Physical Examination

As part of the initial history in a premenopausal woman, a thorough evaluation of the menstrual history including regularity, pain with cycles, and the date of the last menstrual cycle is essential prior to starting the breast examination. The breast examination is best done 7 to 9 days after the menstrual cycle has started because this is at the nadir of hormonal stimulation. The timing of the exam is not important in menopausal women or women taking hormonal treatments that cause ovarian suppression, for example, oral contraceptives.

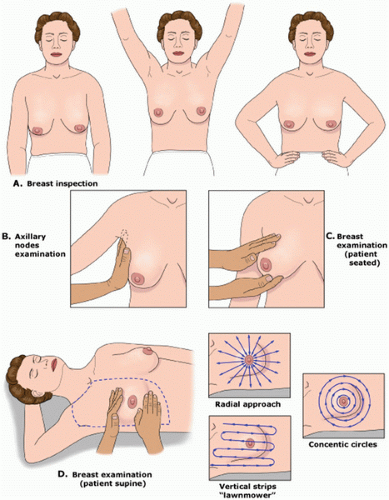

The technique of breast examination should include inspection and palpation of the entire breast and lymph node basins (

Fig. 16.1). Breasts should be inspected initially with the patient sitting in an upright position with hands relaxed by her sides. Both breasts should be compared for size, symmetry, contour, and any skin changes. Many women have a small size discrepancy between both breasts. However, any recent change in the size of the breast should be further evaluated. Previous surgical biopsies can change the contour of the breast and should be noted on examination. Edema or peau d’orange which occurs as a result of obstruction of the

dermal lymphatics by tumor can be easily visualized. In addition, local erythema of the breast which can be caused by cellulitis, mastitis, or an abscess can be differentiated from inflammatory breast cancer, which usually presents as diffuse erythema and edema of the breast. However, diagnosis will require biopsy for inflammatory breast cancer.

The nipple areola complex should be examined for changes in the skin, symmetry, and retraction. Newonset nipple retraction should be considered suspicious for malignancy. Ulceration or eczematoid lesions of the nipple areola complex can be a sign of Paget disease.

The patient should raise her arms over her head and then place her hands against her hips, resulting in contraction of the pectoralis muscles, which can demonstrate subtle nipple retraction and dimpling of the breast skin. With the patient still in the upright position, the regional lymph node basins, including cervical, supraclavicular, and axillary lymph nodes should be examined. Palpable lymph nodes should be characterized by their size, whether they are firm, mobile or fixed, or tender to palpation. Each breast should then be palpated by placing one hand under the breast supporting it, while using the flat portion of the other hand to examine the entire breast.

The patient is then placed in the supine position, and the ipsilateral arm is raised above the head. For patients with large pendulous breasts, a towel or pillow can be placed beneath the ipsilateral shoulder to elevate the breast that is being examined. The breast should be examined either in a concentric circle or in a radial pattern, and palpation should extend from the clavicle superiorly, laterally to the latissimus dorsi muscle (posterior axillary line), inferiorly to the costal margin, and medially to the sternum. This is performed with one hand placed on the breast to stabilize the breast, while the flat surface of the other hand is used to examine the breast. Palpation of the breast should include temperature differences of the surface of the skin, edema, focal or generalized tenderness, the presence of a dominant mass, and nipple discharge. Diffuse nodularity predominantly in the upper outer quadrants of the breast is a normal finding especially in premenopausal women. Comparing physical findings of both breasts is helpful in further differentiating nodularity or other areas of palpable concern. If there is an area of nodular breast tissue in a premenopausal woman that is nonspecific, the patient may be asked to return at a different time in her menstrual cycle for a physical examination. A dominant breast mass should be different from the surrounding breast tissue on examination. If a breast mass is noted, the size (in centimeters), location, and characteristics including tenderness, mobility, and firmness should be documented. It is helpful to record the location of any abnormality on the breast by documenting its position and the distance in centimeters from the areola because this will help on subsequent follow-up examinations by either the initial physician or other examiners. Diagrammatic depictions are quite useful, and many electronic medical records do have mechanisms for the creation of such figures. In addition, if a patient reports a palpable mass that is not found on physical examination, it is important to have the patient indicate the area of the palpable abnormality noted on breast self-examination. Physical examination alone will not distinguish between benign and cancerous lesions so any abnormal findings on examination should be further evaluated using imaging, for example, ultrasound or mammography, and if necessary, biopsy.