalloid infusion begun. Emergency induction of anesthesia or maternal resuscitation following hemorrhage from lacerations or from uterine atony are but two of many reasons that may require immediate intravenous access.

Assessment of cervical dilatation and effacement and the station of the presenting part is essential for planning the route of delivery. If labor is too far advanced, there may not be sufficient time to obtain pelvimetry. This alone, however, should not force the decision for cesarean delivery. Commonly, satisfactory progress in labor is the best indicator of pelvic adequacy (Biswas, 1993; Nwosu, 1993). Sonographic fetal biometry and assessment of head flexion are completed. And if not performed as part of earlier prenatal care, fetal anatomy is evaluated. Ultimately, the choice of abdominal or vaginal delivery is based on factors discussed earlier and listed in Table 28-1.

For managing labor and delivery of a breech fetus, additional help is required. One-on-one nursing is ideal during labor because of the risk of cord prolapse or occlusion, and physicians must be readily available for such emergencies. Guidelines for monitoring the high-risk fetus are applied as discussed in Chapter 24 (p. 497). During the first stage of labor, the fetal heart rate is recorded at least every 15 minutes. Most clinicians prefer continuous electronic monitoring. If a nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern develops, then a decision must be made regarding the necessity of cesarean delivery.

When membranes are ruptured, either spontaneously or artificially, the cord prolapse risk is appreciable and is increased when the fetus is small or when the breech is not frank (Dilbaz, 2006; Erdemoglu, 2010). Therefore, a vaginal examination should be performed following rupture to exclude prolapse, and special attention should be directed to the fetal heart rate for the first 5 to 10 minutes following membrane rupture.

Cardinal Movements with Breech Delivery

Cardinal Movements with Breech Delivery

Engagement and descent of the breech usually take place with the bitrochanteric diameter in one of the oblique pelvic diameters. The anterior hip usually descends more rapidly than the posterior hip, and when the resistance of the pelvic floor is met, internal rotation of 45 degrees usually follows, bringing the anterior hip toward the pubic arch and allowing the bitrochanteric diameter to occupy the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. If the posterior extremity is prolapsed, however, it, rather than the anterior hip, rotates to the symphysis pubis.

After rotation, descent continues until the perineum is distended by the advancing breech, and the anterior hip appears at the vulva. By lateral flexion of the fetal body, the posterior hip then is forced over the perineum, which retracts over the fetal buttocks, thus allowing the infant to straighten out when the anterior hip is born. The legs and feet follow the breech and may be born spontaneously or require aid.

After the birth of the breech, there is slight external rotation, with the back turning anteriorly as the shoulders are brought into relation with one of the oblique diameters of the pelvis. The shoulders then descend rapidly and undergo internal rotation, with the bisacromial diameter occupying the anteroposterior plane. Immediately following the shoulders, the head, which is normally sharply flexed on the thorax, enters the pelvis in one of the oblique diameters and then rotates in such a manner as to bring the posterior portion of the neck under the symphysis pubis. The head is then born in flexion.

The breech may engage in the transverse diameter of the pelvis, with the sacrum directed anteriorly or posteriorly. The mechanism of labor in the transverse position differs only in that internal rotation is through an arc of 90 rather than 45 degrees. Infrequently, rotation occurs in such a manner that the back of the fetus is directed posteriorly instead of anteriorly. Such rotation should be prevented if possible. Although the head may be delivered by allowing the chin and face to pass beneath the symphysis, the slightest traction on the body may cause extension of the head, which increases the diameter of the head that must pass through the pelvis.

Partial Breech Extraction

Partial Breech Extraction

With all breech deliveries, unless there is considerable relaxation of the perineum, an episiotomy should be made and is an important adjunct to delivery. Ideally, the breech is allowed to deliver spontaneously to the umbilicus. Delivery is easier, and in turn, morbidity and mortality rates are, at least intuitively, lower. Delivery of the breech draws the umbilicus and attached cord into the pelvis, which stretches and compresses the cord. Therefore, once the breech has passed beyond the vaginal introitus, the abdomen, thorax, arms, and head must be delivered promptly either spontaneously or assisted, as described here.

The posterior hip will deliver, usually from the 6 o’clock position, and often with sufficient pressure to evoke passage of thick meconium (Fig. 28-5). The anterior hip then delivers, followed by external rotation to a sacrum anterior position. The mother should be encouraged to continue to push. As the fetus continues to descend, the legs are sequentially delivered by splinting the medial aspect of each femur with the operator’s fingers positioned parallel to each femur, and by exerting pressure laterally to sweep each leg away from the midline.

FIGURE 28-5 The hips of the frank breech are delivering over the perineum. The anterior hip usually is delivered first.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree