Chapter 37 Abused and Neglected Children

Definitions

Incidence and Prevalence

Etiology

Child maltreatment seldom has a single cause; rather, multiple and interacting biopsychosocial risk factors at 4 levels usually exist. At the individual level, a child’s disability or a parent’s depression or substance abuse predispose a child to maltreatment. At the familial level, intimate partner (or domestic) violence presents risks for children. Influential community factors include stressors such as dangerous neighborhoods or a lack of recreational facilities. Professional inaction may contribute to neglect, such as when the treatment plan is not clearly communicated. Broad societal factors, such as poverty and its associated burdens, also contribute to maltreatment. WHO estimates the rate of homicide of children is approximately twofold higher in low-income compared to high-income countries (2.58 vs 1.21 per 100,000 population), but clearly homicide occurs in high-income countries (Table 37-1). Children in all social classes can be maltreated, and child health care professionals need to guard against biases concerning low-income families.

Table 37-1 CHILD MALTREATMENT DEATHS BY NATION

| COUNTRY | DEATHS PER 100,000 CHILDREN* |

|---|---|

| Spain | 0.1 |

| Greece | 0.2 |

| Italy | 0.2 |

| Ireland | 0.3 |

| Norway | 0.3 |

| Netherlands | 0.6 |

| Sweden | 0.6 |

| Korea | 0.8 |

| Australia | 0.8 |

| Germany | 0.8 |

| Denmark | 0.8 |

| Finland | 0.8 |

| Poland | 0.9 |

| UK | 0.9 |

| Switzerland | 0.9 |

| Canada | 1.0 |

| Austria | 1.0 |

| Japan | 1.0 |

| Slovak Republic | 1.0 |

| Belgium | 1.1 |

| Czech Republic | 1.2 |

| New Zealand | 1.3 |

| Hungary | 1.3 |

| France | 1.4 |

| USA | 2.4 |

| Mexico | 3.0 |

| Portugal | 3.7 |

* Deaths include obvious maltreatment and those of undetermined intent.

From UNICEF: A league table of child maltreatment deaths in rich nations. In Inocenti Report Card No 5, Florence, September 2003, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Figure 1b, p 4.

Clinical Manifestations

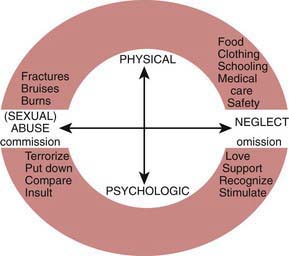

Child abuse and neglect can manifest in many different ways (Fig. 37-1). With regard to physical abuse, a critical element is the lack of a plausible history other than inflicted trauma. As with any medical condition, the onus is on the clinician to carefully consider the differential diagnosis and not jump to conclusions.

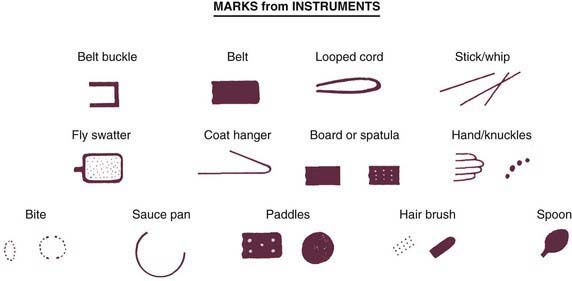

Bruises are the most common manifestation of physical abuse. Features suggestive of inflicted bruises include (1) bruising in a preambulatory infant (occurring in just 2% of infants), (2) bruising of padded and less exposed areas (buttocks, cheeks, under the chin, genitalia), (3) patterned bruising or burns conforming to shape of an object or ligatures around the wrists (Figs. 37-2 and 37-3), and (4) multiple bruises, especially if clearly of different ages. Estimating the age of bruises needs to be done cautiously. Red suggests less than a week, yellow suggests more than 1-2 days. It is very difficult to precisely determine the ages of bruises.

A careful history of bleeding problems in the patient and first degree relatives is needed. If a bleeding disorder is suspected, a platelet count, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio (the ratio of the prothrombin time to a control sample, raised to the power of the International Sensitivity Index), and partial thromboplastin time should be obtained (Chapter 469). More extensive testing should be considered in consultation with a hematologist.

Bites have a characteristic pattern of 1 or 2 opposing arches with multiple bruises (see Fig. 37-2). They can be inflicted by an adult, another child, an animal, or the patient. Bites by a child (younger than approximately 8 yr with primary teeth) typically have a distance of less than 2.5 cm between the canines—often the most prominent bruises. The appearance of animal bites is variable (Chapter 705); they usually have narrower arches than human bites and are often deep. Self-inflicted bites are on accessible areas, particularly the hands. Adult bites raise concern for abuse. Multiple bites by another child suggest inadequate supervision and neglect.

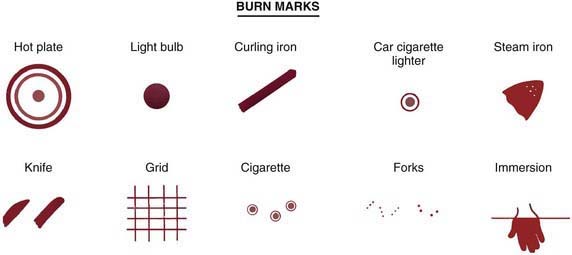

Burns may be inflicted or due to inadequate supervision. Scalding burns may result from immersion or splash (Fig. 37-4; also see Fig. 37-3). Immersion burns, when a child is forcibly held in hot water, show clear delineation between the burned and healthy skin and uniform depth (see Fig. 37-4). They may have a sock or glove distribution. Splash marks are usually absent, unlike when a child inadvertently encounters hot water. Symmetrical burns are especially suggestive of abuse as are burns of the buttocks and perineum. Although most often accidental, splash burn may also result from abuse. Burns from hot objects such as curling irons, radiators, steam irons, metal grids, hot knives, and cigarettes leave patterns representing the object. A child is likely to try to escape from a hot object; thus burns that are extensive and deep reflect more than fleeting contact and are suggestive of abuse.

Neglect frequently contributes to childhood burns (Chapter 68). Children, home alone, may be burned in house fires. A parent taking drugs may cause a fire and may be unable to protect a child. Exploring children may pull hot liquids left unattended onto themselves. Liquids cool as they flow downward so that the burn is most severe and broad proximally. If the child is wearing a diaper or clothing, the fabric may absorb the hot water and cause burns worse than otherwise expected. Some circumstances are difficult to foresee, and a single burn resulting from a momentary lapse in supervision should not automatically be seen as neglectful parenting.

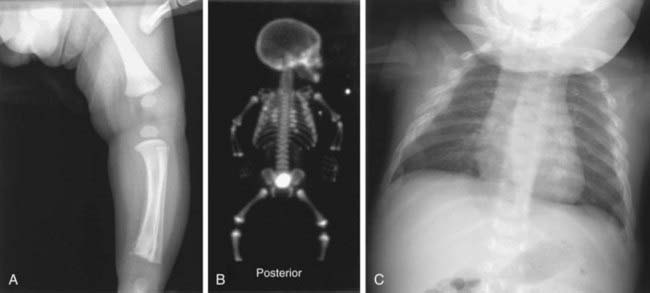

Fractures that strongly suggest abuse include: classic metaphyseal lesions, posterior rib fractures, and fractures of the scapula, sternum, and spinous processes, especially in young children (Table 37-2, Fig. 37-5). These fractures all require more force than would be expected from a minor fall or routine handling and activities of a child. Rib and sternal fractures rarely result from cardiopulmonary resuscitation, even when performed by untrained adults. In abused infants, rib, metaphyseal, and skull fractures are most common. Femoral and humeral fractures in nonambulatory infants are also very worrisome for abuse. With increasing mobility and running, toddlers can fall with enough rotational force to cause a spiral, femoral fracture. Multiple fractures in various stages of healing are suggestive of abuse; nevertheless, underlying conditions need to be considered. Clavicular, femoral, supracondylar humeral, and distal extremity fractures in children older than 2 yr are most likely noninflicted unless they are multiple or accompanied by other signs of abuse. Few fractures are pathognomonic of abuse; all must be considered in light of the history.

Table 37-2 SKELETAL INJURIES FROM ABUSE

COMMON

LESS COMMON

UNCOMMON

* High specificity for abuse in infants.

Modified from Slovis TL, editor: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, vol 2, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby/Elsevier.

The evaluation of a fracture should include a skeletal survey in children less than 2 yr of age when abuse seems possible. Multiple films with different views are needed; “babygrams” (1 or 2 films of the entire body) should be avoided. If the survey is normal, but concern for an occult injury remains, a radionucleotide bone scan should be performed to detect a possible acute injury (see Fig. 37-5). Follow-up films after 2 wk may also reveal fractures not apparent initially (see Fig 37-5).

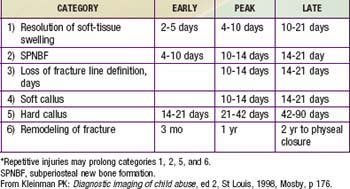

In corroborating the history and the injury, the age of a fracture can only be crudely estimated (Table 37-3). Soft-tissue swelling subsides in 2-21 days. Periosteal new bone is visible within 4-21 days. Loss of definition of the fracture line occurs between 10-21 days. Soft callus can be visible after 10 days and hard callus between 14-90 days. These time frames are shorter in infancy and longer in children with poor nutritional status or a chronic underlying disease. Fractures of flat bones such as the skull do not form callus and cannot be aged.

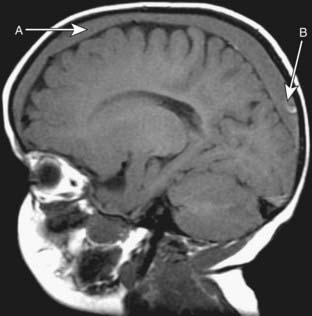

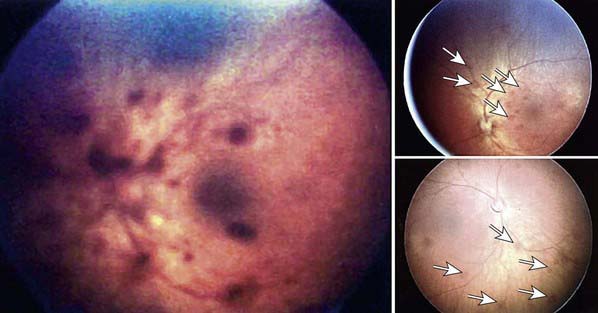

Abusive head trauma (AHT) results in the most significant morbidity and mortality. Abusive injury may be caused by direct impact, asphyxia, or shaking. Subdural hematomas (Fig. 37-6), retinal hemorrhages (especially when extensive and involving multiple layers) (Fig. 37-7), and diffuse axonal injury strongly suggest AHT, especially when they co-occur (Chapter 63). The poor neck muscle tone and relatively large heads of infants make them vulnerable to acceleration-deceleration forces associated with shaking, leading to AHT. Children may lack external signs of injury, even with serious intracranial trauma. Signs and symptoms may be nonspecific, ranging from lethargy, vomiting (without diarrhea), changing neurologic status or seizures, and coma. In all preverbal children, an index of suspicion for AHT should exist when children present with these signs and symptoms.

Retinal hemorrhages are an important marker of AHT (see Fig. 37-7). Whenever AHT is being considered, a dilated indirect ophthalmologic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist should be performed. Although retinal hemorrhages can be found in other conditions, hemorrhages that are multiple, involve more than one layer of the retina, and extend to the periphery are very suspicious for abuse. The mechanism is likely repeated acceleration-deceleration due to shaking. Traumatic retinoschisis points strongly to abuse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree