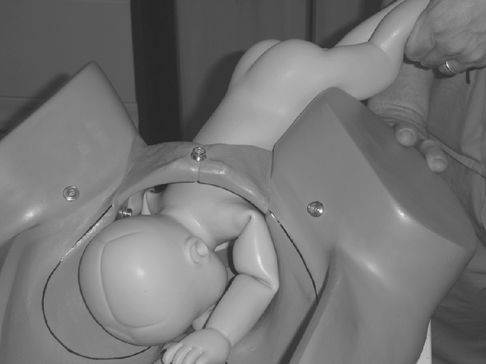

Displacement of the fetal breech at ECV using the ‘one pole’ method.

Flexing the fetal head after displacement of the breech.

Vaginal Breech Birth

Selection for Vaginal Breech Birth

Practitioners need to be aware when considering vaginal breech birth that published studies usually work within guidance and exclusions. The Term Breech Trial had clear guidance for conduct of the vaginal birth arm of the trial [1] that was agreed by a consensus group. Other published studies have other exclusions [5] and have argued that selection and guidance for conduct can influence outcomes (see Table 11.3).

| Other indication for caesarean birth | |

| Footling breech or kneeling (feet below the buttocks) breech presentation | |

| Known hyperextension of neck (ultrasound or clinical impression) | |

| Large fetus (more than 4 kg) | |

| Suspected fetal growth restriction | |

| Previous caesarean section | |

| Clinically inadequate pelvis | |

| Lack of availability of experienced obstetrician | |

| Insufficient throughput to maintain safety |

Success is more likely if both the mother’s pelvis and the baby are of average proportions, and the Term Breech Trial excluded fetuses known to be over 4 kg, as do other groups [5]. The presentation should be either frank (hips flexed, knees extended) or complete (hips flexed, knees flexed but feet not below the fetal buttocks). Where presentation was not so, the risk of cord prolapse was 5.6% [11].

Hyperextension of the fetal head increases the risk of nuchal arms and head entrapment. Assessment of pelvic size is rarely carried out in modern practice, but should be considered if contemplating vaginal breech birth; there appears no advantage to formal pelvimetry.

Neither presentation for the first time in labour nor previous caesarean birth are absolute contraindications to vaginal breech birth, although the French groups have this as part of their consensus guideline.

There has been much debate about facilities and personnel. Subanalysis of the Term Breech Trial showed the absence of an experienced practitioner (variously defined) increased the risk of poor outcomes [11]. Analysis of the French multi-centre study showed that a senior obstetrician was present at 95% of births [6].

The birth setting is more contentious. There are midwifery practitioners who conduct vaginal breech births and a number of case reports and individual stories, but no published series that allow a systematic assessment of either safety or success. At present any recommendation to women would need to be giving birth in a hospital setting. As contentious is whether size and throughput should matter. There is some evidence that adverse neonatal outcome at caesarean birth for breech is higher (three-fold) in units with fewer than 1000 births in a US setting. The PREMODA group analysed factors that were associated with adverse outcomes and one was birth in a unit delivering fewer than 1500 women [21]. Logically, teams working in smaller centres will have less exposure to vaginal breech birth, and need to consider whether they can safely support such requests. The RCOG [11] recommended consideration of referral in some circumstances.

Conduct of Labour

The 7th Report of the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirth and Deaths in Infancy [22] highlighted the need for senior involvement in supervising labour in intended or unexpected breech births. The Term Breech Trial and others have confirmed the importance of such involvement early.

Although there are few data to guide labour conduct in breech presentation, few experienced practitioners believe that labour progress should be allowed to be the same as for cephalic presentation. Groups who have demonstrated comparable outcomes with planned CS and who achieve higher vaginal breech birth rates rarely regard a rate of progression of the first stage of less than 0.5 cm/h as normal [5,7] and these data provide strong evidence for intrapartum guidance to differ [14]. The mean length of the active second stage in these studies is an hour, and given the good outcomes reported advice on shortening the duration of active pushing before resorting to CS may be wise.

There is no robust evidence that epidural analgesia is an advantage for breech birth. Similarly, the evidence supporting the use of continuous electronic FHR monitoring is no more robust for breech presentation than it is for general use, but most authorities advise its use. The CESDI report [22] was critical of the management of fetal monitoring. Again, groups with good vaginal breech rates and safety advocate continuous electronic FHR monitoring as part of their guidance. The data on fetal blood sampling from the buttock are too few to justify its use outside a research setting.

Induction of labour can be considered for a planned breech birth, as the evidence against is not substantial, but augmentation in current practice should be avoided unless there is careful review of uterine activity and labour progress at consultant/specialist level. Subgroup analysis of the Term Breech Trial suggested poorer outcomes if augmentation occurred [11], confirming the advice of the CESDI report [22] (see Table 11.4).

| Admission assessment (most senior staff available) | |

| Fetal size, pelvic size, breech type, attitude fetal head | |

| If ultrasound equipment or the skills to assess the above are not available, recommend caesarean section Inform consultant/specialist staff of admission | |

| Advise continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring | |

| Discuss analgesia requirements; consider epidural analgesia | |

| Careful review of first stage progress Careful review of descent as well as cervical progress Oxytocin augmentation only after senior review and where clinically poor uterine activity (not simply for failure of cervical dilatation) | |

| Where electronic fetal heart rate monitoring changes, senior review; fetal blood sampling not indicated |

Conduct of Breech Birth

There are no compelling data comparing safety or efficacy of the various techniques utilized in breech birth. Therefore debates on whether classical techniques are superior to Bracht manoeuvres, or whether forceps are superior to Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet techniques are simply personal opinions. Comparison of Bracht techniques versus classical techniques in 1953 recommended the Bracht technique. A study in 1991 showed some subtle neurodevelopmental differences in neonatal outcomes comparing classical and Bracht techniques. In the most recent study [23], Bracht and similar manoeuvres appeared associated with less neonatal morbidity. The techniques used by midwifery practitioners are essentially derived from Bracht.

The Mauriceau technique was compared with other techniques by one French group and showed no differences in neonatal outcomes. Older studies suggested improved neonatal outcomes where forceps were used for the after-coming head. Manoeuvres for difficulty with the arms, such as the classical method described by Kunzel and Kirschbaum [24], the method of Muller [25] or Lovset’s manoeuvre [26], have rarely been compared.

Therefore there are only four general rules for birth of the breech:

1. learn and become comfortable with one set of techniques;

2. keep your hands to yourself until the umbilicus is delivered;

3. use rotation, not traction, if in trouble; and

4. make sure an experienced practitioner is present, as well as anaesthetic and paediatric help.

Assisted Breech Delivery

Current advice is to use the dorsal lithotomy position until such time as convincing evidence appears for alternatives. One recent study audited outcomes for a small cohort of births using the all-fours position compared with the classical position [26]. Although perineal trauma was reduced and there were no serious neonatal complications, cord artery pH was significantly lower in the all-fours group (see Table 11.5).

| Place in lithotomy when breech distending perineum | |

| Consider episiotomy | |

| Hands off the baby until the umbilicus appears (unless sacro-posterior) | |

| Avoid handling the umbilical cord unless clearly under tension | |

| If extended legs and do not deliver, flex the leg outwards using two or three fingers; no traction is needed | |

| Allow spontaneous birth of the arms, then support the body if necessary | |

| Encourage an assistant to carry out suprapubic pressure on the head to keep it flexed | |

| If arms do not deliver and are flexed, then you can use pelvic grip (Figure 11.3) to rotate baby to bring the elbow into view and sweep the arms out | |

| Once arms are delivered, support the baby; do not let it ‘hang’ | |

| Use forceps or Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet manoeuvre to deliver the head (Figures 11.4–11.6) |

Pelvic grip for manipulation at vaginal breech birth.

Forceps to the after-coming head.

Upper hand position at Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet procedure.

Lower hand position at Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet manoeuvre.

Much of assisted breech birth is common sense and allowing normal birth to occur. Although episiotomy may not always be strictly necessary, particularly in a parous woman, it is advised in case more complex manoeuvres become necessary.

The manoeuvres to deliver the normal positions of the arms and legs require simple flexion and it should not be necessary to pull on the trunk to gain access.

There is debate on whether the baby should ‘hang’ near-vertically, as traditional teaching has it. Unsupported ‘hanging’ can result in uncontrolled birth of the head, and increases extension of the neck. It is best to support at an angle, resting the baby on the forearm.

Before attempting any of the manoeuvres to deliver the head, allow some time for the nape of the neck to become visible. Where using forceps, an assistant will be needed to support the body and keep the arms out of the way. Wrigley’s forceps are adequate for this task, unless Piper’s forceps are available; these were designed for this task, having a longer shank (Figure 11.4).

The Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet manoeuvre requires draping of the baby over the forearm with the legs on either side. The classic description by Smellie, and before him, Gifford [25], involved placing a finger in the mouth, but current advice is that this is not necessary. The manoeuvre involves placing the index and middle fingers of one hand on either side of the fetal maxilla to allow some flexion, and the other hand is placed on the back with the middle finger up the occiput. Birth is by flexion (Figures 11.5 and 11.6).

Bracht Technique

This technique has been utilized for many years in mainland Europe [24]. It follows and exaggerates the planes of a spontaneous breech birth. The French studies showing better outcomes predominately use this technique. The key is the particular grasp of the baby, keeping the thighs flexed against the abdomen and then rotating the baby, using gentle pressure around the maternal symphysis (see Table 11.6 and Figure 11.7).

Bracht technique

| Place in lithotomy when breech distending perineum | |

| Consider episiotomy | |

| Hands off the baby until the umbilicus appears (unless sacro-posterior) | |

| Avoid handling the umbilical cord unless clearly under tension | |

| Abdominal then suprapubic pressure to maintain head flexion | |

| Grasp the baby with the thumbs pressing the baby’s thigh against its stomach and the rest of the hands over the sacral and loin area (pelvic grip) | |

| While the woman is pushing, gently rotate or lift the baby around the maternal symphysis, maintaining upwards movement but without traction (Figure 11.7). | |

| Spontaneous birth of the legs and arms. | |

| Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet or forceps for the head |

Initial rotation during Bracht technique.

Manoeuvres for Delay in Delivery of the Arms

This can present as either extended arms or where one or both arms are flexed behind the head. Careful observation of the shoulder blade should forewarn.

Lovset’s Manoeuvre

This manoeuvre was described in 1937. It involves using the fact that the posterior shoulder will be lower in the pelvis. Using the pelvic grip, the baby is rotated to an oblique position and gentle traction applied. The baby is then lifted in that plane to further encourage descent of the posterior shoulder and arm (Figure 11.8). The baby is then rotated through 180°, presenting the arm under the symphysis, where it can be hooked out. The baby is then rotated through 180° again to present the other shoulder and arm.

Lovset’s manoeuvre showing entry of posterior shoulder into pelvis.

Classical Arm Development

This uses similar principles to Lovset’s approach by making the posterior shoulder available. The baby is grasped by the feet and swung outwards and upwards in an oblique plane away from the shoulder of interest (Figure 11.9). The other hand is then inserted into the posterior vagina and along the arm. When sufficiently confident the arm is then swept across the chest and out. To deliver the other arm the baby is held along its sides and rotated through 180° to bring the other shoulder into the posterior vagina. The ‘swinging’ manoeuvre is repeated to effect delivery of the other arm.

Classical arm manoeuvre showing entry of posterior shoulder into pelvis.

An alternative method has been suggested in which the anterior arm is delivered first by swinging the baby in the opposite direction.

Nuchal Arms

This should not happen and is usually a consequence of inappropriate traction. Where only one arm is involved, Lovset’s manoeuvre should be enough to free the arm.

An alternative method is simply to rotate, using the pelvic grip, in the direction the arm is pointing. This will usually bring the elbow under the symphysis.

When both arms are involved, management is difficult and one may have to try both rotations to see which is the most likely arm to be deliverable. Even in very skilled hands trauma is common.

Alternatively the classical technique described before can be successful for this. Rotate (swing) the fetus towards the hand of the posterior nuchal arm and above the level of the maternal symphysis. This may result in delivery of the posterior arm, but if not it allows room for the occiput to slip below the elbow. A hand can be placed over the shoulder and behind the humerus to allow pressure on the humerus with delivery in front of the face.

If these manoeuvres fail, it is legitimate, in the author’s opinion, to force the arm across the face to deliver. Humeral or clavicular fractures are very likely, but will not cause long-term harm; perinatal hypoxia does.

Head Entrapment

Other than advice on incising the cervix at 4 and 7 o’clock where entrapment is secondary to incomplete dilatation, there is little in the literature to guide clinicians on this rare but feared complication.

William Smellie’s original description of the manoeuvre that bears his name was for its use for a head trapped high in the pelvis.

Symphysiotomy is the classic technique that is suggested, although its morbidity in unskilled hands is formidable. More recently, case reports using McRoberts’ position have appeared, and there is logic in consideration of this position, where obstruction is above the symphysis. Smellie’s manoeuvre or forceps should be able to deliver where the head is trapped in the mid-pelvis (see Table 11.7).

| Call for anaesthetic support; prepare for caesarean birth | |

| Check cervix is fully dilated; if not, consider incision of cervix (4 and 7 o’clock) | |

| Try combination of Mauriceau–Smellie–Viet and suprapubic pressure | |

| Repeat with McRoberts’ position | |

| Mid-cavity forceps | |

| Rotate and lift the body into a lateral position, apply suprapubic pressure to flex the head into the pelvis, then rotate back and continue with previous techniques | |

| Symphysiotomy if adequate training | |

| Caesarean section; use ventouse to aid extraction if necessary |

Multiple Birth

Multiple Birth at Term

There has been a steady increase in the proportion of multiple pregnancies delivered by elective caesarean birth. The most marked impetus came from Keily’s review [27] of over 16 000 multiple births in New York, where he demonstrated increased overall neonatal mortality rates for infants weighing between 2501 g and 3000 g and over 3001 g, and demonstrated intrapartum mortality rates that, although low (1.22 per 1000), were 3.5 times those of similar birth weight singleton infants. There remained debate over mode of birth, and particularly whether guidance could be tailored to presentation, birth weight or gestation.

In contrast, a systematic review carried out by the group planning the Twin Birth Study did not demonstrate differences in mortality in the literature from 1980 to 2001. This group showed an increased rate of low five minute Apgar scores, but increased overall neonatal morbidity associated with CS [28].

A series of papers using UK national data from Smith and colleagues consistently demonstrated increased risk for the second twin, culminating in a large study of twins in England, Wales and Northern Ireland using the perinatal death reporting system [29]. There were no differences linked to mode of birth for births less than 36 weeks’ gestation, but a relative risk of perinatal death secondary to anoxia of 3.4 for second twins where birth was planned vaginally. The absolute risk to the second twin was 3.2 per 1000 compared with planned caesarean birth. He consistently identified twin birth weight discrepancy as the variable associated with the highest risk.

US data were conflicting. The analyses by Wen and colleagues [30] in term pregnancies showed an increased risk of overall mortality and asphyxial mortality only in those infants born by CS after vaginal birth of the first twin, with low rates overall (1 per 10 000 for caesarean birth and 2.4 per 1000 for vaginal then caesarean birth). There were no differences where both delivered vaginally. The rate of second twin CS was 9.45%. In contrast, the massive study by Sheay et al. [31] of over 290 000 twin pregnancies from national data sets showed no difference in neonatal mortality between twins 1 and 2, even when broken down into birth weight groups. Looking at their data by mode of birth, there was a significant increase in neonatal deaths at vaginal birth, but odds ratios were only 1.08. These data were not controlled for gestation or birth weight. Examination of cause of death (through ICD coding) showed no differences in deaths coded as intrauterine hypoxia or birth asphyxia. Nova Scotian data, from a well-validated data set, followed [32], although looking at composite outcomes. This data set showed a three-fold increase in composite perinatal morbidity for the second twin in planned vaginal births, with no differences in outcomes by birth order when planned caesarean birth. The relative presentation of twins did not seem to influence outcomes, but once again inter-twin size difference did. The odds of poor outcome were 3.75 times greater where twin 2 was more than 20% larger than twin 1.

More recent non-randomized data that have examined planned mode of birth rather than actual mode have shown no substantial clinical differences in outcomes by planned mode of birth [33,34]. The WHO study [35] of twins in low- and middle-income countries did not find differences in maternal or neonatal morbidity by presentation of the second twin. This was reassuring data, given the overall higher rates of morbidity and the more variable access to skills and facilities. Systematic review of planned birth data [36] shows no difference in maternal or neonatal outcomes. This review was also unable to demonstrate any difference when analysis was performed on actual birth mode.

To some extent the debate was on hold until the Twin Birth Study was reported [37]. This was a large multinational trial of planned vaginal birth versus planned CS for twin pregnancies between 32 and 37 + 6 weeks’ gestation. It involved 2800 twin pairs where the first twin was a cephalic presentation. Ultimately 90.7% of the planned CS group had CS and 39.6% of the planned vaginal birth group had CS for both twins. No differences in composite neonatal morbidity or maternal outcomes were seen and there was no difference in neonatal mortality.

Although, like the Term Breech Study, this trial is unlikely to be the last word on the topic, its findings combined with recent analyses of planned mode of birth provide strong evidence that planned CS for uncomplicated twin pregnancies should not be recommended practice. Where there are no other contraindications to vaginal birth, vaginal birth should be the default position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree