11 Breast problems

Breast Symptoms Presenting to GPs

Nearly all women today know of someone, either a friend or relative, who has had breast cancer. This has led to enormous anxiety among women and a greater preparedness to present to doctors with their concerns about changes they notice in their breasts. There is strong evidence that most women first discover breast lumps or other abnormalities themselves1 and that most patients with breast symptoms are seen first by their GP.2 On average, a GP would see between 133 and 34 women with new breast problems in 1 year and, of these, one would have cancer.1

A recent Dutch study characterising breast symptoms occurring in primary care found that breast symptoms were reported in about 3% of all visits by female patients and that breast pain and breast mass were the most common breast-related complaints. Breast symptom complaints were highest among women aged 25 to 44 years (48 per 1000) and among women aged 65 years and older (33 per 1000). Of the women complaining of breast symptoms, only 3.2% had breast cancer diagnosed. A breast mass had a markedly elevated positive likelihood ratio for breast cancer (15.04; 95% confidence interval, 11.74–19.28).4

Breast Lumps

Is it normal breast tissue or something I should be concerned about?

What is it most likely to be?

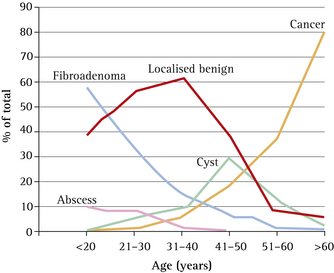

When GPs see women of all different ages presenting with the same symptom (a breast lump) it is essential to remember the changing frequencies of different discrete breast lumps with age (Fig 11.1). Women in their 20s and 30s are much more likely to have a fibroadenoma. Breast

FIGURE 11.1 Changing frequencies of different discrete breast lumps with age

(From Dixon & Mansel,35 with permission from Anthea Carter)

Conversely, it is worthwhile remembering the differing frequencies of presenting symptoms of breast cancer (Table 11.1).

TABLE 11.1 Relative frequencies of presenting symptoms of breast cancer*

| Symptom | Frequency of presentation |

|---|---|

| Lump | 76% |

| Pain alone | 10% |

| Nipple changes | 8% |

| Breast asymmetry or skin dimpling | 4% |

| Nipple discharge | 2% |

* Based on the Presentation of Symptomatic Women to the Breast Unit of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, in 2004.

(From NBOCC5)

How should a rigorous clinical breast examination be carried out?

What are the critical issues in the evaluation of a woman with a breast lump?

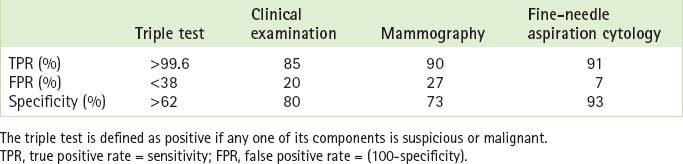

If a lump is found, the next question is to determine the likelihood of cancer. This can be assessed using the triple test (clinical breast examination, mammography and fine-needle aspiration cytology); a positive triple test is found in 99.6% of breast cancers. Negative results in all components of the triple test provide good evidence that a cancer is unlikely (<1%).5 The accuracy of the triple test and each of its components is given in Table 11.2 (p 186).

The problem with the triple test, however, is the varying degree of sensitivity and specificity of the different components of the test. For example, a clinical breast examination may be more sensitive in the hands of an experienced practitioner. Mammography is less effective in younger women,6 in whom ultrasound has a lower false positive rate and is more sensitive.

When do breast cysts occur?

While breast cysts can occur at any age, they are more common in those over 40, accounting for <10% of breast masses in those under 40.6

What should a GP do when confronted with an obvious breast cyst?

If an ultrasound or mammogram reveals a simple cyst, the next step is to aspirate the cyst using a fine-bore needle (Fig 11.2). Routine cytologic examination of cyst fluid is not indicated if it appears normal (straw to dark-green colour) and no lump remains,5 because of the low likelihood of cancer and the fact that cytologic identification of atypical cells in cyst fluid is not uncommon. This results in the clinical dilemma of a patient whose cyst resolves with aspiration and whose mammogram is normal, but whose cytology report indicates the need for biopsy.7

Women should be advised to return for review if the cyst refills; if there is persistent refilling, the patient should be referred to a surgeon.5 One follow-up study of 389 women who underwent cyst aspiration found that 44 women had a recurrent cyst and 20 had a solid mass at the aspiration site. In biopsies of the 20 solid masses, two cancers were found.8 If there is bloody fluid or a lump remains after aspiration of what appears to be a simple cyst on imaging, the fluid should be sent for cytological testing and the patient referred to a surgeon.

What if non-palpable cysts are found on mammography?

If they are confirmed as simple cysts on ultrasound examination, they require no treatment.

What are fibroadenomas?

Fibroadenomas used to be considered benign tumours of the breast. They are now considered to be aberrations of normal breast development, histologically resembling a hyperplastic breast lobule.9 They are also known as the ‘breast mouse’, because they appear to be very mobile.

Fibroadenomas are relatively common, accounting for 12% of all palpable breast masses,10 60% of which are in women <20 years.11

Is there a relationship between fibroadenomas and breast cancer?

The general consensus is that having a fibroadenoma does not bring about an increased risk of breast cancer.10,12

What do fibroadenomas feel like?

While fibroadenomas are often very characteristic, the diagnosis is correct only in half to two-thirds of cases.13,14 Therefore, a clinical diagnosis is not sufficient to exclude cancer, even in young women, and all women with discrete masses should have a triple test.

How are fibroadenomas managed?

If cancer is excluded using the triple test, the patient has a choice between conservative management or surgical excision. If conservative management is chosen, the limitations of the triple test should be explained to the patient (approximately 1% of cancers can be misdiagnosed), the patient should be followed up on a regular basis, with repeat ultrasonography every 6–12 months, and be reassessed if there is any change.9

When should I refer the patient to a surgeon?

Indications for referral are described in Box 11.1. Referrals should be directed towards surgeons with expertise in breast disease.5

BOX 11.1 Indications for surgical referral in the presence of a breast change

The patient should be referred to a surgeon: