Apparent Life-Threatening Events

Gerald M. Loughlin

John L. Carroll

An apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) describes a complex of observations and events that are perceived by the child’s caregiver to be life-threatening (Table 117A.1). In 1986, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference defined ALTE as “an episode that is frightening to the observer and that is characterized by some combination of apnea (central or occasionally obstructive), color change (usually cyanotic or pallid, but occasionally erythematous or plethoric), marked change in muscle tone (usually marked limpness), choking, or gagging. In some cases, the observer fears that the infant has died.”

Older descriptive terms for this condition [aborted sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), near-miss SIDS] are a source of confusion and should not be used; the persistence of such terms reflects a misunderstanding of the epidemiology and prognostic implications of an ALTE. Two observations serve to illustrate this point. Because an ALTE must, by definition, be observed, any cause of death that was truly quiet, such as a sudden cardiac arrhythmia, would be less likely to appear as an ALTE and more likely to result in quiet unexpected death. Likewise, because observation is required, an ALTE is most likely to be observed and reported when the parent or caretaker is awake, which biases the reporting of events to times when the parent is more likely to be awake. Because it is impossible to ascertain whether an episode was actually life-threatening, the incidence of ALTE is unknown or, at best, crudely estimated. In New Zealand, the average annual hospital admission rate for ALTE was reported to be 9.4 in 1,000 live births, which probably underestimates the incidence, because it excludes milder cases not admitted to the hospital.

TABLE 117A.1. HISTORY OF INFANTS WITH UNEXPLAINED APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whatever the cause, the pediatrician faced with one of these infants is presented with a frustrating management problem. Despite the absence of definitive information on the etiology and exact nature of the event, evaluation and therapeutic decisions must be made. This chapter focuses on how these children should be evaluated and treated.

ETIOLOGY

ALTE is not a diagnosis. The term merely describes a common manner of presentation for many different disorders (Table 117A.2). In most studies of ALTE, a possible or likely cause of the event is discovered in approximately half of cases. The occurrence of an ALTE often reflects developmental immaturity in cardiorespiratory responses; these infants appear to experience an exaggerated response to commonly occurring stressors in an infant’s life. However, ALTE also may represent signs of sepsis, meningitis, poisoning, and other potentially life-threatening conditions. Thus, anything that can cause the appearance described in the NIH’s definition may be an underlying cause of ALTE.

Previously, an ALTE with no definable etiology was termed apnea of infancy. We find this term confusing, and prefer the designation ALTE of unknown etiology. In both term and

preterm infants, approximately 90% of unexplained ALTEs occur before the infant is 16 weeks old. Although apnea may be one component of an ALTE, central apnea is a normal finding at all ages; not all episodes of apnea, even if abnormal, are life-threatening; and not all ALTEs involve apnea. The role of apnea in the pathophysiology of ALTE is further complicated because some apnea is a component of the normal variability of breathing in nearly all infants. The absence of airflow, termed apnea, may be the result of absence of respiratory effort (central), obstruction of the airway (obstructive), or a combination of both mechanisms (mixed). Occasional short central apnea, typically of less than 20 seconds and usually preceded by a sigh, may be a normal finding at any age. When it is prolonged longer than 20 to 25 seconds, or is accompanied by bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, pallor, hypotonia, or cyanosis, it is termed pathologic apnea and warrants further investigation. Periodic breathing, recognized as alternating periods of apnea and regular breathing, is defined as three or more breathing pauses of more than 3 seconds’ duration, with less than 20 seconds of breathing between pauses. Short-duration episodes of periodic breathing occur normally during infancy. Central apnea events (of less than 20 seconds) often are misinterpreted by anxious parents as being dangerous, thus adding to the dilemma. Physicians caring for infants with an ALTE must be aware that variability in respiratory pattern, and even short central apnea, is common in otherwise perfectly healthy infants.

preterm infants, approximately 90% of unexplained ALTEs occur before the infant is 16 weeks old. Although apnea may be one component of an ALTE, central apnea is a normal finding at all ages; not all episodes of apnea, even if abnormal, are life-threatening; and not all ALTEs involve apnea. The role of apnea in the pathophysiology of ALTE is further complicated because some apnea is a component of the normal variability of breathing in nearly all infants. The absence of airflow, termed apnea, may be the result of absence of respiratory effort (central), obstruction of the airway (obstructive), or a combination of both mechanisms (mixed). Occasional short central apnea, typically of less than 20 seconds and usually preceded by a sigh, may be a normal finding at any age. When it is prolonged longer than 20 to 25 seconds, or is accompanied by bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, pallor, hypotonia, or cyanosis, it is termed pathologic apnea and warrants further investigation. Periodic breathing, recognized as alternating periods of apnea and regular breathing, is defined as three or more breathing pauses of more than 3 seconds’ duration, with less than 20 seconds of breathing between pauses. Short-duration episodes of periodic breathing occur normally during infancy. Central apnea events (of less than 20 seconds) often are misinterpreted by anxious parents as being dangerous, thus adding to the dilemma. Physicians caring for infants with an ALTE must be aware that variability in respiratory pattern, and even short central apnea, is common in otherwise perfectly healthy infants.

TABLE 117A.2. SOME CAUSES OF APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENTS | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

APPROACH TO THE INFANT AFTER AN APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENT

Our lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of SIDS, coupled with our inability to predict who is at risk for a sudden unexplained death, places the physician responsible for infants who experience an ALTE in a difficult position. Unfortunately, the limitations of our knowledge have resulted in confusion and controversy surrounding the management of infants who are perceived as being at risk of sudden death. This discussion focuses on a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of infants with ALTE, based on available data. As new information is added and clinical experience expands, these recommendations will undoubtedly change.

Although the European Society for the Study and Prevention of Infant Death (ESPID) published recommendations for evaluation of infants with ALTE in 2004 (see Suggested Readings), no comprehensive official guidelines exist for the evaluation and management of ALTE in the United States. General guidelines from U.S. sources may be pieced together from general statements in Consensus Conference Statement from the 1986 NIH Consensus Conference on Infantile Apnea and Home Monitoring and the 2003 Policy Statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics on Apnea, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, and Home Monitoring (see Suggested Readings).

The first steps in evaluating these patients should focus both on ruling out treatable causes of life-threatening events and on determining if a life-threatening or dangerous event actually occurred. In many instances, parents have witnessed a normal physiologic variation that appears to be life-threatening to the inexperienced layperson. Normal infants can experience respiratory pauses lasting for up to 20 seconds during sleep. Many of these are not associated with color change or desaturation, and frequently they are preceded by a sigh. To a parent waiting for a baby to start breathing again, however, even 10 seconds can seem like an eternity. Thus, this infant may be brought to medical attention in an urgent fashion and labeled as abnormal. The physician is confronted by an anxious parent or caretaker who believes that he has witnessed an event that has endangered the child’s life. Somehow, the physician caring for this child must identify the infant at true risk.

A detailed history of the event is essential. Table 117A.3 summarizes the important features of this history. A description of the circumstances preceding the event is key. Was the patient awake or asleep? Events that occur when the child is awake are often found to be secondary to gastroesophageal reflux or a seizure. Was the event associated with body movements or unusual posturing? Again, this suggests a seizure disorder or gastroesophageal reflux. Was the child struggling to breathe (suggestive of airway obstruction), or were respiratory efforts absent?

An accurate description of the intervention required to reestablish normal breathing is important, because the need for vigorous resuscitation appears to correlate with increased risk of recurrent severe spells and even death. Recovery spontaneously or with minimal intervention (i.e., touching the infant) is reassuring and may suggest that what was witnessed was most likely a normal physiologic event. Information about the time required to reverse the event and the infant’s mental and physical status after the event also is important in planning subsequent evaluation and therapy.

Was the infant premature? Was the delivery difficult? Was respiration initiated in normal fashion at birth? Was there evidence of prior respiratory difficulties? Has the child’s growth and development been appropriate? These questions help to establish a predisposition to abnormalities in control of respiration and also help to identify a chronic condition.

A history of how the infant handles feeding is important. Dysfunctional swallowing is more common in preterm infants and can trigger reflex apnea and bradycardia by direct aspiration, stimulation of laryngeal chemoreceptors, or by reflux of formula into the nasopharynx. Apnea may be central or obstructive, and often occurs during feeding in preterm infants. However, if reflux occurs, apnea may occur at varying intervals after feeding.

Is there a family history of sudden unexplained death in other siblings or relatives? Multiple deaths in a family should make one suspicious about the potential for child abuse or an inherited metabolic disorder. Is there a family history of snoring or obstructive sleep apnea? This information suggests a possible familial predisposition to respiratory control disorders. Table 117A.3 highlights the essential components of the physical examination. An assessment of growth and development, along with a focus on cardiac, neurologic, and respiratory systems, is necessary to identify the subtle signs of chronic conditions that may predispose to life-threatening events. Similarly, evidence of an acute infection (sepsis, central nervous system, respiratory) should be sought so that appropriate therapy can be initiated.

TABLE 117A.3. APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENTS DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Laboratory Studies

A comprehensive laboratory evaluation should be reserved for those infants whose history and physical examination suggest that a significant event took place. This can be a challenge, because the observer’s report often does not help the physician to make these decisions. When the infant is brought to medical attention, a measure of acid–base status and either an arterial blood gas or a measurement of serum bicarbonate and a measurement of blood glucose (if the child has not eaten in several hours), should be obtained as soon as possible. Obviously, the longer the interval between the event and obtaining the sample lessens the value of the data, but it is still worth doing. A serum bicarbonate level is a particularly useful test. A low value suggests that the event may have been severe enough to result in a metabolic acidosis, or may suggest the presence of an underlying metabolic disorder. On the other hand, an elevation of serum bicarbonate is consistent with chronic compensation for respiratory acidosis. Hypoglycemia may indicate an underlying metabolic disorder, such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency as the cause of the ALTE. A complete blood count with differential, looking for anemia, polycythemia, and signs of acute infection, also should be a part of this initial screening approach. An elevated hematocrit suggests underlying chronic hypoxemia. On the other hand, low hematocrit values have been associated with apnea in the preterm infant. The white blood cell count is a window on infection. Long QTc syndromes and other rhythm disturbances may be detected by electrocardiogram.

TABLE 117A.4. OTHER STUDIES POSSIBLY INDICATED IN CHILDREN WITH APPARENT LIFE-THREATENING EVENTS | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Based on results of the initial screening tests, the history and physical examination, or subsequent observations, other studies may be indicated (Table 117A.4). These tests are not necessary for all infants with ALTEs, however, because their yield without specific indications is generally low. For example, events temporarily related to feedings or associated with choking and obstructive breathing, particularly when the infant is awake, require a study of both swallowing and esophageal function. Apnea with feeding is best evaluated with a videofluorographic swallowing study (VFSS) using barium of various consistencies. Esophageal pH monitoring to document abnormal gastroesophageal reflux, or an association between a reflux episode and clinical symptoms, may be helpful in defining a potential relationship. If an initial workup result is negative, and the infant is stable, additional testing can be deferred pending the child’s subsequent clinical course.

Assessment of Cardiorespiratory Patterns

Stimulated by the hypothesis that some aberration of cardiorespiratory control is involved in a significant number of ALTEs, attempts have been made to record heart rate and respiratory rate over extended periods in these infants, to identify underlying abnormalities in cardiorespiratory control that may identify a cause or predict recurrences.

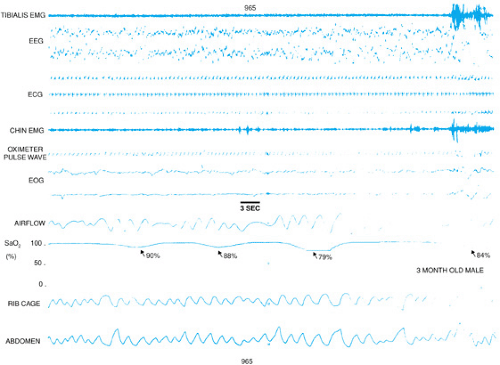

FIGURE 117A.1. A polysomnography tracing from a 3-month-old infant with a history of recurrent spells (see Table 117A.5 for a description of the parameters measured). Note the dramatic decreases in oxygen saturation associated with brief (3-second) apnea.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|