Adnexal Masses

Pelvic masses during pregnancy have historically posed diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas for the physician. The first published case of successful surgical removal of an ovarian cyst in a pregnant woman was by Burd in 1846; the patient survived the operation, but aborted a few days later (McKerron, 1906). J. Marion Sims was the first to report the surgical removal of an ovarian tumor from a patient 3 months pregnant who survived and eventually delivered a living child (McKerron, 1906). Among 720 pregnant women with surgically treated adnexal masses reported by McKerron (1906), the maternal mortality rate was 21 percent and the fetal mortality rate was 50 percent.

In later series in which patients with adnexal masses during pregnancy were treated expectantly, a 26 percent maternal mortality rate occurred secondary to hemorrhage, torsion, or suppuration with peritonitis (Patton, 1906). In 1920, Spencer reported that in pregnant patients managed expectantly, 11 percent of adnexal masses underwent torsion, 2.3 percent underwent rupture with significant intraabdominal hemorrhaging, 14.5 percent underwent suppuration, and 5.5 percent caused significant dystocia leading to cesarean delivery. Caverly (1931) subsequently reported a 30 percent spontaneous abortion rate with expectant management of adnexal masses.

As a result of these observations, “expectant management until the second trimester” became the standard therapy for adnexal masses occurring during pregnancy beginning in the early 1900s. Any mass that persisted into the second trimester was removed surgically. This regimen gained popular acceptance not only because of the high maternal complication rate if the mass was not removed, but also because of the significant (2–8 percent) risk of ovarian malignancy in any adnexal mass occurring with pregnancy.

More recent series of pregnant patients with adnexal masses have been reported since 1900 and include those of Ballard (1984), Struyk and Treffers (1984), Hess (1988), Platek (1995), Bromley and Benacerraf (1997), Hill (1998), Bernhard (1999), Whitecar (1999) and their associates. Since McKerron’s monograph was published in 1906, the risk of maternal and fetal mortality has diminished dramatically. Following the introduction of antibiotics and modern blood-banking techniques, reports indicate a low risk of maternal complications and no maternal deaths with elective removal of a persistent adnexal mass. Despite these improvements, adnexal masses during pregnancy still pose clinical and therapeutic dilemmas for clinicians. Marino and Craigo (2000) reviewed this subject.

INCIDENCE

The reported incidence of adnexal masses occurring with pregnancy has varied considerably. Prior to the introduction of ultrasound, Grimes and colleagues (1954) reported the highest incidence of adnexal masses at 1 in 81, or 1.2 percent of pregnancies, in their series of 49 masses reported from private practice. Diagnosis was dependent primarily on clinical evaluation. Since the introduction of ultrasound, the incidence has still varied considerably from 4.3 percent to 1 of 640 pregnancies (Jubb, 1963; Hogston and Lilford, 1986; Lavery and associates, 1986; Nelson and associates, 1986; Thornton and Wells, 1987; Hill and associates, 1998; Bernhard and associates, 1999). The combination of physical and sonographic examination detects most of the 0.5–2.2 percent of pregnancies complicated by an adnexal mass.

The percentage of adnexal masses that are malignant has also varied in the literature. A review of the English literature by Jubb revealed only 24 cases of primary ovarian carcinoma in pregnancy (Jubb, 1963). Roberts’ (1983) review of adnexal masses in pregnancy revealed a 2.2–8 percent malignancy rate, which has been supported by other authors (Struyk, 1984; Thornton, 1987; Hogston, 1986; Hess, 1988; Creasman, 1971; and their associates). Therefore, it is prudent to consider malignancy whenever evaluating adnexal masses in pregnancy due to its frequent occurrence and serious consequences.

INITIAL RECOGNITION

The recognition of an adnexal mass in pregnancy depends upon a careful history, a thorough physical examination, and clinical suspicion. In Dgani and associates’ review (1989), patients with malignant adnexal masses occurring with pregnancy presented with symptoms of pelvic pain, abdominal distension, or pelvic pressure. In contrast, most benign adnexal masses occurring with pregnancy are asymptomatic. Pelvic examination in the first trimester affords the clinician the best opportunity to assess the adnexa and identify a mass. After the first trimester, the increased uterine size and changing location of the adnexa interfere with identification of adnexal abnormalities by either physical or ultrasonographic examination. An attempt should be made to view and evaluate the adnexa as a routine part of obstetric ultrasound examinations, especially those performed in the first trimester, when visualization is best achieved (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 1993).

Whenever an adnexal mass is identified, pelvic examination should include assessment of uterine and adnexal size and the presence of uterine, adnexal, or cul-de-sac irregularity. Additionally, the mobility of the mass should be determined. A rectal examination should also be performed to evaluate the posterior cul-de-sac for masses, tenderness, or fixation of the uterus or adnexa. All patients with a pelvic mass should have a stool guaiac test performed.

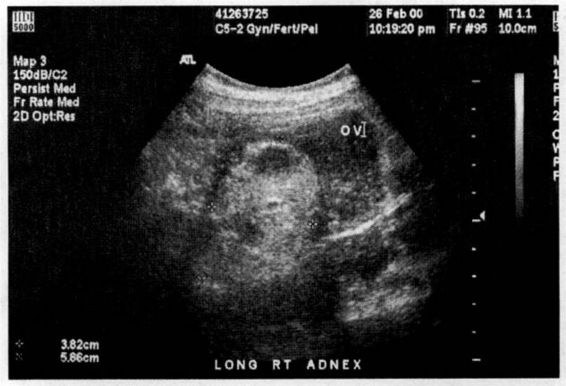

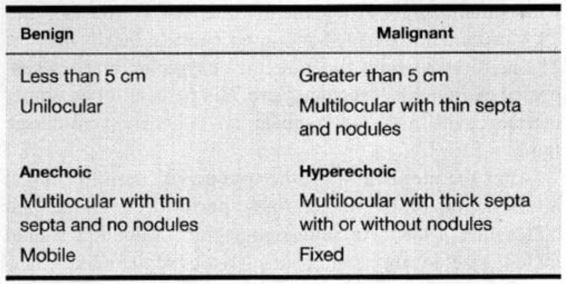

Pelvic masses are often identified during pregnancy as an incidental finding during an ultrasound examination performed for other indications. Ultrasound evaluation of the adnexal mass should include size, location, origin, and specific characteristics including echogenicity, presence or absence of septa, septal characteristics, and the presence or absence of excrescences. As Meire and colleagues’ (1978) study revealed, these characteristics aid in distinguishing between benign and malignant disease (Table 19-1). The ultrasound examination also should include an evaluation to exclude hydatidiform or partial molar pregnancy, conditions that may be the source of large theca lutein cysts in response to high serum HCG concentrations.

EVALUATION

Further evaluation of adnexal masses in gravidas includes basic laboratory, ultrasonographic, and/or radiographic evaluation. In general, a complete blood count, urinalysis, complete chemistry panel, and ultrasound examination should be obtained on all patients with adnexal masses. Tumor markers may be considered if malignancy is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging or other radiographic studies should be considered in those adnexal masses that remain confusing after an initial evaluation.

TUMOR MARKERS

The most common tumor marker used when evaluating an adnexal mass in a nonpregnant patient is the serum CA 125. In nonpregnant patients who have a CA 125 level greater than 65 U/mL, ovarian malignancy was predicted with a sensitivity of 91 percent (Malkasian and colleagues, 1988; Patsner, 1989, 1991). CA125 is also elevated in other disease states, including endometriosis, peritonitis, salpingitis, and tuberculosis, as well as with certain other metastatic nongynecologic and gynecologic cancers (Patsner, 1989). Unfortunately, in the pregnant patient, CA125 is not as sensitive a marker as it is in the nonpregnant patient. Increased levels of CA125 (above 35 U/mL) have been found in both the first and second trimesters of pregnancy (Seki, 1986; Touitou, 1989; and their associates). Touitou and colleagues (1989) noted that even if immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) was used instead of the standard enzyme immunoassay (EIA), the false-positive rates for pregnancy might be lower, but still as high as 2.8 percent (Touitou and associates, 1989).

Sialyl SSEA-1 antigen has also been used as an ovarian tumor marker. Of note is that when combined with CA125 in pregnant patients, this antigen has low false-positive values (Iwanari and associates, 1990; Kobayashi and Kawashima, 1990).

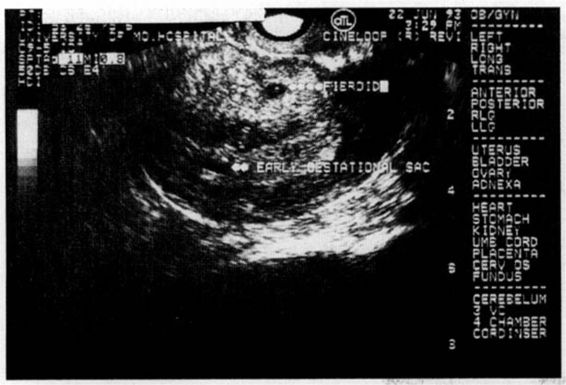

A quantitative β human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) level may also be used as a tumor marker for a molar pregnancy or to exclude ectopic pregnancy as an etiology of adnexal mass (Hay, 1988). If the βHCG level is greater than 1000 U/L (International Reference Preparation, IRP) and transvaginal ultrasound (5–9 MHz probe) reveals no gestational sac, ectopic pregnancy should be considered. A serum βHCG level of 1000 U/L combined with transvaginal sonographic identification of an adnexal mass was diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy with a sensitivity of 97 percent and a specificity of 99 percent (Cacciatore and colleagues, 1990).

Another common test, maternal serum α-fetoprotein, can also be used as a tumor marker in pregnancy or as an indicator of an extrauterine pregnancy as the etiology of adnexal masses. Maternal serum α-fetoprotein is elevated in neural tube or other fetal defects, multiple gestations, germ cell tumors, gastrointestinal tumors, and extrauterine pregnancies (Gonsoulin, 1990; Barett, 1990; and their colleagues), α-Fetoprotein levels may be greater than 1000 ng/mL with maternal germ cell or gastrointestinal tumors (Gonsoulin and associates, 1990).

ULTRASOUND

Sonographic evaluation of the female pelvis is often extremely useful when an adnexal mass is identified (Lavery, 1986; Meire, 1978; Fleischer, 1990; Guy, 1988; Coleman, 1992; and their associates). In the first trimester of pregnancy, transvaginal sonography provides better resolution and closer proximity to the pelvic organs than does transabdominal sonography (Coleman, 1993; Lande, 1988; Lewitt, 1990; Burry, 1993; and their colleagues). With transvaginal ultrasound, significantly more direct signs of an ectopic pregnancy are seen than are seen with abdominal techniques (Weigel and colleagues, 1993). Positive predictive values for ectopic pregnancy are 93.5 percent for an extrauterine double ring, 90.7 percent for inhomogeneous adnexal masses with simultaneous echogenic fluid in the cul-de-sac, and 79.3 percent for isolated inhomogeneous adnexal masses. The predictive values for indirect sonographic hints of suspected extrauterine pregnancy are 78.4 percent for an empty uterine cavity and 87.3 percent for echogenic cul-de-sac fluid.

After the uterus has left the true pelvis, transabdominal ultrasonography is preferentially performed (Lande and colleagues, 1988). An ultrasonographic evaluation should include size, location, and characteristics of the mass. Characteristics include the echogenicity; loculation; density or thickness of septa; presence or absence of solid nodules; evidence of invasion of the capsule; and fixation of the mass. Bromley and Benacerraf (1997) described the ultrasonographic characteristics of adnexal masses that are commonly seen in pregnancy as follows. Mature cystic teratomas, or dermoids, contain a highly echogenic, solid portion with acoustic shadows (Fig. 19-1). Endometriomas are homogenously filled with low-level echoes but no nodulation. A septate cyst contains thin septa, but no nodules or solid components, as compared to simple cysts that are unilocular, anechoic with smooth, internal borders. Solid masses or complex cystic masses with nodulation, irregular borders or thick septations are suggestive of malignancy. When all of these criteria are considered, ultrasound can permit a correct differentiation of malignant from nonmalignant ovarian cysts in up to 91 percent of cases (Meire, 1978; Bromley and Bennaceraff, 1997) (Table 19-1). Most cysts that are anechoic and less than 5 cm will not be malignant (Meire and colleagues, 1978). However, when all anechoic lesions in pregnancies are evaluated, 5 percent have the potential to be malignant (Moyle and associates, 1983).

FIGURE 19-1. Ultrasonographic image of a mature cystic teratoma diagnosed during pregnancy. (Courtesy of PhebeChen, MD.)

TABLE 19-1. Ultrasound Characteristics of Ovarian Masses

Color and pulse Doppler flow studies in combination with two-dimensional ultrasound might be used in the future to evaluate pelvic masses (Schiller and Grant, 1992). In a study by Kurjak and associates (1990), there was some correlation between pelvic mass blood flow and evidence of malignancy. Lower impedance and higher blood velocity due to neovascularization appeared to be correlated with the cases of malignancy (Kurjak and colleagues, 1990). Despite the use of high-resolution ultrasound, with or without color Doppler imaging, 2 of 41 patients with unilocular cysts on ultrasound had tumors of low malignant potential in a recently reported series (Whitecar and colleagues, 1999).

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be considered a useful diagnostic adjunct to ultrasonographic evaluation for an adnexal mass complicating pregnancy (Lubbers, 1988; Kier, 1990; Levine, 2000; and their colleagues). MRI is preferable to computed tomography (CT) because CT uses ionizing radiation and provides minimal discriminatory information because most pelvic masses have a nonspecific appearance (Kier, 1990; Levine, 2000; and their associates). MRI also permits imaging in more than one plane, thus it is particularly good at identifying the origin of the pelvic mass, its contents (particularly absence of hemorrhage), and degenerative or malignant changes (Nyberg, 1987; Lubbers, 1988; Kier, 1990; Al-Awanhi, 1991; Levine, 2000; and their associates). MRI is also useful in diagnosing or distinguishing uterine leiomyomata from more serious pathology, thus preventing unnecessary surgical exploration. One small series reported five pregnant women with adnexal masses suspected to be leiomyomas who underwent MRI. Four patients had evidence of leiomyoma and one had a benign cystic teratoma. Laparotomy was avoided because of the almost certain radiologic findings of a benign process (Curtis and .colleagues, 1993). MRI appears safe for use in pregnancy (Kier, 1990; Lubbers, 1988; Al-Awanhi, 1991; Nyberg, 1987; Weinreb, 1996; Levine, 2000; and their associates; National Radiological Protection Board, 1983). However, despite the lack of evidence of hazards to the embryo or fetus, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on MRI recommends that “MRI scanning in pregnancy only be used during the first trimester when there is a clear medical indication that it offers definitive advantages over other tests” (Kier, 1990; Levine 2000; and their associates).

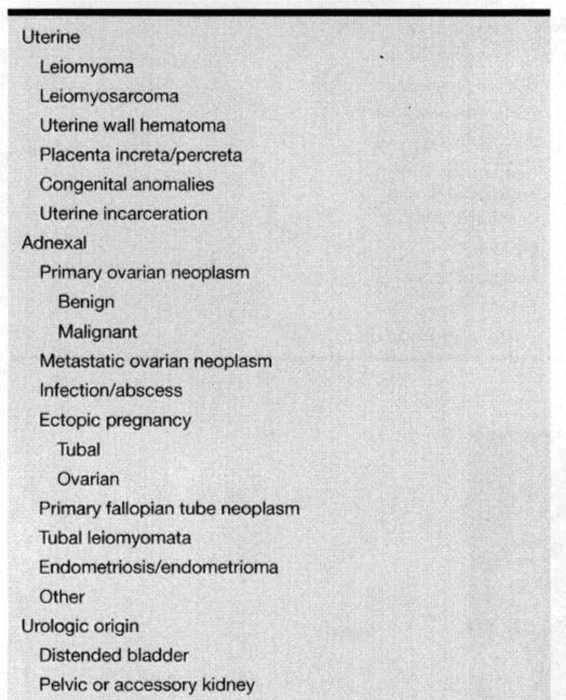

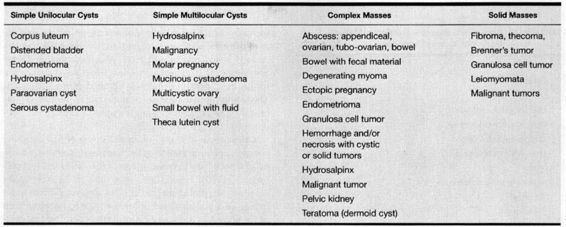

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

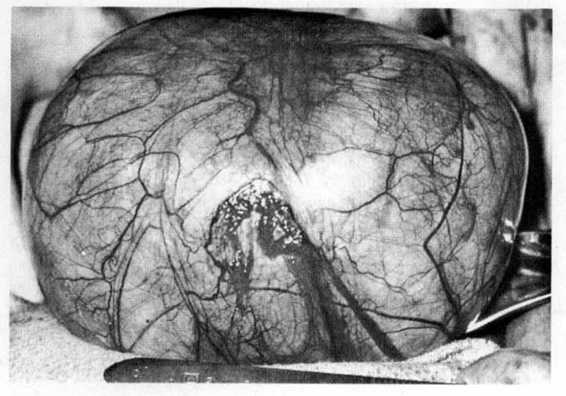

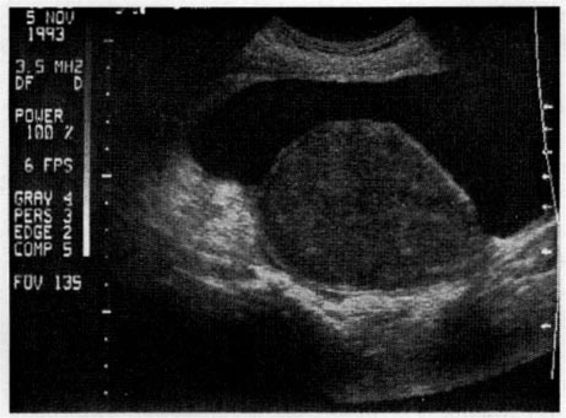

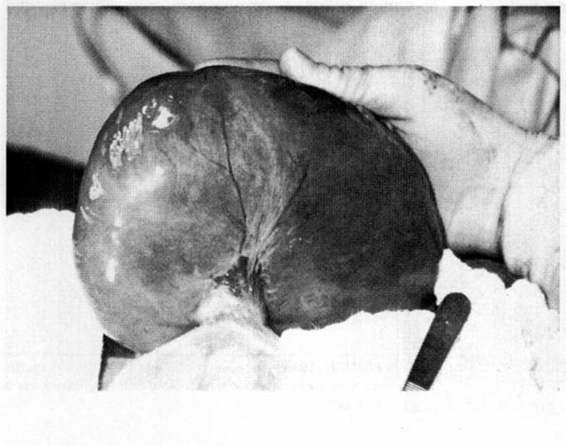

Pelvic masses may arise from the uterus itself or be extrauterine in origin (Table 19-2). Of the uterine masses, leiomyomata are the most common (Marino and Craigo, 2000). Extrauterine masses may arise from bowel, bladder, fallopian tubes, ovaries, or other abdominal organs. They can be grouped into four separate categories based on ultrasonographic evaluation: simple unilocular cysts, simple multilocular cysts, complex masses, and solid masses (Table 19-3). This sonographic classification can narrow the differential diagnosis of the pelvic mass; however, many of the disease processes may fit into more than one sonographic category. For instance, a hydrosalpinx may appear as a unilocular cyst but more often will have the appearance of a complex mass. Similarly, a granulosa cell tumor may appear as a solid or as a complex mass (Table 19-3). Ovarian masses are the most commonly identified extrauterine mass. The specific ovarian lesion most often identified is a mature or benign cystic teratoma (Fig. 19-2) followed by cystadenoma (serous or mucinous; Fig. 19-3) and corpus luteal cyst (Whitecar and colleagues, 1999; Table 19-4).

TABLE 19-2. Differential Diagnosis of Pelvic Masses Occurring During Pregnancy

TABLE 19-3. Sonographic Categories of Pelvic Masses

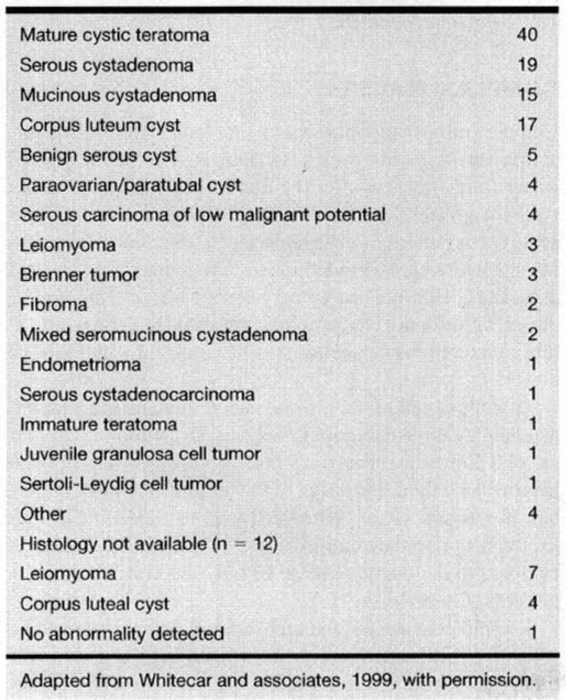

TABLE 19-4. Histologic Diagnoses or Operative Findings of Adnexal Masses (n = 130)

FIGURE 19-2. Teratoma in early pregnancy that underwent acute torsion.

FIGURE 19-3. Serous cystadenoma elcctivcly removed at 15 weeks’ gestation.

Of ovarian masses discovered during pregnancy, 2–8 percent will be malignant (Grimes, 1954; Ballard, 1984; Struyk, 1984; Hess, 1988; White, 1973; McGowan, 1983; Ashkenazy, 1988; Munnell, 1963; Bernhard, 1999; and their colleagues). The incidence of ovarian malignancy in pregnancy has been reported to be between 1 in 1800 (Munnell, 1963; the most often quoted source) and 1 in 25,000 pregnancies (Dgani, 1989; Ashkenazy, 1988; Munnell, 1963; Tawa, 1964; Chung, 1973; Wilson, 1937; Dougherty, 1950; Ballard, 1984; and their associates).

LEIOMYOMAS

Leiomyomas are the most common pelvic mass associated with pregnancy (Figs. 19-4, 19-5, and 19-6). They occur in 0.3–2.6 percent of pregnancies, and usually have no clinical significance (Bezjian, 1984). The usual sonographic appearance of a leiomyoma is a relatively hypoechoic mass lying within the uterine wall with a distinct capsule. Leiomyomas may develop cystic areas as a result of red degeneration, demonstrate echogenic rims corresponding to areas of calcification, or demonstrate heterogeneity (Fleischer, 1990; Lev-Toaff, 1987; and their associates) (Figs. 19-7 and 19-8). They also may be pedunculated and separate from the uterus. In a 1987 study, Lev-Toaff and associates evaluated the behavior of leiomyomas in pregnancy. Contrary to the popularly held belief that fibroids enlarge during pregnancy and regress in the puerperium, Lev-Toaff and associates (1987) noted that in the second trimester, smaller fibroids increased in size, but larger fibroids decreased. During the third trimester all fibroids, regardless of their initial size, decreased in size (Lev-Toaff, 1987; Ahavoni, 1988; and their associates). Ahavoni and associates (1988) noted no increase in size in 78 percent of fibroids detected during pregnancy. Those fibroids that enlarged increased no more than 21 percent. At 6 weeks postpartum, size was the same as that documented during pregnancy.

FIGURE 19-4. Sonographic image of a fibroid uterus with an early gestational sac. Note that the fibroid has a well-delineated capsule.

FIGURE 19-5. Sonographic image of a pedunculated leiomyoma in early pregnancy.

FIGURE 19-6. Pedunculated fibroid from Figure 19-5, which underwent acute torsion in pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree