Do not hyperextend the neck if a cervical spine injury is suspected. Use jaw thrust rather than head tilt.

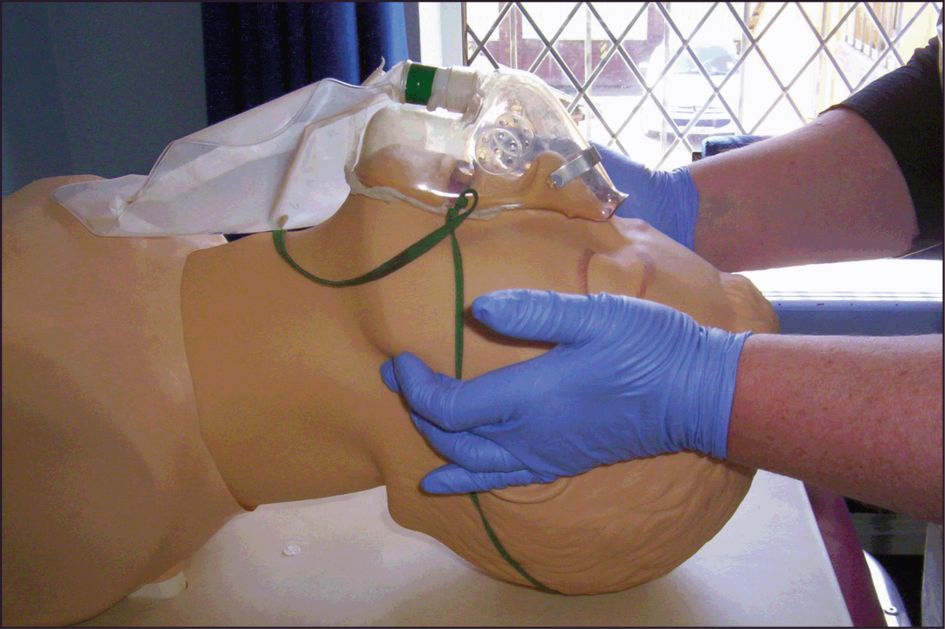

Jaw thrust

Grasp the angles of the mandible, one hand on each side, and move the mandible forward. The jaw thrust is used for the injured patient because it does not destabilise a possible cervical spine fracture and risk converting a fracture without spinal cord injury to one with spinal cord injury. This manoeuvre will open 95% of obstructed upper airways. See Figure 8.2.

Suction

Remove blood and secretions from the oropharynx with a rigid suction device (for example, a Yankauer sucker). A patient with facial or head injuries may have a cribriform plate fracture – in these circumstances suction catheters should not be inserted through the nose, as they could enter the skull and injure the brain.

If attempts to clear the airway do not result in the restoration of spontaneous breathing, this may be because the airway is still not patent or because the airway is patent but there is no breathing. The only way to distinguish these two situations is to put either a pocket mask or facemask over the face and give breaths (either mouth-to-pocket-mask or with selfinflating bag and mask). If the chest rises, this is not an airway problem but a breathing problem. If the chest cannot be made to rise, this is an airway problem.

Clearing the airway may result in improvement in level of consciousness, which then might allow the patient to maintain her own airway.

Maintaining the airway

If the patient cannot maintain her own airway, continue with the jaw thrust or chin lift or try using an oropharyngeal airway.

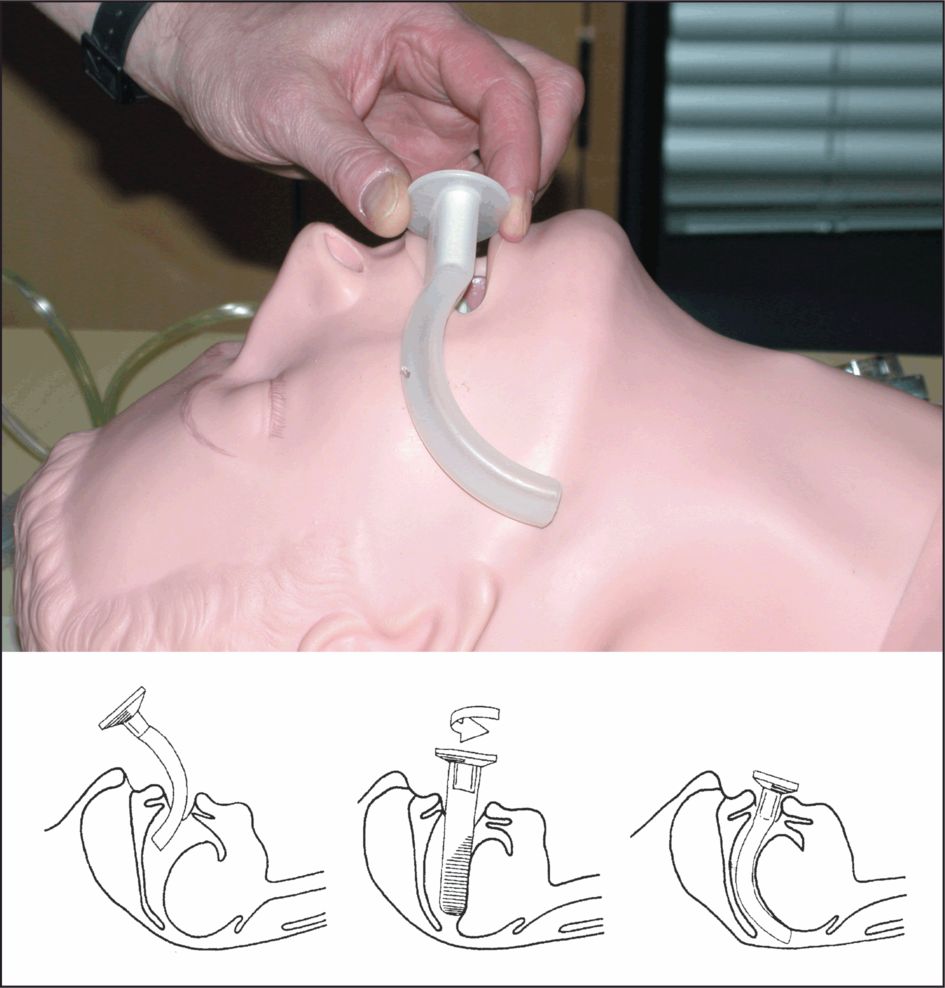

Oropharyngeal airway

The oropharyngeal airway (Guedel type) is inserted into the mouth over the tongue. It stops the tongue falling back and provides a clear passage for airflow. The preferred method is to insert the airway concavity upwards, until the tip reaches the soft palate and then rotate it 180°, slipping it into place over the tongue. Make sure that the oropharyngeal airway does not push the tongue backwards as this will block, rather than open, the patient’s airway. A patient with a gag reflex may not tolerate the oral airway. See Figure 8.3.

Nasopharyngeal airway

A nasopharyngeal airway is better tolerated than the oropharyngeal airway by the more responsive patient. Their use is contraindicated if there is a suspected fractured base of skull. Be aware of the potential for insertion to cause bleeding from the fragile nasal mucosa, which may soil the lungs of a patient with obtunded laryngeal or pharyngeal reflexes (the unconscious or hypotensive patient). This is especially so in pregnancy. Their use is limited to intensive care units where they might be placed by physiotherapists or anaesthetists to facilitate suctioning of pharyngeal secretions. They should only be used if there is an airway problem, an oropharyngeal airway is not being tolerated and an anaesthetist is unavailable.

Be very reluctant to use a nasal airway. They do not have a large part to play in contemporary UK anaesthetic practice because of their potential to cause bleeding, which is exacerbated in pregnancy.

Lubricate the airway and insert it gently through either nostril, straight backwards – not upwards – so that its tip enters the hypopharynx. A safety pin should be applied across the proximal end before insertion to prevent the tube disappearing into the nasal passages. Gentle insertion, good lubrication and using an airway that passes easily into the nose will decrease the incidence of bleeding.

The oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal devices maintain the airway but do not protect it from aspiration.

Advanced airway techniques

Definitive airway is a gold standard for opening, maintaining and protecting the airway. It means that there is a cuffed tube in the trachea attached to oxygen and secured in place. Advanced airway techniques provide a definitive airway.

Advanced airway techniques may be required:

in cases of apnoea

when the above techniques fail

to maintain an airway over the longer term

to protect an airway

to allow accurate control of oxygenation and ventilation

when there is the potential for airway obstruction

to control carbon dioxide levels in the unconscious patient, as a way of minimising the rise in intracranial pressure.

Advanced airway techniques are:

endotracheal intubation

surgical cricothyroidotomy

surgical tracheostomy.

The circumstances and urgency determine the type of advanced airway technique to be used.

Note: The pregnant woman is at increased risk of gastric regurgitation because she has a mechanical obstruction to gastric emptying i.e. the pregnant uterus. She also has reduced tone in the lower oesophageal sphincter as a result of hormonal effects on the smooth muscle. Trauma patients are at increased risk of regurgitation because of reduced gastric emptying. Consequently, the pregnant woman (with or without trauma) without adequate pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes (unconscious or hypotensive) is at increased risk of pulmonary aspiration. The chemical pneumonitis suffered when a pregnant woman aspirates is more severe than in a nonpregnant woman, as the gastric aspirate is more acidic in pregnancy. Consider early definitive airway, particularly in the context of a reduced conscious level.

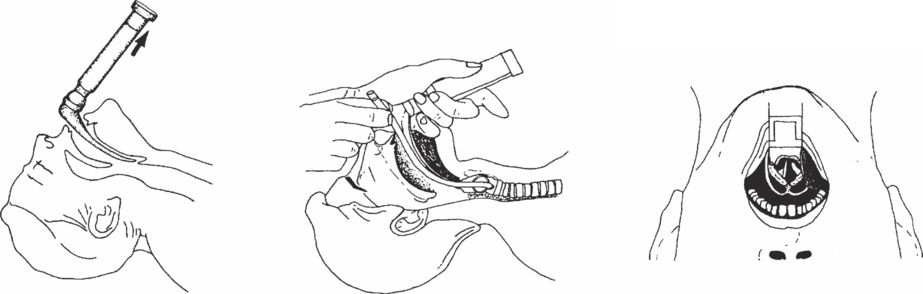

Endotracheal intubation

In a patient with airway or respiratory compromise, the primary aim is to oxygenate the patient and this can initially be successfully achieved by positioning, use of oropharyngeal airways and use of a facemask and self-inflating bag.

If this cannot be achieved, intubation is needed. This should only be carried out without drugs where there is an urgent need for intubation, i.e. in the case of complete airway obstruction or a respiratory arrest, where the airway cannot be otherwise maintained.

It should be emphasised that heavily pregnant women are difficult to intubate and to ventilate with a bag and mask, because of weight gain during pregnancy and the potential for large breasts falling back into the working space. Consequently, for a surgeon or obstetrician, the use of a supraglottic airway device, such as a laryngeal mask (LMA) or a surgical airway may be the preferred option. It is usually easier to maintain an airway or ventilate by bag–valve–mask if the woman is a few degrees head up, rather than lying completely supine. This allows the weight of the breasts and abdomen to fall away from the chest. It may also make intubation easier.

Oral endotracheal intubation is most commonly used. This uses a laryngoscope to visualise the vocal cords. A cuffed endotracheal tube is placed through the vocal cords into the trachea. See Figure 8.4.

Tracheal intubation without using drugs is not possible unless the patient is very deeply unconscious or has sustained a cardiac arrest. If the patient is unconscious, intracranial pathology may be implied and intubation without anaesthetic and muscle-relaxation drugs will cause increases in blood pressure and intracranial pressure, which may exacerbate the intracranial condition. Intubation is therefore always a threat to patient wellbeing unless drugs are used.

Drugs should only be used to intubate by those with adequate anaesthetic training.

Where anaesthetic skills and drugs are available, endotracheal intubation is the preferred method of securing a definitive airway. This technique comprises rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia (‘crash induction’):

preoxygenation

application of cricoid pressure

rapid unconsciousness using drugs

consider gentle bagging, max 20 cm water pressure

rapid placement of endotracheal tube in trachea

inflation of cuff before removal of cricoid pressure

maintenance of cervical spine immobilisation when indicated.

Meticulous care must be taken to keep the cervical spine immobilised if injury to the cervical spine is suspected.

Intermittent oxygenation during difficult intubation

Inability to intubate will not kill. Inability to oxygenate will. If you can oxygenate by bag and mask, this will keep the patient alive.

Avoid prolonged efforts to intubate without intermittently oxygenating and ventilating. Practise taking a deep breath when starting an attempt at intubation. If you have to take a further breath before successfully intubating the patient, abort the attempt and re-oxygenate using the bag and mask technique. The joint guidelines from the DAS and OAA, 2015, suggest a maximum of 2 attempts, with a third only being attempted by an experienced colleague.

The 2006–08 Saving Mothers’ Lives report on maternal deaths in the UK once again identified failure to oxygenate in a patient with a difficult airway as a cause of maternal death.

Correct placement of the endotracheal tube

To check correct placement of the endotracheal tube:

see the endotracheal tube pass between the vocal cords

listen on both sides in the midaxillary line for equal breath sounds

listen over the stomach for gurgling sounds during assisted ventilation for evidence of oesophageal intubation

monitor end-tidal carbon dioxide levels; the use of capnography in the emergency intubation is increasingly recommended as a secondary method of confirming correct tube placement. Primary methods such as auscultation are still important, as in the absence of cardiac output there may be little exhaled carbon dioxide to detect. However, a capnograph may also help with ensuring continuing correct placement throughout the arrest and transfer, and presence of exhaled carbon dioxide is an indicator of restoration of cardiac output should it occur.

if in doubt about the position of the endotracheal tube, take it out and oxygenate the patient by another method, bag and mask or surgical airway.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree