Michael R. Foley, MD

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a maternal medical condition that can have a profound impact on pregnancy. The incidence of asthma in pregnancy makes it a common comorbidity that a practitioner will encounter and the most common respiratory disorder found in pregnancy. Asthma affects approximately 4% to 8% of pregnant women and the prevalence seems to be increasing.1 The range of severity and high prevalence of the condition can make it an overlooked part of the medical history, even though it can become a life-threatening condition.

The general rule for asthma in pregnancy has been that one-third will improve, one-third will worsen, and one-third will remain stable. A recent study has disproven the latter. Instead, two factors significantly impact the course of the disease throughout pregnancy: pre-pregnancy severity, specifically in the 1 year before pregnancy, and adherence to medications prescribed according to Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines. Patients who discontinue or are noncompliant with therapy will be more likely to worsen, even if their initial classification is less severe.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The initial history of asthma should be elicited before conception or at the first prenatal visit. For those who do not carry a diagnosis of asthma, certain components of the history and physical exam can lead to a clinical suspicion for undiagnosed asthma. History of a chronic cough, which is typically worse at night, wheezing, chest tightness, or difficulty breathing, can be initial symptoms. Exercise, viral infections, pets, dust, smoke, and other irritants that trigger or worsen symptoms should prompt a provider to consider a diagnosis of asthma. Wheezing heard on lung exam is a common sign, although is not necessary for the diagnosis. Any of these findings can heighten clinical suspicion and a provider can consider obtaining pulmonary function testing to establish the diagnosis.3

Asthma exacerbations typically present with an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms, including cough, wheezing, chest tightness, and dyspnea. A 20% decrease in peak expiratory flow (PEF) may be seen on spirometry. A subjective decrease in fetal movement can be an early symptom of an asthma exacerbation.4 Asthma exacerbations are more common in noncompliant patients or patients with persistent asthma. One study found that exacerbations requiring medical intervention occurred in almost 5% of pregnancies complicated by asthma, although other studies have estimated as many as 36% of patients had exacerbations.5 Exacerbations were more common in women who had more severe asthma. This study did not find that any trimester was associated with an increased risk for exacerbation.5

DIAGNOSIS

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition because of interactions of inflammation, airflow obstruction, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Allergens and respiratory infections are important contributors to the development and persistence of asthma. Asthma is clinically diagnosed by the presence of intermittent airflow obstruction or airway hyperresponsiveness that is at least partially reversible, while excluding other causes.3 The diagnostic criteria of asthma are the same as for nonpregnant patients.6 A thorough history and physical exam should be completed. Pulmonary function tests can be helpful. In asthma, spirometry shows an obstructive pattern characterized by a decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC). Reversibility should also be seen, which is demonstrated by an increase in FEV1 of 12% or greater and greater than 200 mL from baseline after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator.3 Baseline values for FEV1 and FVC should not significantly change during pregnancy.4

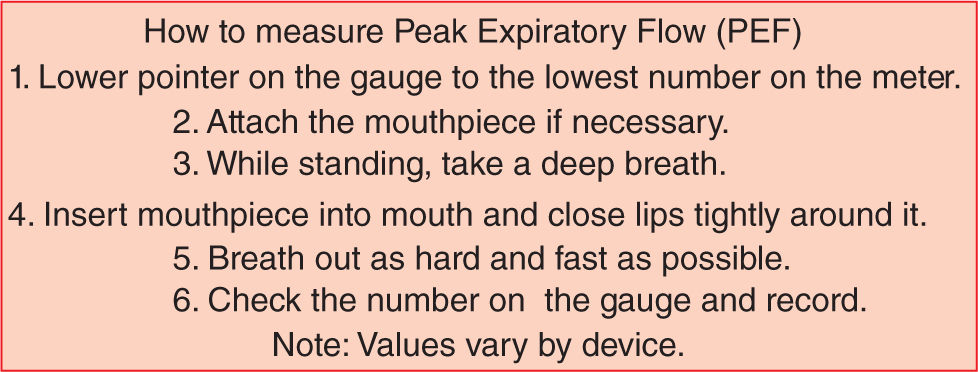

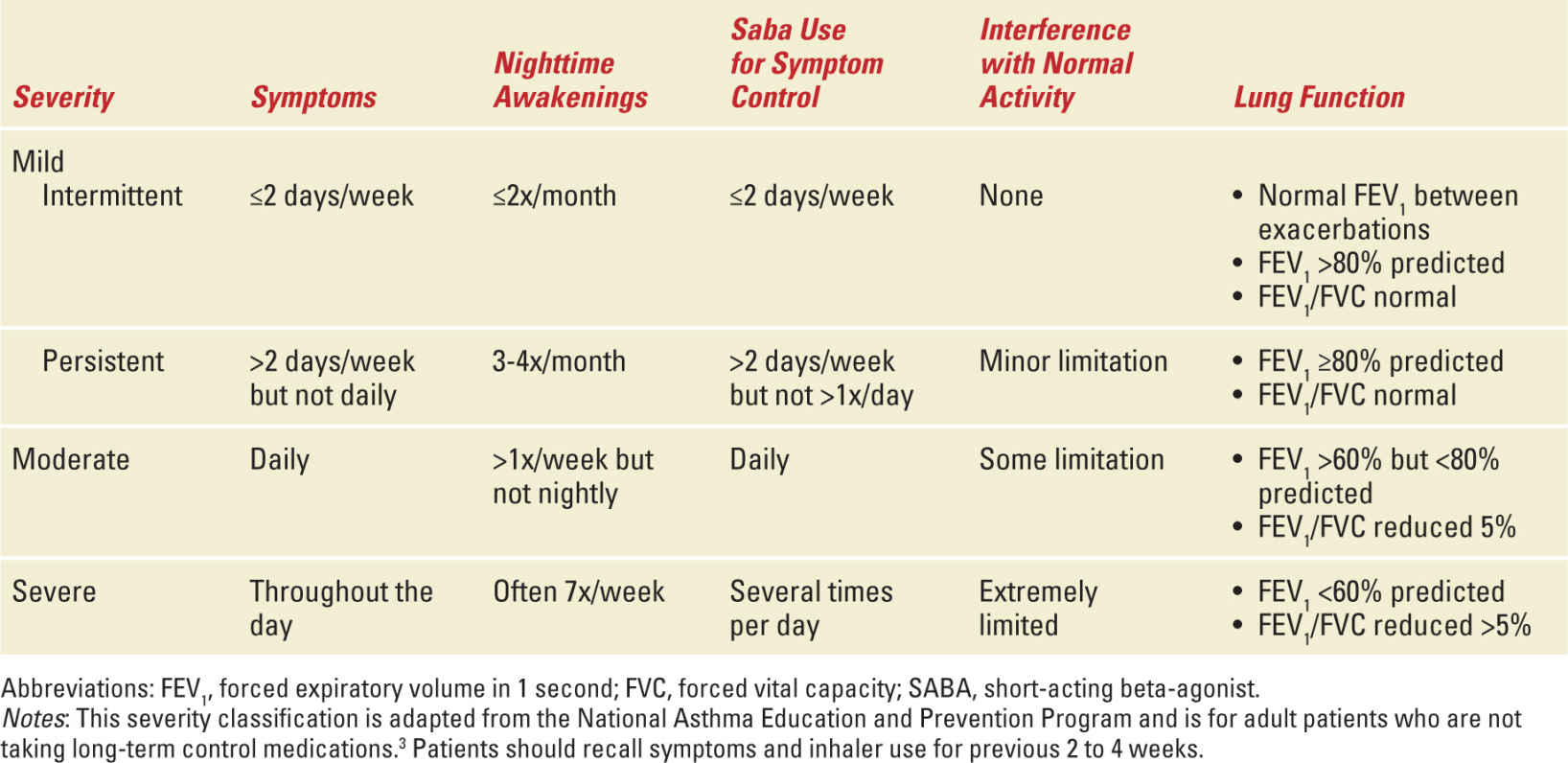

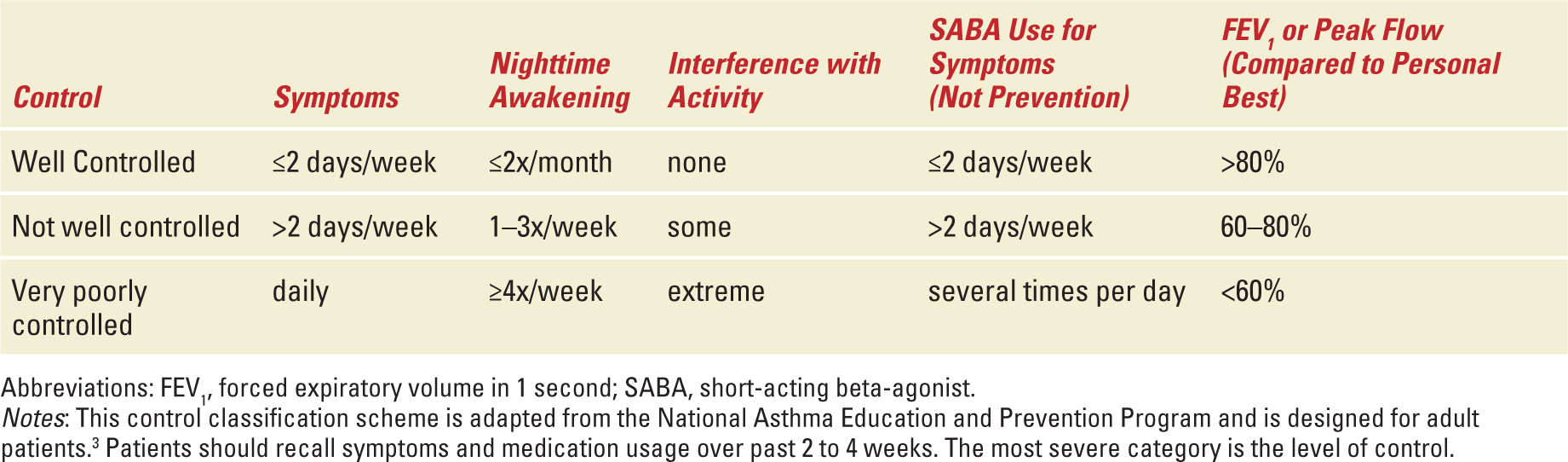

Once the diagnosis is established, triggers, allergens, and comorbidities should be evaluated. Common triggers include pets, mold, occupational exposures, and tobacco smoke. Comorbidities that can contribute to asthma include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea, and sinusitis. The treatment of identified comorbidities should be optimized. Patients should be provided with a PEF meter and instructed on its use and utility (Figure 10-1). The severity of asthma should be qualified.3 Current levels of severity and their definitions can be found in Table 10-1. Control of asthma once on medications can be determined using many of the same variables. Levels of control can be found in Table 10-2. Well-controlled asthma predicts risk of 0 to 1 exacerbations per year, whereas not well-controlled or very poorly controlled asthma predicts risk of 2 or greater exacerbations per year.3

FIGURE 10-1. How to use a peak expiratory flow meter. This step-by-step guide is used to instruct patients on the correct use of a peak expiratory flow meter to get an accurate and reliable value. The peak expiratory flow meter should be used to monitor symptoms and treatment at home as well as in both inpatient and outpatient care settings.

Asthma Severity Classification |

Asthma Control Classification |

It is important to recall the normal physiologic respiratory adaptations anticipated for pregnancy when evaluating laboratory values and pulmonary function testing. Oxygen consumption increases up to 20% as a result of increased cardiac output and minute ventilation. Tidal volume and inspiratory capacity are also increased. Respiratory rate, vital capacity, and inspiratory reserve volume are unchanged. Other variables, including residual volume and functional residual capacity, are decreased. These changes result in a chronic, compensated respiratory alkalosis in pregnant women, which impacts interpretation of arterial blood gas values.7

MANAGEMENT

Outpatient

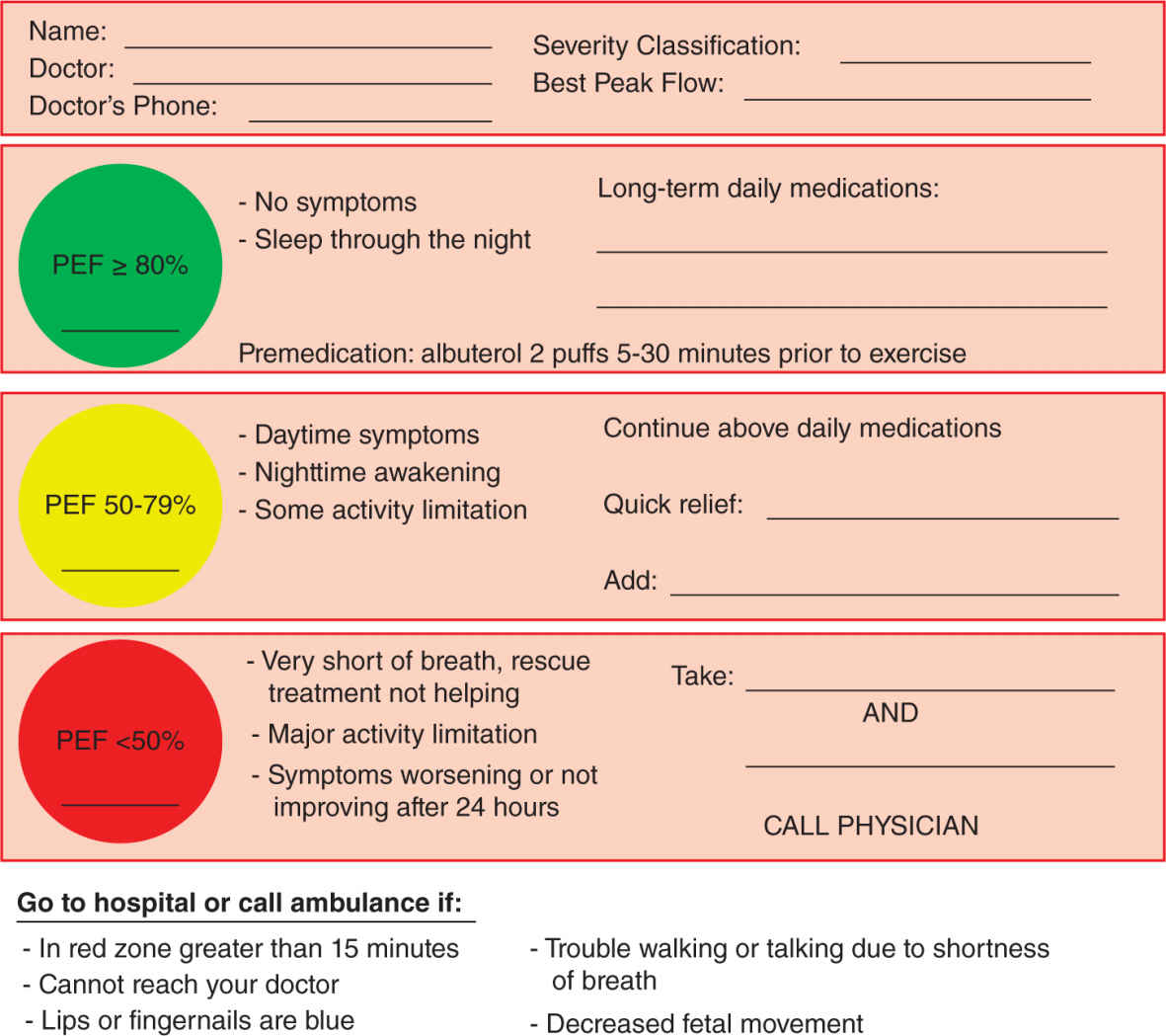

Education and patient compliance are at the forefront of outpatient asthma management. Smoking cessation is an integral part of asthma care and referral to cessation counseling is appropriate. Patients should be seen at least monthly to monitor symptoms and treatment. Monthly visits should include assessment of symptoms and control, compliance and use of medications, lung exam, and pulmonary function. At the initial pregnancy visit, spirometry is recommended. At routine follow-up visits, PEF is acceptable. Ultrasound monitoring of the fetus is considered starting at 32 weeks for women with suboptimal control and for those women with moderate to severe persistent asthma. An ultrasound assessment should also be considered when treating acute exacerbations.4 An individualized asthma action plan should be given to each patient (Figure 10-2).

FIGURE 10-2. Asthma action plan. This is an example of an asthma action plan that can be completed and customized for any patient. Their demographics should be completed to ensure a known baseline peak expiratory flow and good contact information for their physician. The green zone is when a patient is taking their prescribed long-term daily medications with no need for rescue therapy. The patient begins yellow zone therapy with increased symptoms. She should add a short-acting β2-agonist for quick relief and can add an oral corticosteroid. If the symptoms persist or worsen, she should again take a short-acting β2-agonist and a higher dose oral corticosteroid and call her physician for directions. With any serious concern, the patient should be instructed to present to the emergency department or call an ambulance. This guide allows the patient to be informed and ideally escalate early outpatient treatment before needing hospitalization. PEF, peak expiratory flow.

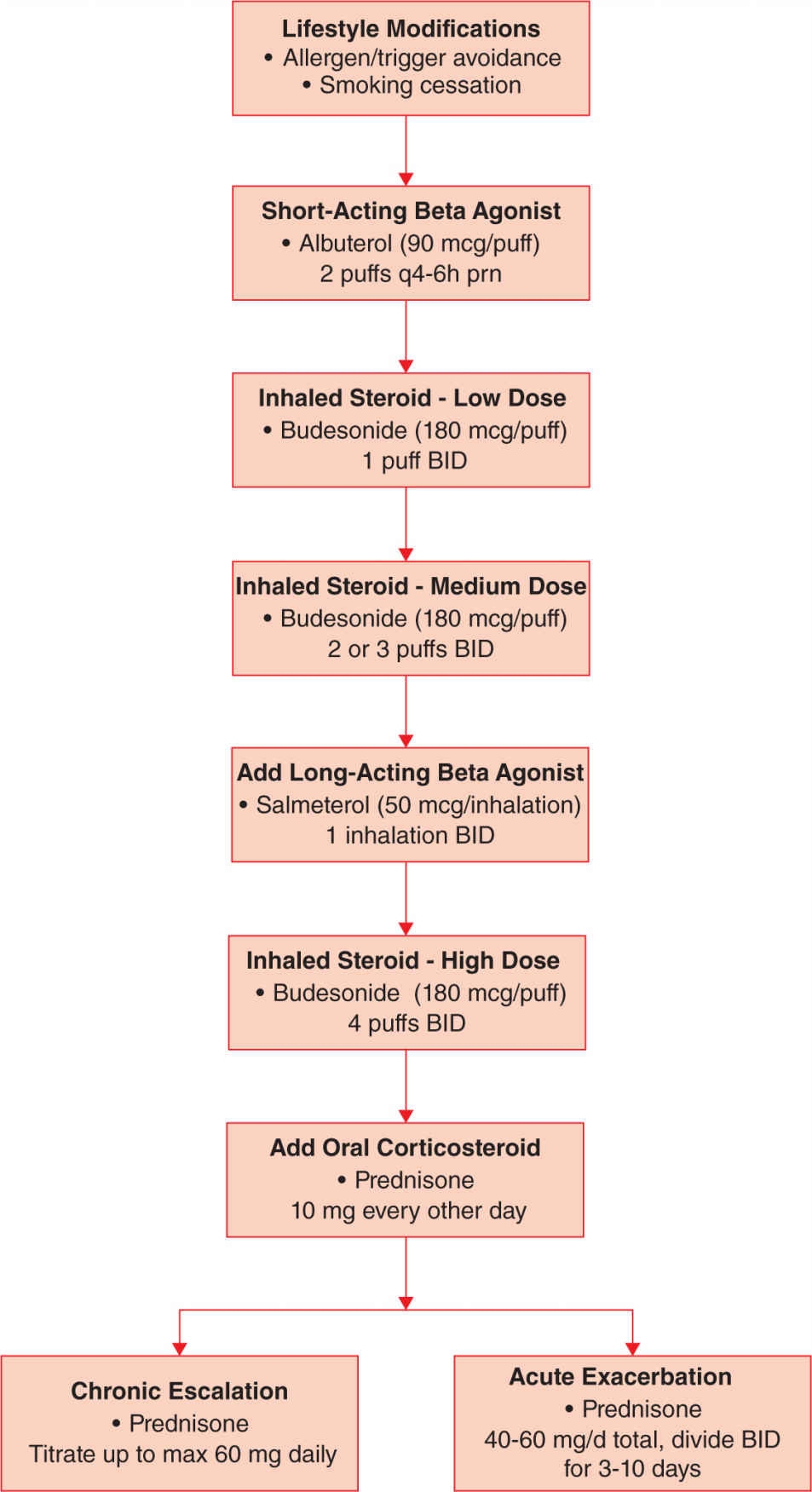

A stepwise approach to pharmacologic treatment in asthma is recommended. Patients should be counseled that it is safer to be treated with medications to control asthma during pregnancy than it is to avoid medications and have symptoms and exacerbations.4,6 No asthma medications have received a pregnancy category A safety profile, but it has been found that well-controlled asthma improves outcomes as compared with untreated asthma. One simplified outpatient management algorithm for escalating medications is presented in Figure 10-2. Patients who are maintained on allergen immunotherapy may continue, but it is not recommended to begin allergy injections while pregnant because of the risk of anaphylaxis.4,6

Intermittent Asthma

No daily controller medication is needed for patients who meet criteria for intermittent asthma. A rescue inhaler can be prescribed to improve intermittent symptoms as needed. The rescue therapy of choice for pregnant patients is albuterol, a short-acting β2-agonist. The patient can be instructed to use two to four puffs every 20 minutes until symptoms improve or 1 hour has passed. Fetal kick counts should be noted by the patient whenever symptoms increase. A woman should call her physician if her PEF does not improve to 80% of her personal best or if fetal movement is decreased.6

Persistent Asthma

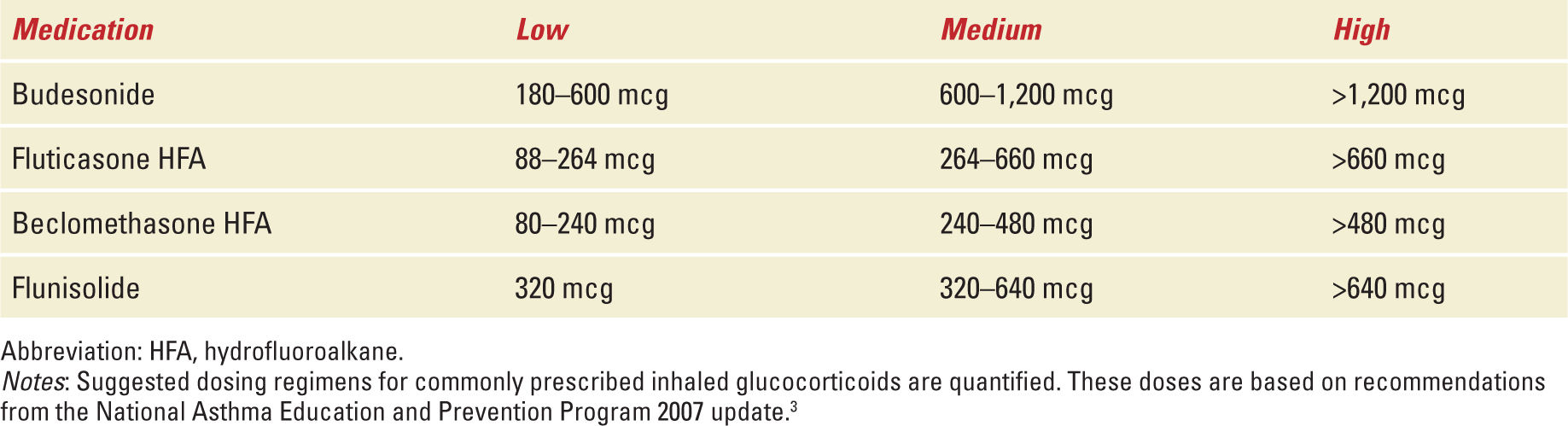

Women with persistent asthma should be maintained on daily controller therapy. First-line controller therapy in pregnancy is low-dose inhaled corticosteroids.6 Inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce exacerbations and improve lung function during pregnancy. The studies have also shown that there is no increase in congenital malformations in babies born to women who have used inhaled corticosteroids during their pregnancy. The majority of the data has been from patients using budesonide and therefore budesonide is the most recommended inhaled corticosteroid for pregnant patients.4 Table 10-3 shows the common doses used of inhaled steroids.

Inhaled Corticosteroid Dosing Regimens |

The most appropriate therapy to add in pregnancy is a long-acting β2-agonist when symptoms are not well controlled with inhaled corticosteroids. The two long-acting β2-agonists available are salmeterol and formoterol. A long-acting β2-agonist can be added to low-dose inhaled corticosteroids or the inhaled corticosteroid dose can be increased to medium dose. Once a long-acting β2-agonist and inhaled corticosteroid at medium dose are both being used, the next step is to escalate to high-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroid is simply done by increasing the number of puffs each day into the dosing range for the chosen medication.6 If the patient is not well controlled on a single inhaled controller medication, combination inhalers may be used. Patients who are not well controlled with the above steps may require scheduled daily oral corticosteroids. These patients should be referred to an asthma specialist to assist in their care.4

Other therapies that can be used, but are not first line, include theophylline, leukotriene receptor antagonists, such as montelukast or zafirlukast, and cromolyn.6 Theophylline has been found to increase side effects and have a narrow therapeutic index.4,6 Studies did show safety of theophylline during pregnancy when kept in the therapeutic range of serum concentration between 5 and 12 μg/mL. Timed release formulations may provide less fluctuation in serum concentration and should be used when theophylline is continued during pregnancy.4 There are minimal data on leukotriene receptor antagonists during pregnancy.4,6 If a patient has been well controlled on a leukotriene receptor antagonist before pregnancy continuing it through pregnancy can be considered.4 Cromolyn is a historically used long-term control medication with an excellent safety profile and tolerance by patients.

Once a patient is meeting criteria for well-controlled asthma, the medications should be maintained at the current dose. Outside of pregnancy, if a patient is well controlled for a number of months, a step down in therapy could be considered. In pregnancy, however, this is typically not recommended given the risk to the mother and fetus of having an exacerbation. Once postpartum, a step down in therapy can be attempted.6

Inpatient

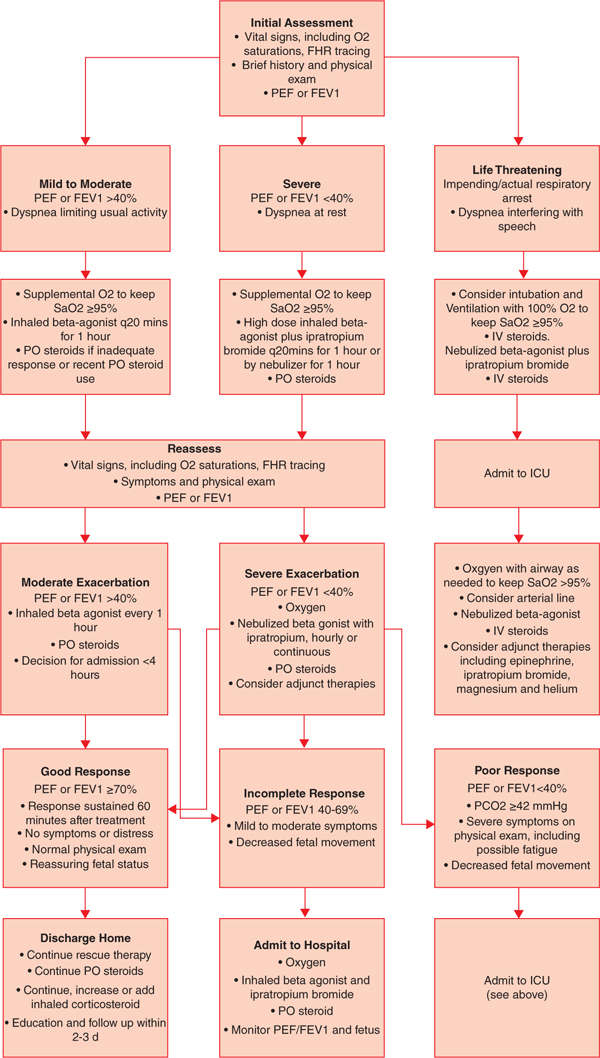

When a patient presents to the hospital with asthma exacerbation, a complete history and physical exam should be performed. Either FEV1 or PEF should be completed to assess pulmonary function. An oxygen saturation reading should always be obtained, and an arterial blood gas can be drawn if the patient shows evidence of respiratory distress.6 Fetal hypoxia has been associated with maternal Pao2 <60 mmHg. Supplemental oxygen should be applied to maintain oxygen saturation ≥95%.4 Noninvasive methods of oxygen delivery include nasal cannulas, oxygen masks, and partial and complete non-rebreathing masks.7 If the fetus is viable, fetal well-being should be monitored by continuous electronic fetal monitoring or assessed with a biophysical profile.6 Intravenous (IV) fluids should be given if the patient is determined to be hypovolemic. A theophylline level should be obtained in patients who are taking theophylline at home.8 A chest X-ray does not need to be routinely obtained but can help evaluate for confounding disorders leading to respiratory distress.4

Treatment for an acute asthma exacerbation should be initiated with an albuterol nebulizer. The patient should be closely evaluated for their response to treatment. Treatments can be given every 20 minutes for the first hour.4 In our institution, respiratory therapists facilitate these treatments. A poor response to albuterol treatment is an indication for inpatient hospitalization. On pulmonary function testing, a poor response would be an FEV1 or PEF less than 50% compared with baseline.6

Oral corticosteroids should be considered in two situations. The patient should be restarted on oral corticosteroids if they have recently taken oral corticosteroids. Oral steroids are equally effective than IV steroids. In addition, if the patient has no response to initial albuterol and the patient is stable, an oral course of oral steroids should be administered. IV corticosteroids should be considered in patients unable to take steroids per mouth (eg, patient with impending respiratory failure).4

Ipratropium bromide is an inhaled anticholinergic agent that can be used in acute asthma exacerbations. It causes parasympathetic blockade that potentiates the effect of β-agonists. It is pregnancy category B but has not shown any benefit as a long-term therapy.8

Discharge from the hospital can be considered for patients who have symptomatically improved, have reassuring fetal monitoring, and have FEV1 or PEF values at least 70% of their personal best for at least an hour after their last treatment. Patients should be instructed to continue following their asthma action plan, using their rescue inhaler as needed. If inhaled corticosteroids were previously taken, they should be continued. Importantly, if the patient was not previously on inhaled corticosteroid therapy, an inhaled corticosteroid should be added to the patient’s regimen upon discharge.4 If oral corticosteroids were needed as a part of the treatment for their acute exacerbation, they should be continued. The recommended dose for prednisone, methylprednisolone, or prednisolone is 40 to 60 mg total daily, in either single dosing or split for twice daily dosing, for 3 to 10 days. The patient should be scheduled for outpatient follow-up within 5 days of discharge. The patient’s controller medications should be escalated as needed until criteria for well controlled is met.6 A flowchart for escalation of outpatient therapy is detailed in Figure 10-3, and an algorithm for acute exacerbation management is shown in Figure 10-4.

FIGURE 10-3. Treatment algorithm. A simplified stepwise approach to the escalation of treatment is shown. Prednisone may be substituted with prednisolone or methylprednisolone using the same dosing guidelines.

FIGURE 10-4. Acute asthma management algorithm. This flow diagram is a guideline for assessment and treatment of acute asthma complaints.3,7 Mild asthma exacerbations are usually cared for at home and have good relief with rescue inhaler use. Occasionally, a mild exacerbation will require the use of a short course of oral corticosteroids. A moderate exacerbation typically requires care in the office or Emergency Department (ED)/triage and will need rescue inhaler and oral corticosteroid treatment. Residual symptoms tend to last a few days after treatment were initiated. Severe exacerbations get little relief from rescue inhaler therapy and typically the patient can demonstrate with accessory muscle use and chest retraction. Severe exacerbations may require oral or IV corticosteroids and may not have resolution of symptoms for more than 3 days after initiation of treatment.3 FHR, fetal heart rate; IV, intravenous; PEF, peak expiratory flow; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; Pco2, partial pressure carbon dioxide; Sao2, oxygen saturation.

Critical Care

A multidisciplinary approach to care is crucial in the critical care settings but is also helpful to be employed in less severe cases. A team of providers including high-risk obstetricians, neonatologists, asthma specialists, and medical intensive care physicians working together will provide the most comprehensive care to the critically ill patient. It is recommended that patients with any signs of respiratory fatigue, including significant tachypnea and accessory muscle use, symptoms of altered mental status, or a Pco2 of greater than 42 mmHg should be monitored in the intensive care unit.6,8

The patient should be treated aggressively with short-acting β2-agonist therapy and IV corticosteroids. Ipratropium bromide can also be given to potentiate the response to β-agonist therapy. Supplemental oxygen should be administered. Acute respiratory failure in pregnancy is rare but can be a consequence of severe maternal asthma. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary. A progressively increasing Paco2 is an indication for intubation and ventilation. The goal of mechanical ventilation is to prevent hypercarbia, respiratory failure, and fetal acidosis. Table 10-4 lists indications for endotracheal intubation in asthma exacerbations. Continuous fetal monitoring should be considered for a viable fetus until the patient is stabilized.8 The ventilator should be set with a low respiratory rate and small tidal volume of 6 to 8 mL/kg (lean body weight) to prevent auto-positive end-expiratory pressure. If necessary, the inspiratory time may be shortened to allow for more time during expiration. Paralysis may be necessary to prevent dyssynchrony between the patient and the ventilator.

Indications for Intubation |