4 Allergy and Immunology

Immunologic Hypersensitivity Disorders

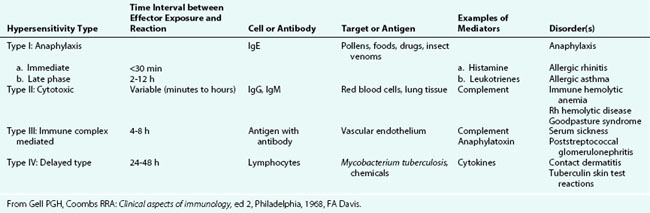

Hypersensitivity disorders of the human immune system have been classified by Gell and Coombs into four groups (Table 4-1). Type I reactions occur promptly after the sensitized individual is exposed to an antigen and are mediated by specific IgE antibody. Cross-linking of IgE on the surface of mast cells and basophils leads to release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators. This mechanism is responsible for the common disorders of immediate hypersensitivity, such as allergic rhinitis and urticaria. So-called “anaphylactoid” reactions are clinically similar, but are caused by degranulation of mast cells and basophils in the absence of specific IgE. Type II reactions involve antibodies directed against antigenic components of peripheral blood or tissue cells or foreign antigens, resulting in cell destruction. Examples of this type include autoimmune hemolytic anemia and Rh and ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn. In type III reactions, antigen–antibody complexes form and are deposited in the lining of blood vessels, stimulating tissue inflammation mediated by complement or activated white blood cells. Examples of this type of reaction are serum sickness and the immune complex–mediated renal diseases. Type IV reactions involve T cell–mediated tissue inflammation and typically occur 24 to 48 hours after exposure. Examples of this type are tuberculin (purified protein derivative, PPD) reactions and contact dermatitis (see Chapter 8).

Type I Disorders

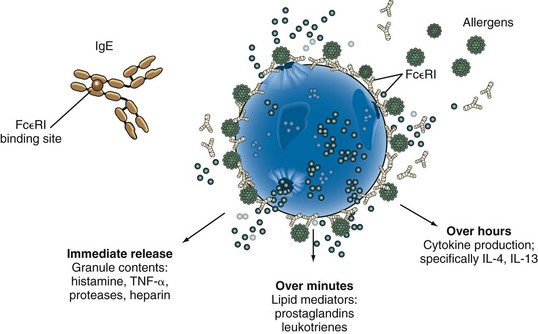

The development of type I hypersensitivity depends on hereditary predisposition, sensitization by exposure to an antigen, and subsequent reexposure to the antigen leading to an allergic reaction. Antigens that stimulate allergic reactions are known as allergens, and the mechanism of allergen-induced mediator release in type I hypersensitivity reactions is shown in Figure 4-1. IgE antibodies directed toward specific allergens are bound to the high-affinity IgE receptor on mast cells and basophils. When allergen causes cross-linking of IgE antibodies on the cell surface, the cell becomes activated, leading to the release of preformed mediators and the generation of the early and late mediators of anaphylaxis. The preformed mediators include histamine, tryptase, chymase, heparin, and other proteases that drive the earliest symptoms of anaphylaxis. A serum tryptase level is currently the best biologic marker of anaphylaxis, but it is still a relatively insensitive test. Serum tryptase levels should be obtained close to the onset of anaphylaxis because levels peak in 1 hour and remain elevated for only 4 to 24 hours. The early and late mediators generated by mast cell activation include prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and cytokines. These mediators, which are generated over minutes to hours, continue to drive the clinical symptoms of the allergic reaction and initiate an inflammatory cascade that leads to the recruitment of eosinophils, basophils, and lymphocytes.

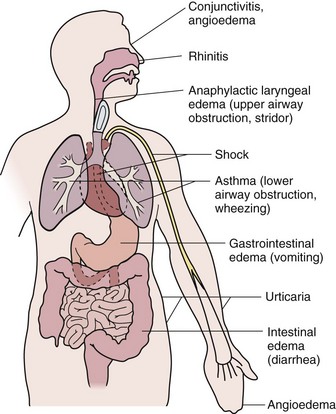

Type I reactions may occur in one or more target organs including the upper and lower respiratory tracts, cardiovascular system, skin, conjunctivae, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Manifestations depend on the systems involved, as shown in Figure 4-2. The most common manifestation of type I reaction is seasonal allergic rhinitis with a prevalence of at least 25%. The most serious manifestation of type I hypersensitivity is anaphylaxis, which can simultaneously involve all of the organ systems mentioned above.

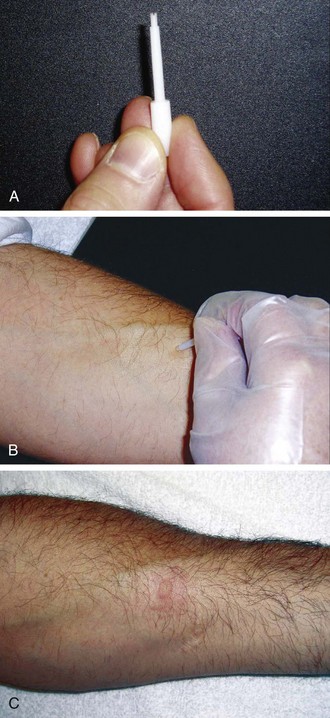

Type I hypersensitivity has been diagnosed by skin testing for more than 100 years. The percutaneous skin test, also known as either the scratch or prick test, is an in vivo method to detect the presence of IgE antibody to specific allergens. The skin prick test is the safest and most specific test and correlates best with symptoms. The skin prick test is typically performed with a plastic lancet on either the forearm or upper back and involves a superficial disruption of the epidermis that is nearly painless (Fig. 4-3). The test leaves a barely visible mark, and when performed properly, the prick site should not bleed. The test is interpreted after 15 to 20 minutes by measuring the maximal diameter of both the wheal and the flare. Skin test results are compared with a negative control, which is usually saline, and a positive control, which is typically histamine. Historically, intradermal tests have been considered to be more sensitive than prick tests, but the specificity is poor and these tests should be used only when ruling out allergic disease is essential.

Allergy skin testing is contraindicated in four clinical situations: (1) when antihistamines have been used in the recent past—this will typically manifest as a negative histamine control; (2) when skin disease limits the area available for testing; (3) during either an asthma exacerbation or episode of anaphylaxis; and (4) when a patient is taking a β-blocking medicine, because these can interfere with epinephrine treatment in rare cases of test-induced anaphylaxis. When skin testing is not possible, in vitro testing is a good alternative. The in vitro tests can be accomplished with just a few milliliters of serum and also may be advantageous for some patients who have a difficult time sitting through allergy tests. In vitro allergy tests are more expensive and less sensitive than allergy prick tests (Table 4-2). In vitro tests are especially helpful in the evaluation of patients with possible food allergies; this is discussed further below.

Table 4-2 Skin Testing Versus In Vitro Testing

| Variable | Skin Test | In Vitro |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of allergic reaction | Rare | No |

| Sensitivity | Very good | Good* |

| Affected by antihistamines | Yes | No |

| Affected by corticosteroids | Not usually | No |

| Affected by extensive dermatitis or dermatographism | Yes | No |

| Broad selection of antigens | Yes | Yes |

| Immediate results | Yes | No |

| Discomfort | Mild | Moderate |

Systemic Anaphylaxis

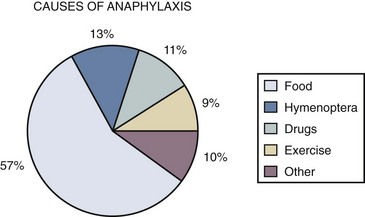

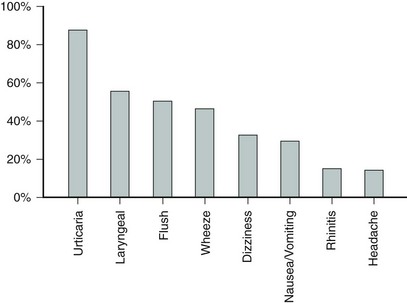

Anaphylaxis results from widespread degranulation of mast cells after cross-linking of IgE on the mast cell surface. A clinically similar reaction in which mast cells degranulate without cross-linking of antigen-specific IgE is termed anaphylactoid. Anaphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis, and a report issued jointly by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network established criteria to define likely anaphylactic episodes (Table 4-3). Onset of anaphylaxis is typically rapid and often explosive after bee stings, drug administration, or food ingestion (Fig. 4-4). The pattern of organ system involvement can vary, based on the antigen, dose, and route of exposure, and can range from isolated urticaria to cardiovascular collapse (Fig. 4-5). Airway obstruction and hypotension are the most severe manifestations of anaphylaxis. The upper or lower airway, or both, can be affected. Upper airway obstruction is due to laryngeal edema, whereas lower airway involvement is due to edema and bronchospasm. Hypotension is caused by vasodilation, which may be complicated by loss of intravascular volume. Vascular collapse may be aggravated by decreases in myocardial function. In addition to the airway and cardiovascular system, other organ systems are also involved in anaphylaxis. The skin is the most commonly involved organ, with urticaria being nearly universal and angioedema often present. GI involvement can manifest as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain due to gut edema.

Table 4-3 Criteria to Define Likely Anaphylactic Episodes

BP, blood pressure; PEF, peak expiratory flow.

* Low systolic blood pressure for children is defined as less than 70 mm Hg from 1 month to 1 year, less than (70 mm Hg + [2 × age in yr]) from 1 to 10 years, and less than 90 mm Hg from 11 to 17 years.

Figure 4-4 Relative frequency of causes of anaphylaxis in children.

(From Novembre E, Cianteroni A, Bernardini R, et al: Anaphylaxis in children: clinical and allergological features, Pediatrics 101:E8, 1998.)

Figure 4-5 Relative frequency of symptoms associated with anaphylaxis.

(Modified from Lieberman P: Anaphylaxis: how to quickly narrow the differential diagnosis, J Respir Dis 20:221-232, 1999.)

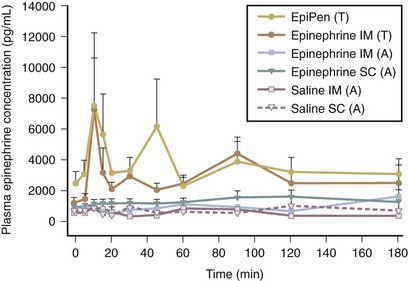

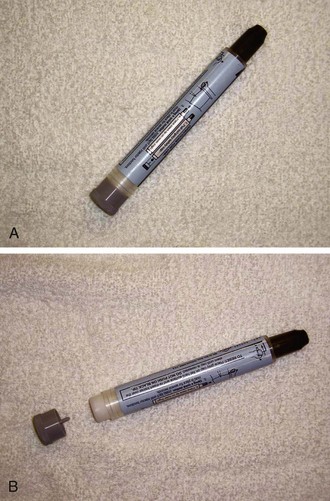

For all reactions but isolated skin symptoms, intramuscular epinephrine is the therapy of choice. Studies have demonstrated the superiority of intramuscular injections compared with subcutaneous injections of epinephrine (Fig. 4-6). Patients at risk should carry self-injectable epinephrine and be trained in its use. There are currently four different epinephrine autoinjector devices: EpiPen, Adrenaclick, Twinject, and a generic autoinjector (Fig. 4-7). All come in two doses: either 0.15 mg or 0.3 mg. Operating technique varies somewhat among the devices, so it is important for families to become familiar with their specific device. Epinephrine is most effective when it is used within 30 to 60 minutes of the onset of anaphylaxis, and other medications should not delay prompt delivery of epinephrine, which is often lifesaving. In cases of hypotension, large-volume fluid resuscitation and intravenous epinephrine may be required. Any administration of epinephrine should be followed by a call to 911 and observation in an emergency department. Albuterol inhalation may be useful for lower airway symptoms, and steroids may prevent late-phase reactions. Antihistamines can be used for reactions confined to the skin and as an adjunct to epinephrine in more severe reactions.

Hymenoptera Sensitivity

The Hymenoptera that have been associated with anaphylaxis come from three subfamilies: Apidae (honeybees); Vespidae (yellow jackets, wasps, and white- and yellow-faced hornets); and Formicidae (fire ants). In the United States, yellow jackets are the most common cause of Hymenoptera-induced anaphylaxis. Yellow jackets typically nest in the ground, are scavengers for food, and, consequently, are frequently encountered at picnics and around garbage cans. The yellow jacket is small with tight yellow and black bands. The honeybee is the least aggressive of the Hymenoptera family. Stings from honeybees occur most commonly in beekeepers and after accidental contact. The honeybee’s stinger is barbed and is retained in the skin after stings (Fig. 4-8). If the stinger is visible, it should be quickly flicked away from the skin with a fingernail. The stinger and venom sac should not be removed by pinching between the thumb and forefinger as this process can express additional venom. Wasps and hornets are very territorial and will sting to protect their nests. The fire ant is an increasingly important cause of Hymenoptera-induced anaphylaxis. Fire ants are found in the southeastern United States, but their natural habitat appears to be expanding.

Food Allergy

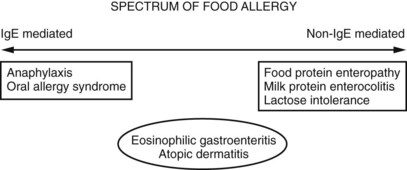

Food allergy can be divided into two broad groups on the basis of the mechanism of disease: (1) type I (IgE-mediated) hypersensitivity and (2) other immunologically mediated reactions (Fig. 4-9). Other food reactions (e.g., lactose intolerance) do not have an immune basis and are referred to as intolerant reactions. Food allergic reactions are highly reproducible (i.e., occur with any exposure to a food), and often are triggered by ingestions of very small quantities. Anaphylaxis is the best described and understood type I hypersensitivity to food. Although contact reactions (erythema, pruritus, hives) are common if an individual touches her or his food allergen, the most severe allergic reactions occur with ingestion. Milk, egg, wheat, soy, and peanut account for more than 90% of food allergic reactions in children. The onset of type I hypersensitivity to milk and egg is almost always in the first year of life. Fortunately, these two foods rarely cause more than generalized urticaria and the sensitivity is eventually outgrown in the vast majority of patients, frequently by school age.

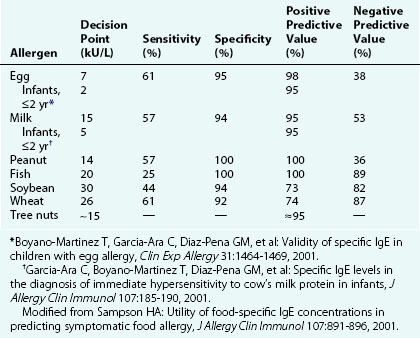

One of the challenges with diagnosing type I hypersensitivity to foods is the poor specificity of both the skin prick and in vitro tests. The “gold standard” for diagnosis of food allergy is a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). A distinction is drawn between patients who are “sensitized,” based on skin or serum testing, and those who are clinically allergic, based on a history of reactions to ingestions. IgE-mediated reactions occur quickly and reproducibly with ingestion of the triggering food. Research using in vitro allergy tests has identified levels of specific IgE against certain foods that predict with 95% certainty a reaction during a DBPCFC. In vitro food-specific IgE levels are most useful clinically when used in association with a patient’s ingestion history and (if indicated) skin test results; in a nationally representative survey study, approximately 17% of the overall population in the United States displayed serum sensitization to either cow’s milk, egg, peanut, or shrimp, and this prevalence rate was even higher (28%) among children ages 1 to 5 years. Yet, on the basis of these serum levels in the same study, only approximately 2.5% of the U.S. population was predicted to be clinically allergic to one of these foods. The data concerning positive predictive levels depend on the age of the patient and are not available for all foods (Table 4-4). The in vitro allergy test may also be repeated over time to try to help with the identification of patients who may have outgrown their sensitivity. The sensitivity of both the skin prick and in vitro tests is excellent, but not 100%. If there is a strong clinical history of a type I reaction to a food, it may be necessary to perform an oral challenge in a medically supervised setting before food hypersensitivity can be fully ruled out.

Drug Reactions

Drugs can also induce type II, III, and IV Gell and Coombs reactions. The classic Gell and Coombs type II reaction is due to IgG antibodies directed against drug bound to cell surfaces, causing either hemolytic anemia or thrombocytopenia. Serum sickness represents a Gell and Coombs type III reaction. Serum sickness usually begins 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure and involves various symptoms including fever, malaise, arthralgias, arthritis, urticaria, and lymphadenopathy. Many patients with serum sickness will develop a characteristic serpiginous, erythematous, or purpuric eruption at the junction of the palmar or plantar and dorsolateral aspects of the hands and feet, respectively (Fig. 4-10). Patients with serum sickness may have reduced levels of complement components C3 and C4 along with the presence of circulating immune complexes. Serum sickness can be treated with antihistamines, and if the patient fails to improve systemic steroids can be used. Symptoms usually resolve within a few weeks. Future avoidance of the drug inciting the reaction is recommended.

Erythema multiforme minor (EM) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) are drug reactions that do not conform to the Gell and Coombs classification scheme. EM can be caused by drugs or infection or be idiopathic. EM lesions typically begin as dusky, red macules or erythematous papules that evolve into target lesions after 24 to 48 hours (see Chapter 8). The diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical appearance and the absence of significant mucosal involvement. The symptoms can persist for a few weeks, and if discomfort is significant, either antihistamines or steroids can be used. Patients with EM do not experience long-term sequelae from their disease. Patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) have skin symptoms similar to those of EM, but also manifest significant mucosal involvement as well as elevated temperature, and constitutional symptoms. Severe disease with extensive skin and mucous membrane involvement may produce long-term complications. Skin findings with SJS evolve from targetoid lesions to vesicles and bullae followed by sloughing of the skin. SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are most likely manifestations of a single disease that exists along a clinical spectrum. Patients with SJS have less than 10% of the body affected by epidermal detachment and those with TEN have more than 30% of the body affected. TEN is almost always drug induced whereas SJS may be induced by either drugs or infection with Mycoplasma or herpes simplex virus. When drug exposure is the inciting cause, the exposure precedes the onset of skin findings by 1 to 3 weeks. There is no universally accepted therapy, with some studies showing a benefit from high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin and other studies showing no benefit. Glucocorticoids are relatively contraindicated in this condition in children because some studies have shown a deleterious effect.

Allergic Rhinitis

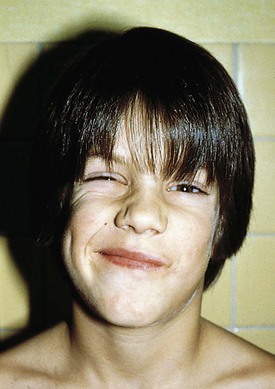

Allergic rhinitis, characterized by inflammation, edema, and weeping of the nasal mucosa, is the most common allergic disorder and occurs in up to 25% of the population. Diagnosis is based on characteristic history, physical findings, and testing for antigen-specific IgE. Common presenting symptoms include nasal congestion and pruritus, clear rhinorrhea, and paroxysms of sneezing. Whereas older children may blow their noses frequently, younger children do not. Instead, they sniff, snort, and repetitively clear their throats. Nasal pruritus stimulates grimacing and twitching (Fig. 4-11) and picking or rubbing of the nose (“allergic salute”). Picking, repetitive sneezing, and blowing along with underlying inflammation may produce enough irritation to cause epistaxis. In the case of allergy to seasonal pollens, the symptoms may be acute, have a sudden onset, and be confined to the period during which the particular airborne pollen is detectable. Seasonal allergic rhinitis tends to be due to trees in the spring, grasses in the summer, and ragweed or other pollens in the fall.

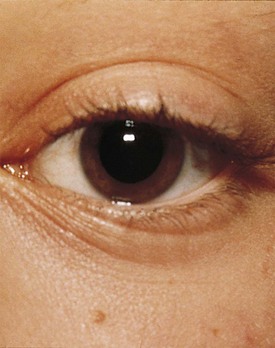

Many children with long-standing allergic rhinitis can be recognized by their facial characteristics. Ocular manifestations of the allergic disposition include cobblestoning of the conjunctivae (see Fig. 4-33), the allergic shiner, and Dennie’s sign. Allergic shiners, that is, bluish discolorations or dark circles beneath the eyes, are commonly observed in patients with allergic rhinitis (Fig. 4-12). This finding represents chronic venous congestion secondary to inflammation. Dennie’s sign refers to prominent folds or creases on the lower eyelid (Fig. 4-13) running parallel to the lower lid margin. Although these lines were originally thought to indicate a predisposition to allergy, data suggest that they may be present in any condition associated with periocular pruritus and scratching or chronic nasal congestion. Frequent upward rubbing of the nose with the palm of the hand (the allergic salute; Fig. 4-14) promotes development of a transverse nasal crease across the lower third of the nose (Fig. 4-15). Chronic obstruction produced by nasal mucosal edema may result in mouth breathing and a typical open-mouthed, adenoid-type facies (Fig. 4-16).

Figure 4-12 Allergic shiners, or dark circles beneath the eyes, in a patient with allergic rhinitis.

On nasal examination, attention should be focused on the position of the nasal septum; nasal patency; mucosal appearance; and presence and character of secretions, polyps, or foreign bodies (see Chapter 23). The typical physical examination findings in allergic rhinitis include a marked decrease in nasal patency resulting from swollen inferior turbinates, which appear pale, edematous, and bluish gray (Fig. 4-17). The mucosa appears edematous, and secretions are clear and watery to mucoid in character.

Children with frequent upper respiratory infections and/or persistent nasal congestion can present a diagnostic challenge. In some cases the phenomenon is due to recurrent viral infections, particularly in children in their first year of day care or nursery school. In other patients, tonsillar and adenoidal hypertrophy provides favorable conditions for recurrent infections (see Chapter 23). Atopic (allergic) children may have increased risk of infection because of impaired flow of secretions due to mucosal edema. Although viral infections tend to produce clear or white discharge in contrast to bacterial infections, which typically produce a purulent yellow or green discharge, there is considerable overlap, limiting the value of this distinction.

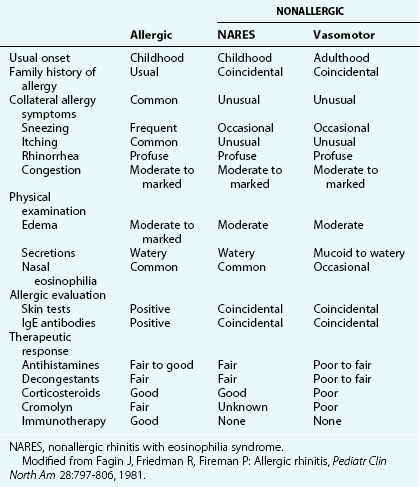

Other forms of rhinitis that must be distinguished from allergic rhinitis are enumerated in Table 4-5. Although characterized by eosinophilia, NARES does not produce nasal pruritus, and patients lack specific IgE antibodies as measured by skin testing or in vitro serum testing. Patients with vasomotor rhinitis do not complain of pruritus, have a clear discharge without eosinophils, and also lack specific IgE antibodies. Vasomotor rhinitis is thus considered a form of noninflammatory rhinitis, the etiology of which is unknown, although it is often triggered by nonspecific stimuli such as cold air exposure or smoke. The condition is diagnosed most frequently in adults but may affect children. Congestion or rhinorrhea may predominate in this disorder. Rhinitis medicamentosa is a condition seen in patients who have been using α-adrenergic vasoconstrictor nose drops (phenylephrine or oxymetazoline) as decongestants for prolonged treatment periods. The disorder is characterized by rebound vasodilation that produces an erythematous, edematous mucosa in association with a profuse clear nasal discharge.

Some children with perennial allergic rhinitis have congestion so constant and severe that it produces signs of chronic nasal obstruction. This must be distinguished from other acquired and congenital causes (see Chapter 23). The history, physical findings, and results of allergy tests for specific IgE and nasal smears, along with therapeutic trials of antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids, will all help lead to a diagnosis.

Respiratory Disease

Asthma

Asthma is the most common chronic respiratory condition affecting children. Defining characteristics of asthma, as elucidated by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (see Bibliography), include the following: (1) lower airway obstruction that is partially or fully reversible either spontaneously or with bronchodilator or antiinflammatory treatments, (2) the presence of lower airway inflammation, and (3) increased lower airway responsiveness (bronchial hyperreactivity). The last is characterized by inherent hyperreactivity of the airways to stimuli including allergens, infection, exercise, chemical agents such as methacholine, cold or dry air, emotions, and weather changes. Many cases of asthma, particularly in children, have an atopic basis. Specific allergens implicated in atopic patients are pollen, mold spores, house dust mites, and animal dander, whereas drugs, food, and insect venoms typically cause similar symptoms of wheezing and respiratory distress as part of anaphylaxis (see earlier discussion). On exposure, these allergens, via cross-linking specific IgE, produce the characteristic features of asthma: mucosal edema, increased mucus production, and smooth muscle contraction that result in airway inflammation, airway hyperreactivity, and bronchoconstriction. These responses combine to produce a state of reversible obstruction of the large and small airways that is the hallmark of asthma.

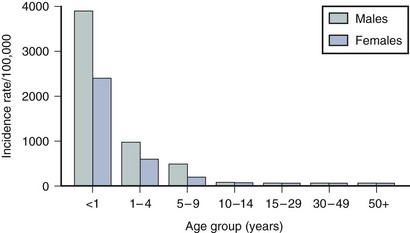

Asthma is one of the leading causes of pediatric morbidity. Indeed, approximately 10% to 12% of children in the United States show signs and symptoms compatible with asthma at some time during childhood. Peak incidence of onset is before the age of 5 years (Fig. 4-18). In childhood, boys are affected more often than girls and tend to have more severe disease. Beyond puberty, the gender distribution is equal because onset in the teenage years is more common in girls, perhaps due to hormonal factors involved in menarche. Asthmatic children with respiratory allergy and eczema usually have more severe courses than those who wheeze only with upper respiratory infections.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree