Chapter 260 Arboviral Encephalitis outside North America

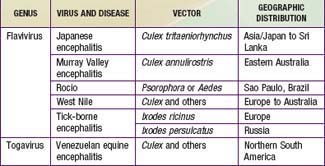

The principal causes of arboviral encephalitis outside North America are Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus, Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), and West Nile (WN) virus (Table 260-1).

260.1 Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for VEE. The treatment is intensive supportive care (Chapter 62), including control of seizures (Chapter 586).

Gubler DJ. The continuing spread of West Nile virus in the western hemisphere. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1039-1046.

Kramer LD, Styer LM, Ebel GD. A global perspective on the epidemiology of West Nile virus. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:61-81.

Siegel-Itzkovich J. Twelve die of West Nile virus in Israel. Br Med J. 2000;321:724.

Tsai TF, Popovici F, Cerescu C, et al. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet. 1998;352:767-771.