Basic Orthopedics

Kathryn B. Leonard

Christopher P. O’Boynick

Robert M. (Bo) Kennedy

MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA

Fractures

In general, ligaments in children are functionally stronger than bones. Therefore, children are more likely to sustain fractures than sprains. The physis (growth plate) is a cartilaginous structure at the ends of long bones that is generally weaker than the surrounding bone and is therefore predisposed to injury.

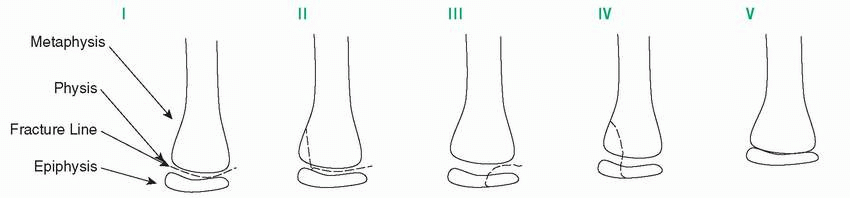

Fractures through the physis can be classified using the Salter-Harris system (Table 6-1).

Type I: Fracture through the physis that separates the metaphysis and epiphysis. These are often difficult to appreciate radiographically and are diagnosed clinically when point tenderness is found over the growth plate.

Type II: Fracture extends through the physis and into the metaphysis.

Type III: Fracture extends through the physis and epiphysis into the intra-articular space.

Type IV: Fracture involves the epiphysis, physis, and metaphysis.

Type V: This is a crush injury of the physis resulting from axial compression and is often difficult to diagnose radiographically.

In general, the prognosis for normal healing worsens as the classification increases.

Evaluation

The examination of any patient with suspected fracture should address the “5 Ps.”

Point tenderness

Pulse distally

Pallor

Paresthesia distally

Paralysis distally

Radiographic evaluation usually should include the joint above and below the fracture and at least two views of the injured region (generally anteroposterior and lateral).

General Management

Keep patients nil per os (NPO) in case sedation or surgery is required.

Cover open wounds with a sterile dressing. Open fractures require tetanus prophylaxis, antibiotics, and urgent débridement in the operating room (OR).

Early pain management involves splinting and analgesia, for example, oral oxycodone 0.2 mg/kg.

The need for closed reduction is multifactorial and related to patient age (potential for remodeling), bone(s) involved, and angle(s) of displacement.

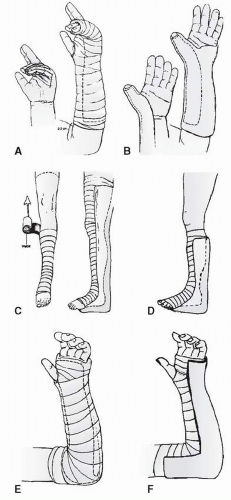

Closed reduction can be accomplished under sedation, followed by immobilization with a splint or bivalved cast (Fig. 6-1). Casts or splints should encompass the joint proximal and distal to the site of the injury.

Open reduction in the OR is indicated in failed closed reduction, displaced intraarticular fractures (Salter-Harris types III and IV), unstable fractures, and open fractures.

After placement of a cast, it is important to monitor for signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome, again described by the “Ps”:

Pain out of proportion to the injury or pain with passive movement of fingers/toes (earliest sign)

Paresthesias distal to the cast

Pallor or cyanosis of the extremity distal to the cast

Pulse weak or thready distal to cast

Other signs include: Marked swelling of tissues distal to the cast/increasing agitation and/or analgesia requirements

TABLE 6-1 Types of Salter-Harris Fractures | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Concerns Related to Nonaccidental Trauma

While no fracture is pathognomonic, certain types and patterns of fractures should raise the clinician’s suspicion for nonaccidental injury. When considering a pediatric patient who is younger than 3 years of age and nonverbal, the following fractures should raise suspicion for child abuse, particularly if an implausible or inconsistent history of injury is provided.

Multiple Fractures

A patient who is younger than 3 years of age and presents without a plausible mechanism of injury needs a complete skeletal survey to evaluate for the presence of additional fractures.

Multiple fractures that are unaccounted for in the history should generate a reasonable suspicion for nonaccidental trauma.

Fractures in various stages of healing should be concerning for repeated injury.

Complex Skull Fractures

These skull fractures contain more than one line of fracture, sometimes described as a stellate pattern, and they may be accompanied by displacement or diastasis.

Most accidental injuries are the results of falls onto a flat surface with resultant linear fractures over the convexity of the skull. The presence of a complex skull fracture implies a greater level of force applied to the skull than is usually expected in a short fall onto a flat surface (i.e., off a bed or couch onto the floor).

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures may be present posteriorly, laterally, or anteriorly along the rib shaft.

Posterior rib fractures are most often associated with anteroposterior-directed thoracic compression.

Lateral and anterior rib fractures may also occur after such squeezing. These fractures also occur from direct blows to the chest.

Look closely at the ribs above and below the known fracture because a direct blow often fractures several ribs simultaneously. The addition of oblique views increases the ability to detect rib fractures in cases of suspected abuse.

Classic Metaphyseal Lesions (“Corner Fractures” or “Bucket-Handle Fractures”)

Think of these as avulsion fractures at the growth plate, in which either a crescent (bucket handle) or fragment (corner) of bone is torn from the zone of provisional calcification and contained by the periosteum.

These generally result from pulling or twisting forces.

These injuries generally are not acute and represent previous injury to the physis.

Humerus Fractures

These are the most common long bone injuries associated with abuse, particularly in children <3 years of age.

Femur Fractures

These are the second most common fractures seen in child abuse, and are extremely suspicious for abuse in a nonambulatory child without plausible mechanism.

UPPER EXTREMITY MUSCULOSKELETAL INJURIES

Clavicular Fracture

This is the most frequent fracture in children. It may occur as a result of birth trauma, falling onto an outstretched arm, or direct trauma to the shoulder.

Treatment:

Most fractures are treated nonoperatively with a sling ± swathe, with bony union expected at 2-4 weeks.

Surgery is reserved for open fractures, fractures with associated neurovascular injury (especially fractures near the sternum with posterior displacement), and fractures that compromise the skin (tenting).

Shoulder Dislocation

These are less common in the skeletally immature as most injuries tend to produce fractures. When shoulder dislocation does occur, 90% are anterior dislocations.

Findings on exam include obvious deformity with loss of the usual rounded contour of the shoulder and significant pain with limited range of motion.

Closed reduction should be performed, followed by post-reduction radiographs to ensure that there is no associated fracture. An axillary lateral x-ray is required to confirm reduction.

Patients should be immobilized in a sling and swathe and referred for orthopedic follow-up.

Recurrence is common, with an incidence of 50%-95% and a greater rate of recurrence associated with younger age at first dislocation.

Proximal Humerus Fracture

The majority of these fractures will remodel and can be managed with a sling and swathe for 2-4 weeks (no splint or cast required) and referred for close orthopedic follow-up.

In children <12 years old with Salter-Harris type I or II fractures, up to 40 degrees of angulation and displacement of one-half the width of the shaft may be acceptable and treated as described above. In adolescents, 20 degrees of angulation and displacement <30% the width of the shaft may be acceptable.

Elbow Injuries

Elbow injuries are common in children. Orthopedic consultation is necessary for most.

A careful neurovascular examination to evaluate for distal pulses, capillary refill, and motor/sensory function of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves is essential, as neurologic or vascular compromise (usually transient) can be present with these injuries.

On radiographs of the elbow, special attention must be made to the following:

Anterior humeral line: On lateral views of the elbow, this line should intersect the middle third of the capitellum to rule out posterior displacement of the distal humerus.

Radiocapitellar line: A line drawn through the middle of the radial head should intersect the center of the capitellum. Failure of this line to intersect with the center of the capitellum indicates radial head dislocation.

Posterior fat pad sign: This lucency posterior to the distal humerus is generally visible on in the setting of moderate to large joint effusions. Fractures are present >70% of the time when a posterior fat pad is seen on x-ray.

Anterior fat pad sign: Elevation of the anterior fat pad is called the “sail sign” and indicates an effusion. This too suggests possible associated fracture.

If no fracture is seen on the lateral x-ray, and the capitellum is not posteriorly displaced, but a posterior fat pad is present, apply a long-arm posterior splint and refer to orthopedic surgery for follow-up.

Common elbow injuries include supracondylar humerus fractures, lateral condyle fractures, medial epicondyle fractures, and elbow dislocations.

Supracondylar Humerus Fracture

These account for the majority of elbow fractures in children. They generally occur after a fall onto an outstretched arm with hyperextension of the elbow or direct trauma.

Treatment is dependent on the degree of displacement of the fracture:

Type I: Nondisplaced. Treated with immobilization in a long-arm cast or posterior splint with the elbow flexed at 60-90 degrees

Type II or III: Displaced fractures require orthopedic consultation and may need to be treated with closed reduction, pinning or open reduction, and internal fixation if unstable.

Radial Head Subluxation (“Nursemaid’s Elbow”)

This injury generally occurs in children younger than 5 years of age and is often the result of excessive axial traction on an extended elbow.

The classic history is a child who cries with pain and refuses to use the arm after being pulled or lifted by that arm. The child tends to hold the arm pronated and slightly flexed at the elbow and refuses to supinate or pronate the wrist. There is sometimes slight tenderness over the radial head.

Note that radial head/neck fractures may mimic nursemaid’s elbow. History and careful exam for areas of significant point tenderness and swelling are very important.

Radiographs are unnecessary if reduction is successful. If x-rays are obtained, positioning of the arm for multiple views often results in reduction.

Reduction is performed by quickly and fully supinating or pronating the wrist, followed by flexion of the elbow; a “pop” is felt over the radial head at the elbow.

The patient will use that arm normally within 5-10 minutes. If there is no evidence of recovery, the diagnosis should be reconsidered.

Forearm Fractures

Fractures of the radius and ulna are extremely common in children. The majority of these fractures involve the distal forearm.

Colles fracture: Fracture of the distal radius with displacement, resulting in classic “dinner fork” deformity of the wrist.

Buckle fractures of the distal radius or ulna are treated with a wrist splint if pain on supination/pronation is minimal. If a parent is concerned the child will not leave the splint on, or if there is significant pain with movement of the wrist, a sugartong splint can be applied.

Fractures of one or both cortices should be immobilized in a long-arm posterior or sugar-tong splint to immobilize the elbow and prevent pronation and supination.

Fractures with displacement or angulation are unstable and require reduction followed by immobilization as above.

Fractures of the radial and ulnar shafts deserve special mention:

The potential for remodeling decreases in the diaphysis and in older children. Very little angulation is acceptable, and most of these injuries require orthopedic referral.

The thick periosteum of the radius and ulna contributes to greenstick or bowing fractures, which must be recognized and referred to an orthopedic specialist due to limited potential for remodeling with these injuries.

When isolated fractures of the ulna or radius occur, careful review of images of the elbow and wrist is important to rule out associated dislocation patterns:

A Monteggia fracture is an ulnar fracture with associated radial head dislocation.

A Galeazzi fracture is a radial shaft fracture with disruption of the radioulnar joint distally.

Hand Fractures

Scaphoid Fracture

This is the most common carpal bone fracture and typically occurs in adolescents. It generally occurs with direct trauma or falling onto an outstretched arm with hyperextension of the wrist.

Characteristics include wrist pain and swelling, snuffbox tenderness, pain with supination against resistance, or pain with longitudinal compression of the thumb.

Radiographs may be normal, even with dedicated scaphoid views. If physical findings suggest a scaphoid fracture (despite normal radiographs), treatment should include:

Thumb spica splint or cast

Orthopedic follow-up is a must for these injuries whether confirmed or suspected.

There is a risk of malunion or avascular necrosis with these fractures, although this is less common in the pediatric population, it can be devastating if missed.

Boxer Fracture

This is a fracture of the fifth metacarpal with apical dorsal angulation. It generally occurs after an object has been struck with a closed fist.

Assess for malrotation by having the patient flex his/her fingers to make a fist and evaluate for overlapping of the fingers (“scissoring”). The malrotation should be reduced before placement of an ulnar gutter splint.

Treatment:

Attempts at closed reduction are usually ineffective since these fractures are unstable. Place an ulnar gutter splint (see Fig. 6-1) with the metacarpals flexed at 70-90 degrees, and refer to a hand surgeon for consideration of operative pin insertion for stabilization, especially those with angulation >30-40 degrees.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree