Human Papillomavirus-Related Disease

Genital human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted viral infection, is associated with a number of vulvar and vaginal epithelial disorders, including genital warts, vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, and some carcinomas. Of the more than 120 HPV subtypes identified, more than 40 are specific to the anogenital tract, and of those, at least 15 are believed to be oncogenic. Commercially available probes for HPV DNA typing allow for identification of half of these anogenital subtypes, including 5 low-risk and 14 oncogenic subtypes. Although low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 are implicated in the development of genital warts and oncogenic HPV 16 commonly is found in classic (bowenoid) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), routine use of HPV testing for diagnosing vulvar HPV-related disease is not recommended at this time.

Estimates of the prevalence of HPV infection cannot be derived from visible manifestations of disease alone because the majority of infections are subclinical. Approximately 1% of women will develop condyloma, and few will develop dysplasia. Estimates suggest that HPV infection is associated with approximately 40% of vulvar cancers, compared to nearly 100% of cervical squamous cell cancers.

7 In contrast to the typical keratinizing vulvar squamous carcinomas seen in older women (in which oncogenic HPV infection ranges from 2 to 23%), HPV-related basaloid and warty carcinomas (75 to 100% of which are associated with oncogenic HPV) tend to arise in younger women.

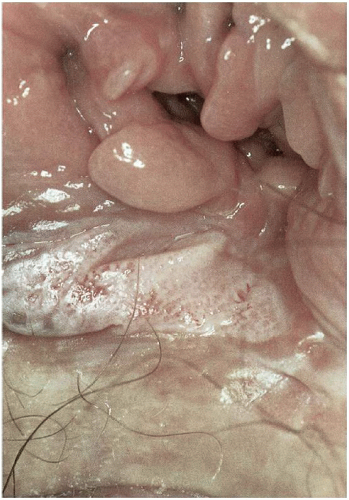

7When clinical manifestations of vulvar HPV infection do occur, they often present as bumps or growths on the vulvovaginal or perianal epithelium. Commonly asymptomatic, genital warts are as likely to cause itching, burning, pain, or bleeding. On examination, warts can range in morphologic appearance from flat-topped papules to flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules, keratotic warts, or true condylomata acuminata (

Fig. 14.2). External genital warts tend to occur on the moist surfaces of the vulva, introitus, and perianal area. Distinguishing warts from vulvar neoplasia based on appearance alone is not always possible. If the diagnosis is uncertain, or the patient is immunocompromised, biopsy should be undertaken.

2Women with genital warts should undergo routine cervical cancer screening. By the same token, the use of HPV testing, a change in the frequency of cervical cytologic screening or cervical colposcopy are not indicated in the presence of genital warts unless exophytic cervical warts or vulvar neoplasia is confirmed by biopsy; in which case, referral for colposcopic evaluation is indicated.

2Spontaneous regression of genital warts occurs in up to 30% of affected patients. Despite this, many women opt for intervention to shorten the duration of lesions. It is important to note that regression does not necessarily lead to viral clearance because viral genomes can be detected in normal epithelium for months to years following clearing of visible disease. In immunocompetent women, however, the cell-mediated immunity that resulted in lesion regression most likely controls latent HPV infection. Disease recurrence is, therefore, less likely. Women at increased risk of developing HPV related manifestations thus include those receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy or chronic immunosuppressive treatment as well as immunosuppressed women with HIV infection. Antiviral chemotherapies are particularly critical for these populations if disease recurrences are to be minimized.

8 However, most currently available treatment options are directed toward removal of visible disease rather than eradication of HPV infection.

Treatments endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention include podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (patient-applied) as well as the provider-administered therapies: cryotherapy, podophyllin resin 10 to 25%, trichloroacetic or bichloroacetic acid 80 to 90%, surgical removal, and laser therapy.

2 Such therapies have been the mainstay of treatment, along with imiquimod, a targeted antiviral therapy. Although most treatments are equivalent in terms of clearance rates, recurrence rates can be high, particularly for laser therapy where the recurrence rate exceeds 60%. However, imiquimod has been demonstrated to have significantly lower recurrence rates (9 to 19%).

7Intralesional interferon, a medication with antiproliferative, antiviral, and immunomodulatory properties, has, unlike imiquimod, demonstrated limited efficacy and is not recommended for first-line therapy in treating either warts or VIN.

8 Its use, however, can be considered an alternative regimen for the treatment of external genital warts.

2 The most recent FDA-approved patient-applied treatment for external condyloma is Veregen 15% topical ointment (Doak Dermatologics, Fairfield, NJ), a class of sinecatechins. This class of drugs is a mixture of catechins and other green tea components and has a response rate up to 55% complete clearance and 78% reduction of external anogenital warts with short-term follow-up.

7Because of decreased immune function, condyloma burden may exacerbate during pregnancy. Treatment is limited to expectant management or locally destructive options. Podofilox, podophyllin, and imiquimod are recognized teratogens and are therefore not recommended for use in pregnancy. Additionally, the risk of HPV appears inconsistent following vaginal delivery and does not justify routine cesarean birth in women with genital warts.

2

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

The most common symptom of VIN is pruritus. The incidence of VIN has increased over 400% since the 1970s especially among younger women.

7 In 2004, the Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Diseases (ISSVD) developed the current classification system for VIN

9 (

Table 14.1). In this classification system, two distinct clinicopathologic subtypes of VIN exist: (a) VIN, usual type, which encompasses the former subcategories of VIN, warty type; VIN, basaloid type; and VIN, mixed (warty, basaloid) type; and (b) VIN, differentiated type, which encompasses the former category simplex type. Previously, VIN was categorized as VIN I, II, and III according to the degree of abnormality. In the new classification system, the term VIN is limited to histologically high-grade

squamous lesions (formerly termed VIN II and VIN III) for which treatment is indicated to prevent progression to cancer.

Usual type VIN, which includes warty-bowenoid or mixed type as well as pure warty and pure basaloid types, includes both VIN II and III, is HPV-related, commonly presents in women in their 30s and 40s, tends to be multifocal, and is strongly associated with cigarette smoking.

10 Risk for usual type VIN is also increased in women who are immunosuppressed or immunodeficient.

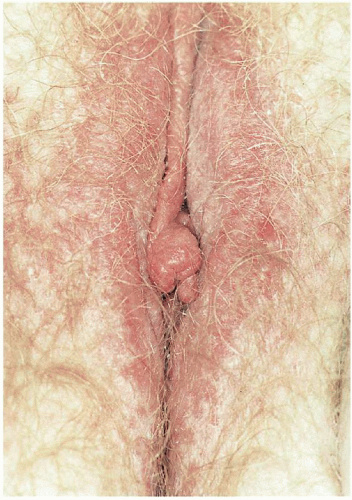

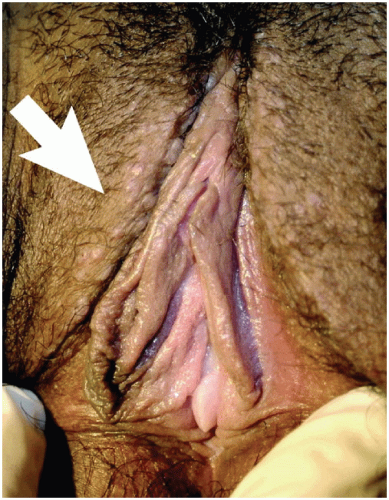

11 The interlabial grooves, posterior fourchette, and perineum are most frequently affected by multifocal lesions and more extensive disease is often confluent, involving the labia minora and majora as well as the perianal skin. Multifocal sites or confluence of usual type VIN is seen in up to 67% of women with usual VIN (

Figs. 14.3,

14.4 through

14.5).

Usual type VIN is more common than differentiated VIN and accounts for at least 90% of cases of VIN. It is strongly HPV associated, with HPV-16 implicated in 70% of cases.

12 Patients often have a history of condyloma, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV-positive status. Less than 10% of women with warty-bowenoid VIN develop invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

13 Younger women with multifocal, small, papular, pigmented lesions (a clinical entity referred to as bowenoid papulosis;

Fig. 14.6) are the most likely to experience spontaneous resolution of the lesions, particularly if they are pregnant or postpartum at the time of diagnosis.

14 In contrast, women older than 40 years of age and those who are immunosuppressed are at the greatest risk of progression.

Differentiated VIN, which includes simplex VIN, is typically HPV negative, is seen most frequently in older women with other epithelial disorders such as lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus and is usually unifocal and unicentric. Although simplex VIN accounts for only 2 to 10% of biopsy specimens with VIN, it is more likely to progress to SCC than classic VIN. In one review looking at the natural history of differentiated VIN, 9% of untreated patients progressed to invasive vulvar carcinoma compared to 3.3% of treated patients.

15,16 Differentiated VIN often occurs adjacent to invasive

SCC of the vulva and is thus regarded as the most common precursor to vulvar SCC. It may be often underdiagnosed.

17 By definition, simplex VIN is a high-grade lesion and warrants further evaluation and treatment. In general, differentiated VIN lesions are smaller and less bulky than warty-baseloid VIN lesions, and often appear as gray-white lesions with roughened surfaces or as raised white plaques or nodules. It is often found during surveillance examinations for women with a history of lichen sclerosus or vulvar SCC. All suspicious lesions of the vulva should be biopsied.

VIN is highly variable in its gross appearance; because the lesions may be subclinical, they may only be apparent with colposcopy. Because the prevalence of multifocal lesions is high, comprehensive colposcopic examination of the entire lower genital tract and perianal area is indicated in any woman with VIN. The most common findings noted on the vulva during examination with the colposcope are areas of acetowhitening that may or may not have areas of punctation. When using colposcopy to evaluate for VIN, it is important to remember that the vulvar area must be soaked with 2 to 5% acetic acid for about 5 minutes. Acetowhite changes do not determine the diagnosis; rather, they are nonspecific and only serve to indicate where biopsies should be taken. Raised acetowhite areas, particularly in conjunction with small papillations or satellite lesions, suggest HPV changes. Lesions that are hyperpigmented, fixed, indurated, or ulcerated, as well as condylomas that do not respond to therapy warrant biopsy evaluation. Vulvar punch biopsies are usually done with the Keys dermatologic biopsy instrument because it allows for full-thickness evaluation of the vulva skin as well as accurate orientation of the specimen. Multiple biopsies may be required when there are multifocal lesions. Bleeding from the biopsy site is usually controlled with ferric subsulfate (Monsel solution) or silver nitrate sticks; rarely are sutures necessary. If a punch biopsy does not yield a satisfactory specimen or if the lesions are quite indurated or have extensive ulceration, an excisional biopsy may be needed. If melanoma is suspected, excisional biopsy is indicated. Any lesion on the vulva that is not known to be benign warrants a biopsy, and if there are multiple areas of abnormalities, multiple biopsies are indicated.

The goals of treatment for VIN are to prevent the development of invasive vulvar cancer and alleviate symptoms, without marked changes in the normal anatomy and function of the vulva. Treatment is individualized, with consideration of the biopsy results, location and extent of the disease, and the patient’s symptoms. Observation suffices for VIN I. For patients with VIN II or VIN III, treatment usually is recommended, although observation is initially reasonable for women who have recently completed a course of corticosteroids, who are temporarily immunocompromised, or who are pregnant.

Management options currently include wide local excision, skinning vulvectomy, laser ablation, and topical treatment. Wide local excision or laser therapy for patients with no evidence of gross or microscopic invasion remains the primary treatment used for VIN. The surgical approaches for treatment appear to be similarly effective.

16 Treatment should go to a depth of 1 to 2 mm in non-hair-bearing areas and may need to extend to 3 mm in hair-bearing areas of the vulva in order to encompass any disease around the hair follicle. Disease-free margins of at least 1 cm should be excised around the lesion.

Topical agents that enhance or induce strong cell-mediated immune responses likely hold the greatest promise not only for control of HPV-related disease but also for reduction of future recurrences. Prior to the use of topical treatments, a careful colposcopic examination with biopsies must be done to rule out invasive disease. Topical 5% imiquimod acts by activating macrophages and dendritic cells to release interferon and other proinflammatory cytokines. These cytokines in turn lead to activation of the appropriate antigen-specific immune response. Imiquimod efficacy in the treatment of genital warts is well documented, and in a number of recent trials, its use has been associated with encouraging results in the treatment of VIN II and VIN III with a response rate approaching 90%.

15,18,19 Furthermore, van Seters found regression of VIN was associated with clearance of HPV.

19 Imiquimod has been associated with relief of pruritus and pain both immediately and for up to 12 months after use.

19 Side effects of imiquimod are usually local and may include mild to moderate erythema, erosion, burning, and ulceration.

Current treatments for VIN, although numerous, have largely resulted in suboptimal outcomes. Response rates have been poor and relapse rates high. Additionally, the resultant physical and psychological morbidity associated with treatment can be profound.

At least one-third of patients develop recurrent VIN regardless of the prior treatment modality. Risk factors for recurrence include immunosuppression, multifocal or multicentric disease, and positive margins on the biopsy specimen. For this reason, patients treated for VIN should be followed closely every 3 to 4 months until they are disease free for at least 2 years.

Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasm

Although the true incidence of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasm (VAIN) is not known, the diagnosis has been increasing over the last several years due to increased awareness, expanded cytologic screening, and more liberal use of colposcopy. The average patient is between 43 and 60 years of age. Infection with HPV is a common association.

VAIN is the terminology used to describe vaginal dysplasia. This spans the spectrum from VAIN I and II (only the lower one-third and two-thirds of the epithelium, respectively, is involved) to VAIN III (more than two-thirds of the epithelium is involved). Full-thickness involvement of the epithelium, or carcinoma in situ, is included under VAIN III. VAIN is consistently associated with prior or concurrent neoplasia elsewhere in the lower genital tract.

Premalignant neoplasms are almost always asymptomatic and are often detected by an abnormal Pap smear, although some patients may present with postcoital spotting or vaginal discharge. A tissue diagnosis must be established when an abnormal cytologic smear of the vaginal cuff is obtained. Colposcopy is performed with biopsy of the most abnormal area. If there is any question of invasion, excision under anesthesia must be undertaken. In postmenopausal patients, a few weeks of topical estrogen may help visualization and improve detection of VAIN.

After application of acetic acid, lesions often appear as raised or flat white, granular epithelium with well-defined borders; punctuation may or may not be present. Biopsies should be taken of any abnormal appearing areas. It may be helpful to slightly close the speculum prior to biopsy so the vaginal wall is not taut with tension, which makes performing a biopsy difficult. Local anesthetic (without epinephrine) should be used prior to biopsy. The choice of biopsy instrument depends on the type and location of the lesion. Sessile lesions may usually be biopsied with cervical biopsy forceps, whereas some raised lesions may be grasped with a forceps and affine scissors maybe sued for biopsy. The majority of lesions are in the upper one-third of the vagina, so in patients posthysterectomy, they may be difficult to see and skin hooks may be needed to evert areas of vaginal wall recess. If the surface is irregular or there are severe vascular abnormalities, an excisional biopsy should be taken to exclude an invasive process. Hemostasis can usually be obtained with ferric subsulfate (Monsel solution) or silver nitrate; in some cases, a suture may be necessary.

A variety of treatment options are available for VAIN: excision, ablation, topical chemotherapy, and radiation. Management should be individualized with consideration given to the presence of multifocal disease, any history of previous treatment failures, the woman’s general health and risks from surgery, her desire to preserve her sexual function, and the degree to which the provider is sure that invasive disease has been ruled out. Some manage VAIN I with close surveillance. In general, surgical excision is the most common form of VAIN treatment. This may require local excision, partial vaginectomy, and rarely, total vaginectomy. Ablation is most commonly done with the CO

2 laser, and up to one-third of patients may need more than one treatment. There are no guidelines clearly defining the ideal topical treatment for multifocal high-grade VAIN, although it appears to

be appropriate first-line therapy for women with early lesions and multifocal disease or those who are poor surgical candidates. Imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil are the topical agents most commonly used. Radiation therapy is reserved for patients who have failed previous treatments for VAIN; are poor surgical candidates; or have extensive, multifocal disease. Because VAIN is usually multifocal, follow-up every 6 months for up to 2 years and then annually thereafter is warranted.

Extramammary Paget Disease

Extramammary Paget disease is an uncommon lesion that arises in skin rich in apocrine glands, with limited information based on case reports and case series owning to its rarity. Vulvar Paget disease is most often an apocrine carcinoma in situ. However, 4% of women will have a contiguous adenocarcinoma and up to 26% will have noncontiguous underlying adenocarcinoma.

20,21 Patients characteristically present with symptoms including burning or itching, with a reported age range of 47 to 93 years in one case series.

22 The classic appearance of vulvar Paget disease is a red velvety plaque, which may be mistaken for vulvar eczema (

Fig. 14.7). It is usually multifocal and may occur anywhere on the vulva, mons, perineum/perianal area, or inner thigh. Vulvar biopsy should be performed in patients with suspicious lesions, including those with persistent pruritic eczematous lesions that fail to resolve within 6 weeks of appropriate antieczema therapy.

Paget disease is diagnosed by histologic appearance including the presence of signet-ring or Paget cells. Following biopsy confirmation of vulvar Paget disease, patients should be screened for possible associated or synchronous cancers with pelvic exam, cervical cytology, endometrial biopsy, and mammography, as well as targeted evaluation for anal (occult blood testing, endoscopy) or urethral (urine cytology, cystoscopy) lesion involvement given the risk for underlying adenocarcinoma.

22Treatment of noninvasive Paget disease is classically by surgical excision with limited evidence for nonexcisional treatment modalities such as laser ablation, radiotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and imiquimod. The risk of recurrence following excision is reported to occur in up to 60% of women regardless of margin status or extent of surgery and is attributed to the presence of “skip lesions.”

22 The use of frozen section to ensure complete excision (negative margin status) has been employed to reduce the high rate of recurrence without clear benefit. Given the risk of recurrence and progression to invasive disease, long-term monitoring with biopsy of any abnormal vulvar lesion is paramount in patients with a history of Paget disease.