14.6 An approach to chronic cough and cystic fibrosis

Pathophysiology

Issues to keep in mind when the presenting symptom is cough:

• Cough usually resolves spontaneously (called the period effect), which makes evaluation of therapeutic interventions difficult.

• Many cough treatments are not based on the results of randomized controlled trials.

• As the aetiology and management of cough in childhood are quite different to that in adults, extrapolation of the adult cough literature to children can be harmful.

Approach to diagnosis and management

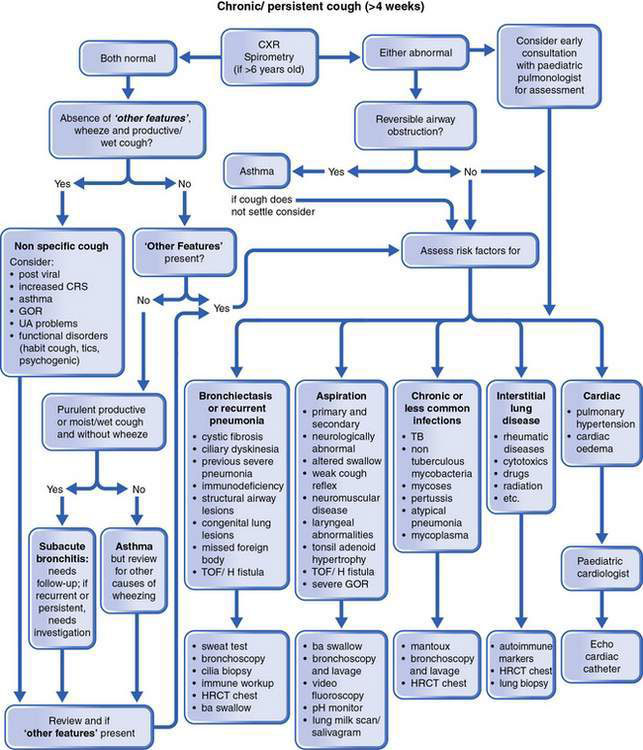

Figure 14.6.1 outlines a schematic approach to the diagnosis and management of chronic cough. The key questions are presented in Box 14.6.1. Initial categorization of cough into acute, subacute and chronic cough according to duration is helpful. There is, however, no strict definition of chronic cough. Most acute cough arises from respiratory viruses and settles within 2 weeks. Subacute cough commonly lasts from 2 to 4 weeks, whereas chronic cough can be defined as cough lasting longer than 4 weeks.

Adrienne, a 13-year-old girl, was referred to a respiratory physician for a chronic cough. She had been managed incorrectly as an asthmatic for more than 10 years. On specific questioning, Adrienne said she had been coughing for as long as she could remember and indicated that her cough was worse in the mornings and that she often expectorated sputum. Her cough had been stable and she had not noticed any exertional dyspnoea. She had no growth failure and did not have digital clubbing. Given that she had some features of bronchiectasis, high-resolution computed tomography of her chest was performed and revealed focal changes in the right basal segment (Fig. 14.6.2). Her serum immunoglobulin levels were normal and she was Mantoux and sweat test negative. On flexible bronchoscopy, a retained foreign body (piece of shell) was visualized and removed from the right medial segment of her right lower lobe. The foreign body had caused prolonged partial bronchial obstruction and was the cause of Adrienne’s localized bronchiectasis.

It is important to define the aetiology of any child’s chronic cough. This child had features listed in Box 14.6.1 that indicate ‘specific cough’ and further investigations were indicated. For children, it is best for investigations to be performed in a children’s facility.

A key point in the assessment of chronic cough is whether it is specific or non-specific, according to the presence or absence of particular features (Box 14.6.2). Children aged less than 6 years do not generally expectorate sputum. Thus the productive cough of older children and adults manifests as a moist or ‘rattly’ cough in younger children. The presence of any of these symptoms or signs raises the possibility of an underlying disorder. Certain cough characteristics are associated with particular illness types (see Table 14.6.1).

Box 14.6.2 Symptoms and signs alerting to the presence of an underlying disorder

Table 14.6.1 Classical recognizable cough in children

| Cough characteristic | Associated illness type |

|---|---|

| Barking or brassy cough | Croup, tracheomalacia, habit cough |

| Honking | Psychogenic |

| Paroxysmal (with/without whoop) | Pertussis and paratussis |

| Staccato | Chlamydia in infants |

| Cough productive of casts | Plastic bronchitis |

Cough, asthma and allergy

Gino was first seen by a paediatric respiratory physician when aged 8 years. He had been receiving 2000 μg/day inhaled corticosteroids for the last 6 years for a chronic dry cough; he had been managed as an ‘asthmatic’ and his medications were escalated when his cough did not respond to the steroids. When seen, his chest X-ray findings and spirometry were normal, and he was cushingoid (Fig. 14.6.3). Earlier pictures of him showed a normal-sized 3-year-old boy and his 6-year-old brother’s body habitus was normal. Gino had been exposed to tobacco smoke and had an element of habitual cough. His asthma medications were subsequently withdrawn and his cough eventually subsided when he was no longer exposed to tobacco smoke and received appropriate counselling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree