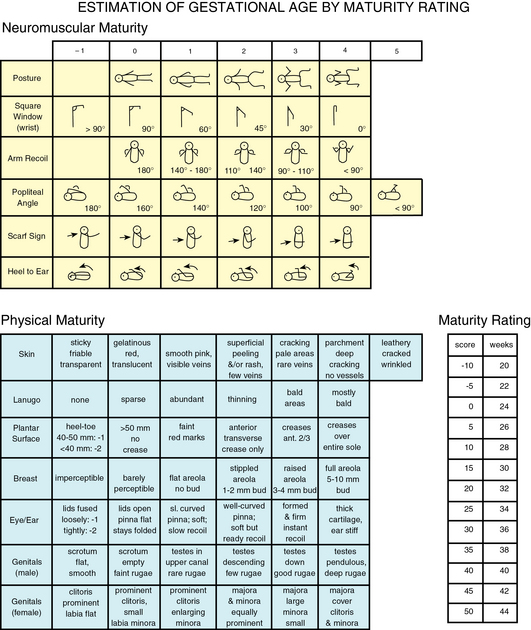

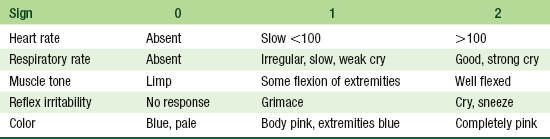

CHAPTER 2 Obtaining an accurate assessment of gestational age begins with the prenatal history and birth history and can assist the health care provider in anticipating conditions associated with preterm birth. The prenatal assessment includes a maternal history of the last menstrual period, history of prenatal care, maternal weight gain and general health during pregnancy, maternal infections, hypertension, history of toxemia or other complications of pregnancy, and history of substance abuse or physical abuse. The birth history includes history of the onset and length of labor and the progression and method of delivery (see Chapter 4). The New Ballard Score (NBS) (Figure 2-1) is the tool most often used to evaluate the gestational age of newborn infants. The NBS is a valid tool and accurately assesses gestational age for extremely low birth weight infants ≤1000 g or extremely premature infants from 20 weeks to term infants from 40 to 44 weeks of gestation.1 The NBS is a revision of the original Dubowitz scale, which was used to determine gestational age of infants 35 to 42 weeks of age. The NBS consists of six physical and six neuromuscular criteria for assessing maturity. The criteria for extremely preterm infants correlates with 1 and 0 on the scale. Gestational age must be determined within 48 hours after birth except in the case of the extremely preterm infant or extremely low birth weight infant whose age should be determined within 12 hours after birth. Assessment of neuromuscular maturity score should be repeated within 48 hours after birth if neonatal asphyxia or maternal anesthesia may have affected initial assessments (Box 2-1). FIGURE 2-1 New Ballard Score. (From Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K et al: New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants, J Pediatr 119(3):418, 1991.) The Apgar scoring system (Table 2-1) reflects the transition of the neonate to extrauterine life. The Apgar assessment performed at 1 minute and again at 5 minutes after birth reflects the heart rate, observation of respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color of the newborn (Table 2-2). The Apgar score is not predictive of long-term perinatal outcomes or neurological status, but remains the standard for assessing viability of the newborn immediately after birth. The Physiscore is a physiological assessment score for preterm infants based on electronic non-invasive measurements monitored in the first 3 hours of life. It may provide higher accuracy of morbidity than the Apgar score.2 TABLE 2-1 Data from Apgar V: Evaluation of the newborn infant, second report, JAMA 168(15):1985-1988, 1958. TABLE 2-2 Interpretation of Apgar Scores Term infants are born between the 38th and 41st weeks of gestation and normally lose about 5% to 10% of their birth weight in the first 72 hours after birth. The average weight loss is 5% to 7% over 3 to 4 days. Postterm infants are born at 42 weeks of gestation and represent about 10% of the newborn population. Postterm infants have an increased incidence of fetal distress and perinatal asphyxia, often due to increased weight gain before delivery. In term infants, a weight loss of >10% may indicate a poor feeding pattern or a more serious postnatal condition and requires thorough investigation and close follow-up. For the infant who is breastfed, observation of feeding and latch to the nipple is particularly important for the breastfed infant with a >7% to >10% weight loss. By 2 weeks of age, term infants have normally regained their birth weight. An infant is considered preterm when born before the end of the 37th week. The weight and gestational age of the infant together predict the relative risk of mortality. During the first year of life, premature infants tend to grow more slowly than term infants even when using the growth curve standard for corrected age (see Appendix A). Health care providers should use the adjusted age standard when plotting the growth of the preterm infant until the infant is 2½ years old. At this point, the difference is no longer statistically significant. Low birth weight (LBW) infants are those infants born weighing <2500 g. Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants are those infants who weigh <1500 g at birth, and infants weighing ≤1000 g are considered extremely low birth weight (ELBW). There has been an increase in the number of VLBW infants due mainly to the increase in prematurely born multiple gestations. However, race and ethnicity, maternal age, maternal health and nutrition, substance abuse during pregnancy, environmental toxins, and access to prenatal care all contribute to the risk of LBW infants. In 2010, the prevalence of LBW infants in the United States was 8.2%, with the highest prevalence among African-Americans.4 Box 2-2 presents maternal risk factors for LBW and VLBW infants. Infants weighing <2500 g at birth or infants with weight below the 10th percentile for age are considered small for gestational age (SGA). The head may be microcephalic, or small in proportion to the body, and head circumference may be below the 5th percentile for age. With adequate nutrition, SGA infants experience overall catch-up growth. Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) may contribute to the reduction in growth in SGA infants, but maternal, fetal, and placental factors all affect pregnancy outcomes. Head circumference is normally the first growth parameter to show catch-up growth, followed by weight, and then length. Fifty percent of SGA infants remain below average weight at 3 years of age.5 The mortality rate for the SGA infant is almost five times that of term infants.6 Large for gestational age (LGA) is defined as birth weight >2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean for gestational age or weight above the 90th percentile for age. The increased weight may result from fetal factors, which include genetic and chromosomal disorders, or from maternal factors, such as obesity or diabetes. Maternal hyperglycemia exposes the fetus to increased levels of glucose, which increases fetal insulin secretion.5 Increased insulin levels increase fat deposits in the fetus and often result in LGA infants. Diabetic mothers who are insulin-dependent and in poor control during the early trimesters of pregnancy have characteristically large infants. LGA infants are at risk for birth trauma, neonatal asphyxia, hypoglycemia, polycythemia, and hyperbilirubinemia. Growth is the most dynamic aspect of childhood. In the early years, the measurements of height and weight are key indicators of health. Abnormal progression of growth and maturation is often the first indicator to the health care provider of abnormalities in the growth pattern. Normal growth proceeds in a predictable pattern during childhood from cephalocaudal (head to tail) and from proximodistal (near to far). Plotting serial measurements regularly on a standardized growth curve for age and gender is a reliable method of monitoring growth and is an essential component of comprehensive well-child care (see Appendix A). Accurate assessment of growth begins in the newborn period by evaluating progress on the growth curve and continues throughout childhood and adolescence by evaluating growth in relation to age (see the inside back cover). Using the correct technique when gathering measurements is one of the significant challenges in pediatrics. Measurement of head circumference is a routine part of growth assessment in the first 2 years of life. Accurate measurement of the head is taken with the measuring tape around the head placed at the point of greatest circumference from the occipital protuberance above the base of the skull to the midforehead or point of greatest bossing of the frontal bone (Figure 2-2). The head circumference measurement is then plotted on the growth curve specific for sex and age at each well-child visit to determine if the growth pattern is normal. If the initial head measurement is plotted on the growth chart and indicates a concerning pattern of growth, it is important to remeasure the head to ensure accuracy of head size. A head circumference that plots 1 to 2 SD above height and weight on the growth curve or >95th percentile or <5th percentile for age should be evaluated. Microcephaly may be indicative of an SGA infant, IUGR, or premature closure of the cranial sutures, termed craniosynostosis, which requires immediate referral. Macrocephaly, a large head in proportion to the body, may indicate increased intracranial pressure or may be a familial variant. Consistent and accurate assessment of the head circumference is a critical part of the assessment of normal growth and development. Height is the most stable measurement of growth and maturation in childhood. Linear growth is genetically predetermined, and therefore adult height generally occurs within a predictable range if accurate family history is available. Linear growth often occurs in spurts followed by long quiescent periods in which no growth occurs. Infants and young children may demonstrate an increase in appetite before a growth spurt, followed by an increased need for sleep. For the infant or toddler, recumbent height is required for accurate measurement of linear growth. Place the infant supine on a flat surface or examination table equipped with a measuring device. Accurate measurement requires the infant’s legs to be flat against the examination table and the foot in the level position. Term newborns vary in height between 18 and 22 inches (45 to 55 cm) at birth, and height increases by approximately 1 inch per month over the first few months of life. Although less accurate than the measuring device, infant measurement can be taken on the examination table by marking the position of the top of the head and the bottom of the foot on table paper and then determining length with a measuring tape. Term infants generally increase in length by 50% in the first year. The increase is primarily in truncal growth. Doubling the height at 2 years of age can give an estimate of adult height. Obese children are taller than children of average weight, often 1 SD above their counterparts for age (Box 2-3).

Assessment parameters

Gestational age in the newborn

Total Score

Assessment

0-2

Severe asphyxia

3-4

Moderate asphyxia

5-7

Mild asphyxia

8-10

No asphyxia

Term infants

Preterm infants

Low birth weight infants

Small for gestational age

Large for gestational age

Normal growth

Measurement

Head circumference

Height