Breast Disease During Pregnancy and Lactation

The breasts normally undergo remarkable physiologic changes during pregnancy and lactation. Numerous diseases, ranging from physiologic and/or anatomic abnormalities to neoplasms, may affect the breasts. Some abnormal conditions are unique to pregnancy and lactation. Finally, as a result of normal physiologic changes during pregnancy, some diseases, particularly malignant neoplasms, may be more difficult to diagnose.

NORMAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

NONPREGNANT

The breast is a modified sweat gland underlying subcutaneous tissue and skin. The main functional unit consists of a single gland composed of two major parts, the terminal duct-lobular unit and a large duct system (Fig. 33-1). The terminal duct-lobular unit is formed by a lobule and terminal ductule. This connects with the large duct system, which is a series of increasingly larger ducts leading from the terminal ducts to a collecting duct, which empties into the nipple. Division of breast tissue into these two components also reflects disease processes that affect the breast. Conditions such as fibrocystic changes, ductal hyperplasias, and carcinomas affect the terminal duct-lobular unit, whereas the large duct system is the site of duct ectasias and papillomas (Appozardi, 1979; Wellings and associates, 1975).

FIGURE 33-1. Illustration of the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU) of the breast.

The lobules and ducts consist primarily of a two-cell type epithelium. The luminal epithelium consists mainly of secretory and absorptive cells; for histopathologic and function purposes, these cells may be considered as a single entity. Underlying the luminal epithelium is a network of myoepithelial cells, which function as contractile elements that assist in the secretory process.

Functional breast changes are largely under hormonal control and may therefore demonstrate a variety of macro-and microscopic changes under normal conditions. The pre-pubertal breast is largely inactive, containing small lobules and infrequent ducts. Hormonal changes during puberty result in growth and differentiation. Although estrogen provides the major influence, full differentiation of breast tissue requires an interplay of a variety of hormones, including prolactin, progesterone, insulin, cortisol, thyroxine, growth hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (Fig. 33-2A; Topper, 1970; Meduri and colleagues, 1997).

FIGURE 33-2. A. Normal functional breast tissue. The breast is affected by hormonal influence. Estrogen primarily stimulates ductal epithelial proliferation; progesterone stimulates growth of the lobule. For clinical and histopathologic purposes, distinguishing between the proliferative and secretory phases is usually unnecessary. B. Postmenopausal atrophy. With the lack of hormonal stimulation, atrophic ducts are the main component present.

During the reproductive years, the breast exhibits changes that vary according to the menstrual cycle. In simple terms, estrogen primarily stimulates epithelial proliferation in the ductal portion of the glands, and progesterone influences growth of the lobule (Speroff and associates, 1989). Hormonal manipulation during reproductive years affects the breast as it affects other hormonally dependent female organs.

The breast may undergo involution during postmenopausal years, although this is dependent on exogenous administration or endogenous conversion of sex hormones. Both the epithelium and stroma become inactive; the epithelium atrophies and the stroma may be replaced by dense fibrous connective tissue (Fig. 33-2B). Histologic preparations usually demonstrate minimal lobular tissue. The lobules may undergo microcystic change; however, these are not fibrocystic changes because of lack of proliferation.

PREGNANCY AND LACTATIONAL CHANGES

The breasts undergo marked physiologic and microanatomic changes during pregnancy and lactation. The physiology of lactation requires a complex interplay of hormones already described as being involved in differentiation of the breast, at, however, significantly altered levels. Additionally, there is the contribution of oxytocin, and to some extent, human placental lactogen.

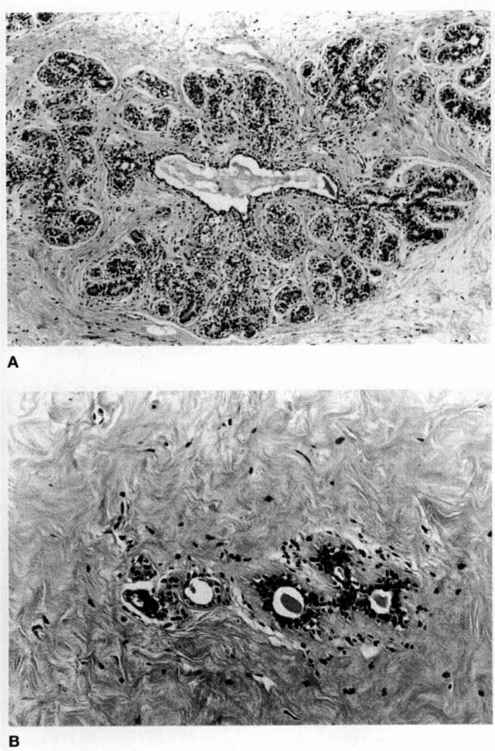

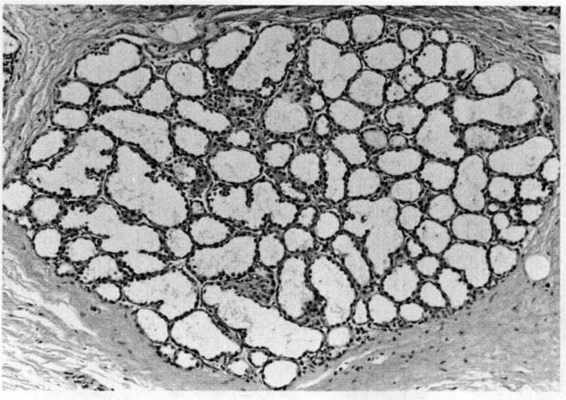

During pregnancy, numerous secretory glands develop from gland buds and there is proliferation of all cell types (Joshi and colleagues, 1986). In contrast to nonpregnancy, in which stroma predominates over glands, the breast during pregnancy is characterized by many more glands and by progressively decreasing stroma (Cotran and associates, 1989). The epithelial cells develop secretory vacuoles, which contain lipid, becoming most predominant in the third trimester. Some apocrine secretion is apparent as the vacuoles develop; however, significant secretions are not present until lactation (Fig. 33-3).

FIGURE 33-3. A section from a lactating adenoma, which in this area demonstrates lactational changes that may be seen in normal breast tissue during pregnancy and lactation. Note the marked increase in lobular glandular tissue, secretory changes, and decreased stroma in the lobule.

With hyperplasia, the breasts increase in size. Blood vessels and lymphatic channels proliferate in pregnancy, and there is increased stromal edema (Gupta and associates, 1993). These changes may lead to difficulty in diagnosing breast lesions.

MAMMARY HYPERPLASIA

While the breasts normally increase in size during pregnancy and lactation, massive enlargement occasionally occurs (Eben and colleagues, 1993). This is due to normal but extreme hyperplasia of glands and stroma. Abnormal enlargement usually starts in the first trimester, and often complicates subsequent pregnancies (Beischer and coworkers, 1989). Many different treatment regimens have been used, including testosterone, stilbestrol, corticosteroids, and progesterone (Eben and colleagues, 1993). In nearly all cases, reduction mammoplasty or mastectomy was eventually required to relieve symptoms. Bromocriptine has also been used with successful outcomes (Hedberg, 1979; Turkalj, 1982; and their colleagues). Bromocriptine appears to be well tolerated by the fetus, although there are reports of fetal growth restriction (Briggs and associates, 1990). Although many of these bromocriptine-treated women also required subsequent surgery, some have been treated successfully with bromocriptine alone (Eben and colleagues, 1993).

INFLAMMATORY BREAST LESIONS

MASTITIS

Breast infection may complicate the puerperium in up to 2 percent of women (Stehman, 1990). Although this common disorder usually responds quickly to therapy, it can also lead to significant maternal morbidity if an abscess develops. Occasionally, the reproductive-age woman will present with an inflammatory breast cancer.

The woman with mastitis typically presents 2-3 weeks postpartum complaining of flu-like symptoms, decreased milk secretion, and a swollen, tender area in one breast. Most infections occur within the first 5 weeks of delivery, but may be seen up to 10 months postpartum (Niebyl and associates, 1978). It is not unusual for fever as high as 40°C to occur and for the mother to “feel ill” (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000a). On examination there is erythema, heat, induration, tenderness, and edema in a relatively well-defined area that corresponds to a breast lobule. Axillary nodes may be enlarged, and there usually is leukocytosis with a left shift.

By contrast, breast engorgement is almost always bilateral with generalized involvement and generally occurs in the first 14 days postpartum (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000a). The woman with exquisite tenderness secondary to mastitis may also have engorgement because she has discontinued breast-feeding, but physical findings usually indicate an infection.

Stehman (1990) emphasizes that the best feature to differentiate mastitis from inflammatory breast carcinoma is knowledge of prior breast findings. With normal findings antepartum, a neoplastic process is much less likely, although breast cancer can first become apparent during lactation. Among 103 nonnursing women with inflammatory breast cancer, the mean interval between the first symptom and diagnosis of cancer was 45 days (Bozzetti and colleagues, 1981). These women present with mastitis-like findings with unilateral erythema, heat, and induration; but the process is usually more diffuse. Additionally, the skin is thickened or demonstrates peau d’ orange changes due to tumor involvement of skin lymphatics. There may also be purplish discoloration and satellite nodules. This very lethal form of breast cancer is currently managed by prompt institution of preoperative chemotherapy with follow-up radiation therapy and/or surgery (Jones and Jones, 1990). Biopsy should not be delayed if either a clinical suspicion of inflammatory carcinoma exists or if a woman with mastitis fails to respond to conventional antibiotic therapy. Mammography provides less than optimal information in the lactating breast and is usually not helpful to diagnose inflammatory carcinoma.

EPIDEMIOLOGY. Contrary to older reports, primiparous women are not more predisposed to mastitis (Devereux, 1970). Older literature describes epidemic mastitis and nonepidemic or sporadic mastitis. The epidemic variety was largely staphylococcal and associated with simultaneous manifestations in clusters of hospitalized or recently discharged mothers and infants with the same strains of organisms. In the last 20 years, there have been few reports of such epidemics; however, no explanation is clearly apparent. Because epidemic mastitis was invariably associated with streptococcal or staphylococcal outbreaks in nurseries, improved measures to limit nosocomial infections, as well as earlier discharge may explain why this is seen infrequently today.

Gibberd (1953) concluded that the epidemic variety was secondary to infection of the entire lactiferous system, as opposed to cellulitis involving primarily the breast parenchyma characteristic of the sporadic variety. Because it is the milk and ductal system that is infected in the epidemic variety, the entry point would necessarily be the nipple duct opening; therefore, if bacteria enter several ducts, nonadjacent lobes could be involved as well as the contralateral breast.

The sporadic or nonepidemic variety of mastitis is best characterized as a mammary cellulitis involving periglandular connective tissue. It usually remains confined to a single pyramidal-shaped breast lobule as demarcated by the normal divisions created by Cooper’s ligaments.

There are no known risk factors for the development of mastitis. Even though fissured and chaffed nipples are implicated, the majority of women who are nursing have nipple fissures at some time and do not get infected, just as many women without fissures develop mastitis. Because milk is a good culture medium, it can be hypothesized that anything causing milk stasis may predispose to infection. Stasis may develop from simple engorgement with its attendant edema and decreased egress of milk from ducts secondary to surrounding tissue pressure. Plugging of terminal ducts by epithelial debris can also result in stasis.

MICROBIOLOGY. Exposure to various bacteria occurs from skin colonization, nosocomial bacteria, and the infant’s skin, nose, and oropharynx. The most common organism isolated in acute sporadic puerperal mastitis is Staphylococcus aureus, ranging from 40 to 90 percent (Niebyl, 1978; Schwartz, 1982; Thomsen, 1985; and their colleagues). With improved microbiologic detection methods, a variety of other pathogens have been found, including anaerobic bacteria, coagulase-negative staphylococci, group A and group B streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae and parainfluenzae, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, and Pseudomonas picetti.

Because sporadic mastitis is primarily a subcutaneous cellulitis, it is not surprising that the causative organism is not always cultured from milk. Some authors therefore recommend routine culturing of the infant. Niebyl and colleagues (1978), however, reported no correlation with bacteriologic cultures from milk and infant nasopharyngeal cultures. Only one infant had S. aureus and this organism was not found in the mother’s milk. In contrast, Wysham and coinvestigators (1957) found that similar organisms were cultured from the infant and the mother in all of their cases. Matheson and coworkers (1988a) reported a case of recurrent mastitis secondary to reinfection with S. aureus from the infant’s skin and nostrils.

Staphylococcal species are predominant findings in women with mastitis. Because of their frequent isolation from women with mastitis, Thomsen and colleagues (1985) designed an investigation to examine the pathogenicity of S. epidermis and S. saprophyticus. These human isolates were inoculated into the mammary glands of lactating mice and the glands examined histopathologically. Although no clinical evidence of mastitis was found, 80-90 percent of glands had histologic changes of mastitis. While all lesions healed spontaneously in the mice within a week, several abscesses developed. Using an immunofluorescence technique, these same investigators found the universal presence of antibody-coated bacteria in the milk of women with signs of mastitis (Thomsen, 1982). The only organism identified in 25 percent of these women was coagulase-negative staphylococci.

Contradicting the hypothesis that coagulase-negative staphylococci are pathogens in mastitis was the finding that similar distributions of presumed nonpathogenic bacteria were isolated from the affected as well as the unaffected breast (Matheson and colleagues, 1988a). These investigators also obtained cultures of milk from 100 healthy nursing mothers and the frequency of coagulase-negative staphylococci was similar to that found in women with signs and symptoms of mastitis.

TREATMENT. Timely institution of antimicrobial therapy is important in the management of acute puerperal mastitis. Devereux (1970) reported a 10 percent incidence of abscess formation in 71 cases of mastitis in 53 women treated with antibiotics. Antibiotic therapy was delayed for longer than 24 hours in nine of these women, and six women subsequently developed abscesses. Early therapy in 20 women with clinical findings consistent with mastitis resulted in prompt resolution of symptoms and no abscess formation in the series reported by Niebyl and coinvestigators (1978).

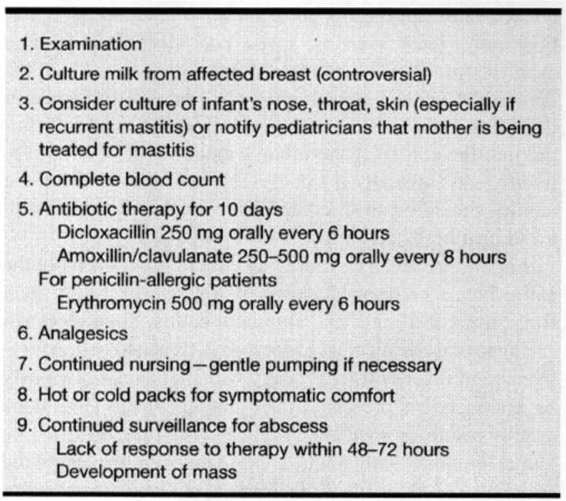

Table 33-1 outlines a conservative approach to the management of the woman with presumed mastitis. Because of the high frequency with which S. aureus is isolated in association with clinical mastitis, most investigators recommend initial therapy with a penicillinase-resistant penicillin such as dicloxacillin. Amoxicillin/clavulanate offers similar S. aureus coverage plus broader spectrum coverage for other organisms, including anaerobes, but its increased cost is probably not justifiable. For penicillin-allergic women who are hospitalized, erythromycin or vancomycin is given intravenously (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000a). If hospitalization is not necessary, then the drug of choice is erythromycin, which achieves concentrations in breast milk that are 50-100 percent of serum concentrations (Graham, 1992). Cefotetan can also be utilized, especially if a penicillinase-producing staphylococcus is isolated (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000a).

TABLE 33-1. Conservative Clinical Approach to Presumed Mastitis

NURSING. Continuation of nursing is important for treatment of mastitis. Many mothers are concerned about passing infection to their infant, but no untoward effects have been reported (Matheson and colleagues, 1988b; Niebyl and associates, 1978; Thomsen and coinvestigators, 1984). Using restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) of total DNA and of ribosomal DNA, Bingen and colleagues (1992) reported five cases of maternal transmission of Streptococcus agalactiae to their neonates via breast milk. All the mothers had postpartum mastitis caused by this organism.

Because antibiotics cross into breast milk, there may be benefit to providing simultaneous treatment of both mother and infant. There is evidence of increased concentration of phenoxymethyl penicillin in the milk of women with mastitis in contrast to healthy controls (Matheson and colleagues, 1988b).

Marshall and colleagues (1975) demonstrated the importance of continued breast-feeding. They reported that the only three abscesses that developed in 65 women with mastitis were among 15 women who chose to wean their infants. Thomsen and coworkers (1984) observed that vigorous milk expression was sufficient treatment alone in half of women with proven mastitis. Early therapy and continued lactation was successful in avoiding abscess formation in all 20 women in the series by Niebyl and coinvestigators (1978).

If the infected breast is too tender to allow suckling, gentle pumping until nursing can be resumed is the best recommendation. Sometimes the infant will not nurse on the inflamed breast. This is probably not related to any changes in the taste of the milk, but is secondary to engorgement and edema, which can make the areola harder to grip. Pumping can alleviate this. If nursing can continue bilaterally, it is best to begin suckling on the uninvolved breast. This allows letdown to commence before moving to the tenderer breast.

Problems with cracked and fissured nipples are most common during the first several weeks of breast-feeding, when the incidence of mastitis is also highest. Several randomized studies failed to demonstrate that any antepartum “nipple preparation” technique or treatment, such as nipple rolling, expression of colostrum, or various creams and ointment, can alleviate this universal problem (Brown and Hurlock, 1975). There are some hygienic measures that can help lessen nipple soreness once suckling has begun. The most important is cleansing the nipple with clean water after each feeding (Niebyl and colleagues, 1978). Encrusted milk can cause significant inflammation and irritation and agents such as soaps and alcohol should be avoided. Additionally, mothers should be instructed on the duration of nursing at each nipple and on proper release of the infant’s grip on the areola and nipple by inserting a finger into the corner of the infant’s mouth. After the nipples fissure, and especially if a coexisting mastitis is present, the nipples should be air-dried and a nipple shield employed to avoid chafing by clothing.

Engorgement can be caused by either failure to empty the entire breast or from blockage of a single excretory duct from inspissated milk and epithelial debris. Such blockage can appear as a segmental process, but, as stated earlier, erythema and fever will be lacking. Nursing should obviously be continued to prevent diffuse engorgement. This alone usually results in spontaneous clearance of the obstruction. Direct pressure with manual expression on the engorged segment, as well as mechanical pumping, may also be helpful. Local warm, wet compresses or prone soaks in a hot tub have also been suggested to soften the breast tissue (Niebyl and coinvestigators, 1978). The most important caveat is to avoid the archaic remedy of binders or discontinuation of breast-feeding.

BREAST ABSCESS

Abscesses can be difficult to detect clinically because they tend to be confined within the normal architectural segments created by Cooper’s ligaments. Thus, the abscess extends or burrows into the underlying breast parenchyma in a pyramidal fashion, and it appears much smaller (Schwartz, 1982). Confinement and associated edema and induration can make evaluation of fluctuance very difficult. Surrounding tissue reaction decreases tissue perfusion and interferes with antibiotic penetration to the abscess cavity. Primary clinical suspicion for an abscess is either failure of mastitis to promptly respond to initial therapy within 48-72 hours or a palpable mass on initial presentation (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000a). Because physical examination can be difficult, imaging with ultrasound using a high-frequency transducer can be helpful to identify an abscess. If doubt remains, aspiration is performed and purulent exudate can be sent for culture and Gram stain. For difficult diagnostic situations there may be a place for magnetic resonance or computed tomographic imaging.

An abscess requires prompt drainage under general anesthesia. Vigorous finger dissection of the loculations caused by parenchymal ligaments is necessary for adequate treatment. The wound should be packed open. If cancer is suspected, a small portion of breast tissue can be sent for histopathology. Radial skin incisions and counterincisions to afford dependent drainage are entities of the past (Stehman, 1990). The incision should correspond to skin lines to achieve a good cosmetic result. This often can be done via a circumareolar incision. Even though the wound will be left to heal via secondary intention, excellent cosmetic results can be achieved as long as drainage has been effected prior to massive tissue necrosis and extension throughout multiple breast lobules. After drainage, frequent dressing changes are employed and antibiotics continued until all evidence of cellulitis and inflammation has subsided.

Breast abscesses are primarily ominous threats to breast integrity and only rarely cause sepsis (Schwartz, 1982). Considerable disfigurement can result if an abscess is not treated early or adequately and spontaneous drainage occurs. Demey and coworkers (1989) reported a case of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) developing in a woman with mastitis 8 days postpartum. Although no mass was seen in imaging during the acute process, computed tomography done for other reasons 3 weeks later disclosed a breast abscess. This was aspirated, but subsequently developed a second abscess 3 months later. Surgical drainage was accomplished with removal of 500 mL of purulent exudate.

UNUSUAL FORMS OF MASTITIS

ANTEPARTUM MASTITIS. There are rare reports of antepartum bacterial mastitis and most are in late pregnancy (Wong and associates, 1986). Presentation, clinical findings, and treatment are identical to that of puerperal mastitis. One of the two women reported by Wong and coworkers (1986) remained febrile and symptomatic for 120 hours after intravenous methicillin had been started. No abscess was ever found with multiple diagnostic techniques. The other patient experienced resolution of symptoms and fever by 4 days.

TUBERCULOUS MASTITIS. Although exceedingly rare in the United States, tuberculous mastitis can pose a diagnostic dilemma and may easily be confused with carcinoma. Women at particular risk are from endemic areas such as India, Africa, or Asia. Alagaratnam (1981) reported 16 women from Hong Kong, of whom one was pregnant and three were lactating. They presented with a tender abscess or persistent, firm mass. Axillary adenopathy was present in half of the patients, and a fourth had evidence of active tuberculosis elsewhere. Another condition that raises suspicion of a tuberculous process is a recurrent abscess that has failed appropriate drainage or one with multiple draining sinus tracts. Diagnosis can be made by biopsy, revealing typical caseating granulomas and Langhans’ type giant cells, or by culture. Differential diagnoses include cancer, abscess, and nonspecific granulomatous mastitis. Most of these tuberculous lesions can be treated by simple excision of the abscess. Simple mastectomy is necessary when the majority of the breast has been destroyed. Antituberculosis drug therapy is given for 18 months.

GRANULOMATOUS MASTITIS. An uncommon granulomatous lesion clinically mimicking breast cancer has been described over the last two decades. This lesion is unique to parous, reproductive-age women. Although a few have been observed in lactating women, there is not a consistent history of breast-feeding. In one series of seven women, all were within 6 years of a gestational event (Fletcher and associates, 1982). Another case was reported in a woman who was 24-weeks pregnant (Macansh and coworkers, 1990). Patients typically present with an enlarging breast mass and axillary nodes, which are not usually enlarged or tender. Most are treated by excisional biopsy because of the clinical impression of carcinoma. Macansh and colleagues (1990) described a woman who was diagnosed using fine-needle aspiration and successfully managed with close observation.

Histopathologically, there is an inflammatory reaction consisting of noncaseating epithelioid granulomas. Foreign-body giant cells and microabscesses are usually identified. Occasionally, multiple granulomas are present, but they are invariably confined to one lobular unit. These lesions can be distinguished from tuberculous granulomas by negative culture, lack of acid-fast bacilli, and noncaseation. The entity is also distinct from plasma-cell mastitis, which has an absolute predominance of plasma cells. Accompanying ductule dilatation and inflammation, squamous metaplasia, and foreign-body giant cells surrounding keratinaceous material suggest that damage to ductule epithelium is from infection or trauma or is chemically induced by secretory material (Fletcher and colleagues, 1982).

While the precise etiology is unclear, older literature suggested that the histologic similarity to granulomatous thyroiditis and orchitis was evidence for an antigen-antibody reaction. Autoimmune hypotheses are further supported by the association with erythema nodosum and resolution with steroid therapy (Adams, 1987; Fletcher, 1982; and their colleagues). These latter investigators found a high incidence of postexcision wound infection in 3 of 5 women, and one developed a recurrent mass requiring reexcision. This lends support to an unidentified infectious agent. Goldberg and colleagues (2000) presented a case of granulomatous mastitis occurring in a 25-year-old pregnant woman at 17 weeks’ gestation. Following poor response to antibiotics and incisional drainage, the mastitis improved with corticosteroid treatment.

BREAST MASSES AND CARCINOMA

Noninfectious breast masses occur relatively infrequently in pregnancy. Any of the various benign and malignant conditions that develop in the nonpregnant breast can be found in pregnancy. Although early investigators suggested that there was a predominance of specific conditions during pregnancy or lactation, more recent studies show that the distribution of general disease categories is similar to that of nonpregnant women.

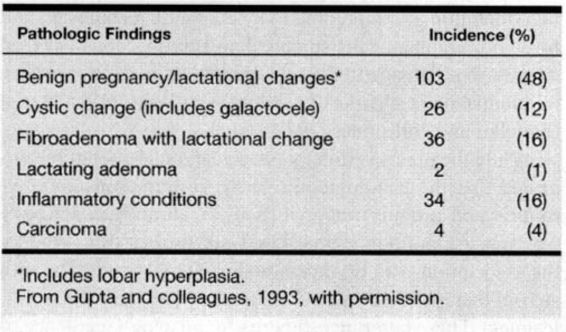

Histologic subtypes of carcinoma are similar in frequency to those in nonpregnant women, although scirrhous carcinomas are more frequent in pregnancy-associated cancer (Ishida, 1992; King, 1985; Dequanter, 2001; and their colleagues). Some abnormalities that are seen much more frequently in the pregnant or lactating woman include galactoceles, lactating adenomas, and fibroadenomas with lactational change (Table 33-2). Awareness of these pregnancy-related benign conditions is important because false-positive diagnoses may be made on cytologic preparations (Finley, 1989; Novotny, 1991; and their colleagues). Importantly, the presence of benign changes does not exclude a malignant process; for example, lobular hyperplasia or mastitis has been reported associated with breast cancer in up to a third of cases (Byrd and colleagues, 1962).

TABLE 33-2. Cause of Breast Masses in 214 Pregnant and Lactating Women

INCIDENCE

Before interpreting reported incidence and prognostic information concerning breast cancer in pregnancy, it is important to be aware that the definition of “pregnancy-associated breast cancer” varies among studies. Some include women in whom breast cancer arises during pregnancy; in some women, the breast cancer predated pregnancy; and in other women, breast cancer was diagnosed up to 2 years after pregnancy. In some series, breast cancer diagnosed postpartum is referred to as “lactational-associated.” The average age of women with pregnancy-associated breast cancer is 35. The youngest reported was 16 years old, and the youngest with disseminated disease was 18 years old.

Although the lifetime incidence of breast cancer in all women is 1 in 9, the actual incidence varies widely by age category according to Survival, Epidemiology and End-Results (SEER) data from the National Cancer Institute (Hankey and colleagues, 1991). Hankey and colleagues cite incidences that range from 1 in 19,600 in women at age 25 years, to 1 in 622 at age 35 years, to 1 in 93 at age 45 years. The incidence then increases significantly in women over 50 years of age and approaches 1 in 30 at age 55 years to 1 in 24 by age 60 years.

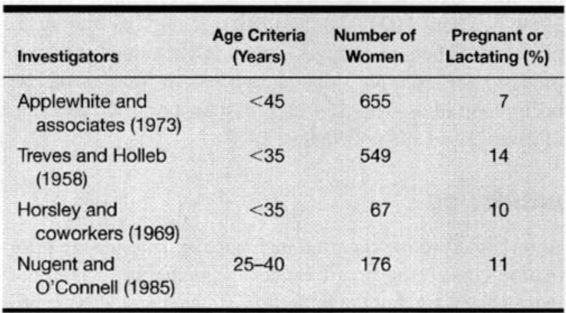

The incidence reported for pregnancy-associated breast cancer is about 10-40/100,000, with approximately 1-3 percent of all breast cancers discovered in pregnant or lactating women (Donegan, 1983; Saunder, 1993; Thierault, 1992; Wallack, 1983; and their colleagues). As shown in Table 33-3, the incidence of pregnancy-associated breast cancer is significantly higher in the childbearing age group, approaching 15 percent. The incidence in premenopausal women may be increasing; thus, there may be an increase in pregnancy-associated malignancies (Gloeckler and coinvestigators, 1987; Saunders and Baum, 1993).

TABLE 33-3. Incidence of Pregnancy-Associated Breast Cancer in Reproductive Age Women

Investigators have also examined the effect of pregnancy on the incidence of subsequent breast cancer, with controversial findings. Lambe and associates (1994) reported a case-control study of more than 12,000 patients. They found that uniparous women had a transiently increased relative risk of developing breast cancer as compared to nulliparous or biparous women, particularly if the first delivery occurred at an age greater than 30 years. After time, this relative increase actually dropped to a relative risk lower than that of nulliparous women. In contrast, Cummings and colleagues (1994), in a case control study involving 2300 patients, found no difference in the incidence of breast carcinoma for any time period after pregnancy when compared to controls.

NATURAL HISTORY AND CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Early investigators concluded that breast cancer in pregnancy was a more aggressive disease with a poor prognosis. Since these earlier reports, numerous studies have demonstrated that survival is similar to nonpregnant women, although there is a significant increase in the proportion of those presenting with advanced-stage disease compared with nonpregnant women. Thus, while pregnancy-associated breast cancer is not a more aggressive disease, pregnant women often experience delayed diagnosis that results in presentation at a more advanced stage (Gemignani and Petrek, 2000). Clark and Chua (1989) reported that 46 of 154 (30 percent) pregnant women and 25 of 96 (26 percent) lactating patients experienced a delay of greater than 23 months. Delay in diagnosis is reported to range from 2 to 15 months and is significant when compared with diagnosis and institution of therapy in nonpregnant women (Ishida, 1992; Zemlickis, 1992; and their colleagues). Delays of 3-6 months have been associated with decreased survival; longer delays have been associated with an increased proportion of women with lymph node metastases at diagnosis (Philiphsen, 1984; Bottles, 1985; Donegan, 1983; Parente, 1988; Vernon, 1985; and all their associates). Employing the use of a mathematical model to estimate the complications of delay in diagnosis, Nettleton and colleagues demonstrated that for tumors with “rapid” doubling times, a delay of 6 months may be associated with a 10.2 percent increased risk of developing nodal metastases (Nettleton and associates, 1996).

Montgomery (1961) reported that while 90 percent of 70 pregnant women detected their own cancer, the physician was responsible for diagnostic delay in 60 percent. Bunker and Peters (1963) reported that more than half of their patients had a delay from detection to diagnosis of more than 6 months. In another study, more than half of women diagnosed postpartum had a breast mass that was followed clinically during pregnancy (Petrek and associates, 1991).

Diagnostic delay is attributed to physiologic changes as well as physician reluctance to use diagnostic tests or to initiate therapy. In many cases, a lump is interpreted as consistent with physiologic change, and as a result evaluation of a questionable mass may be postponed until postpartum. Masses may become artifactually small due to enlargement of the normal breast, giving the erroneous impression the mass is resolving (Lichter and Lippman, 1988). There may be a reluctance to perform a biopsy because of potential hemorrhage, increased risk of infection, and development of milk fistula (Donegan, 1988). Finally, there may be a reluctance to initiate therapy because of potentially harmful fetal effects.

The most important tenet, therefore, is to avoid delay in diagnosis and/or treatment just because a woman is pregnant. This includes avoiding delay in evaluation of self-diagnosed masses or symptoms. Breast self-examination has been shown to be associated with a more favorable stage at presentation and with reduced mortality (Foster and associates, 1992). If there is a low suspicion of malignancy, masses may be observed for a short time (2-4 weeks), and if persistent, they should be further evaluated (Barnavon and Wallack, 1990). Breast cancer is the number one reason for “failure to diagnose” suits among obstetrician/gynecologists (Fiorica, 1992).

In a recent study of pregnancy and “early-stage breast cancer,” Gelber and colleagues (2001) reported that pregnancy did not adversely affect the outcome or prognosis in women with early stage breast cancer.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Benign and malignant lesions of the breast usually present as a mass. Cancers may also be associated with skin changes including thickening, retraction, or fixation; solid masses; surrounding erythema or edema; or persistent crusting of the nipple (Barnavon and Wallack, 1990; Fiorica, 1992). Serosanguineous or bloody nipple discharge is also worrisome, although its most common cause is an intraductal papilloma.

The woman may present with evidence of metastases that include palpably enlarged or knotted axillary lymph nodes, bone pain, pathologic fractures, effusions, or functional visceral abnormalities such as from metastatic disease to the ovaries or gastrointestinal tract. Evans and associates (1992) described a woman who presented with type B lactic acidosis due to metastatic breast cancer at 37 weeks’ gestation.

EVALUATION

The mainstay of breast mass evaluation involves needle aspiration and/or biopsy. As previously emphasized, clinical findings alone should not be used to “follow” a lesion for an extended period. Moreover, masses should not be disregarded until the postpartum evaluation. While the evaluation of cystic masses may be aided by ultrasound, fine-needle aspiration has been used more commonly and has the potential for cytopathologic diagnosis rather than a radiologic impression.

MAMMOGRAPHY/ULTRASONOGRAPHY.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree