19.5 Bone mineral disorders

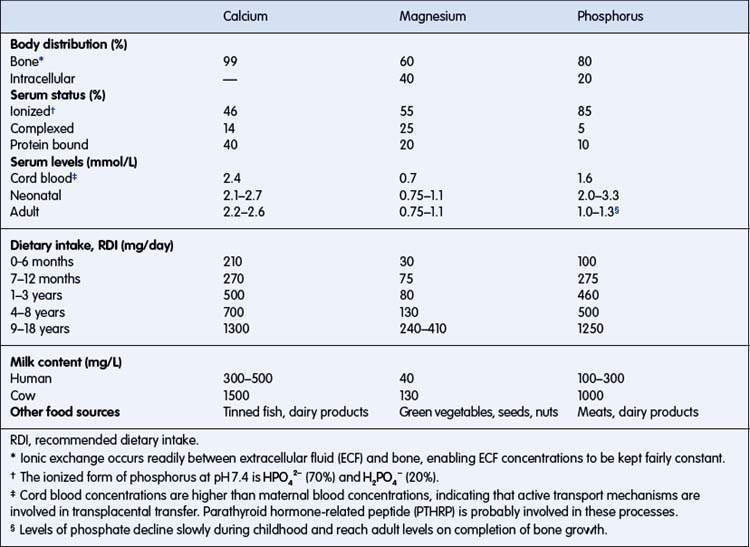

Calcium, magnesium and phosphorus (Table 19.5.1)

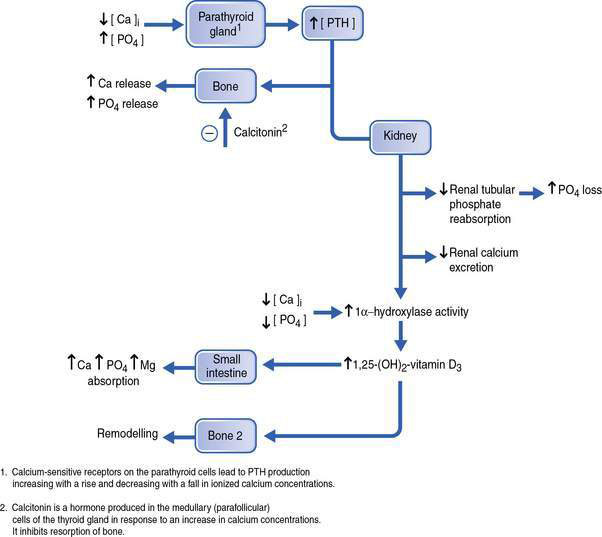

Calcium and phosphate form the major structural components of bone, in the form of hydroxyapatite. The majority of magnesium is also found in bones. A large proportion of each mineral in bone is freely exchangeable with the extracellular fluid (ECF). Calcium and phosphate ions, under normal circumstances, are present in supersaturated solution. A rise in phosphate will lead to the deposition of more calcium phosphate into bone as hydroxyapatite and cause hypocalcaemia. The distribution of calcium and phosphate between bone and the ECF is determined by hormonal regulation of the concentrations of these minerals. The most important hormones are 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (activated vitamin D) and parathyroid hormone (PTH). The actions of these hormones are summarized in Figure 19.5.1.

Table 19.5.1 Distribution, serum concentrations, dietary requirements and sources of calcium, magnesium and phosphate

Kylie, a 6-year-old girl, has nephritis with a metabolic acidosis (pH 7.32, [HCO3−] = 15 mmol/L, Pco2 30 mmHg). She has an albumin of 20 g/L, serum total [Ca2+] = 1.0 mmol/L and serum [phosphate] = 3.6 mmol/L. Is it safe to correct the acidosis with intravenous NaHCO3? From Table 19.5.1, if the serum albumin was normal, 46% of the total serum Ca2+ would be ionized. However, the serum albumin concentration is reduced by 50%, thus the amount of calcium bound to albumin will be reduced by 50% (the proportion of total calcium bound to albumin will be reduced to approximately 20%), leaving the ionized proportion of total serum calcium increased from the normal 46% to approximately 66% = 0.66 mmol/L. Increasing the pH to 7.4 could reduce the ionized portion and precipitate overt symptoms of hypocalcaemia. Thus, the calcium concentration should be corrected before giving NaHCO3.

Hypocalcaemia

Some causes of hypocalcaemia are listed in Box 19.5.1.

Box 19.5.1 Causes of hypocalcaemia

IDM, infant of diabetic mother; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Early neonatal hypocalcaemia is common in premature infants and infants of diabetic mothers. In premature infants, it is possibly an exaggerated response to the normal interruption of the maternofetal calcium transfer; the serum calcium falls following delivery to a nadir, reached at a few days of age, and then increases to normal levels at 1–2 weeks of age. Signs are seen within hours of birth, become most severe about 48 hours after birth and then improve spontaneously. Hypocalcaemia can be aggravated by early phosphate-rich formula feeding or hypoxic–ischaemic injury. Treatment of symptomatic infants involves intravenous (IV) calcium administration and commencement of diet, following the guidelines in Box 19.5.2.

Box 19.5.2 Treatment of hypocalcaemia

Emergency

• Patients with hypocalcaemia and symptoms should be treated with intravenous calcium*

• IV calcium chloride 10% 0.2 mL per kg per dose (max 1 g) repeated 4–6-hourly or followed by infusion 1 mmol (= 1.5 mL 10% CaCl2) per kg per day

• Correct concurrent hypomagnesaemia (magnesium chloride 0.2 mmol/kg over 1 h)

Hypocalcaemia

• Suspect symptomatic hypocalcaemia with tetany, unexplained stridor, irritability or convulsions.

• Confirm diagnosis with total and ionized calcium concentrations and draw blood for estimation of magnesium, phosphate and parathyroid hormone concentrations.

• Treat symptomatic hypocalcaemia with IV 10% calcium chloride 0.2 mL per kg per dose given slowly into a well-placed IV line, and monitor the ECG.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree