Chapter 21 Abnormal fetal presentations

OCCIPITOPOSTERIOR PRESENTATIONS

In about 10% of pregnancies the fetal head enters the maternal pelvis with its occiput in one of the posterior segments of the pelvis (see Fig. 8.4, p. 70).

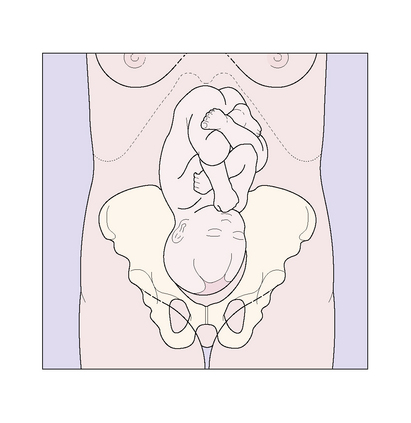

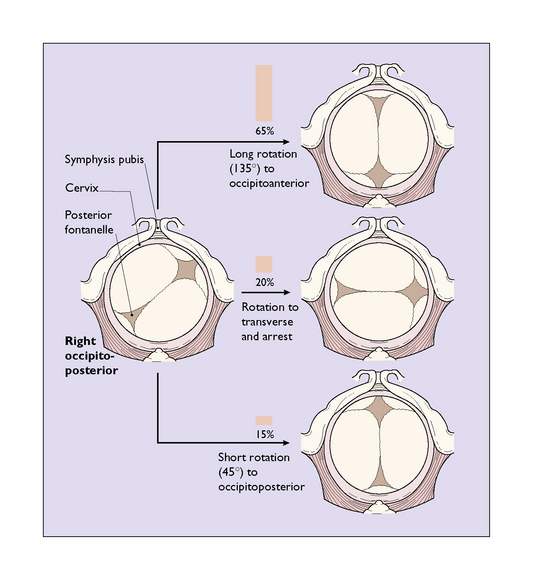

The diagnosis may be made on abdominal palpation when the fetal back is felt in one of the mother’s flanks, the fetal heart being loudest here (Fig. 21.1). In labour, vaginal examination provides more information, the occiput and the anterior fontanelle being identified (Fig. 21.2).

During labour the fetal head is forced deeper into the pelvis, and usually flexes on the fetal neck. Once full dilatation of the cervix has occurred its progress may be in one of three ways (Fig. 21.2):

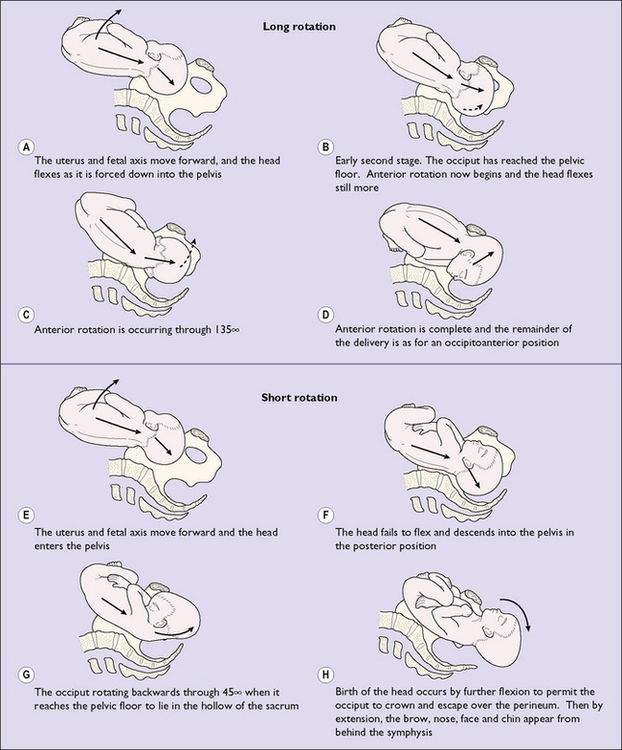

Thus, in most cases the fetal head undergoes a long or a short rotation (Fig. 21.3).

Management of occipitoposterior presentations

There is no proven management that encourages rotation to an occipitoanterior position before labour starts. Once begun, the duration of labour tends to be longer in occipitoposterior positions and the mother requires more support, analgesia and hydration. Progress is monitored using a partogram. The descent of the head, and its position, are checked regularly. Any marked delay in the first stage of labour leads to prolonged labour (see p. 178–179) and a decision has to be made whether to continue or to perform a caesarean section. Delay in the second stage of labour of more than 1.5–2 hours’ duration indicates the need for help to deliver the baby. If the fetal head undergoes the long rotation a spontaneous vaginal delivery may be expected. This occurs in 65% of cases. If the fetal head undergoes the short rotation and descends to the pelvic floor in the posterior position, the infant may be born spontaneously (8% of all cases) or may need help by forceps or vacuum (7%). On the other hand, the fetus may not descend much beyond the ischial spines and a manual rotation and forceps delivery, Kjelland’s forceps delivery or vacuum extraction may be necessary (see Ch. 22). These procedures are also required if the fetal head arrests in a transverse diameter of the pelvis. Between 5 and 10% of babies who are occipitoposterior are delivered by caesarean section.

BREECH PRESENTATIONS

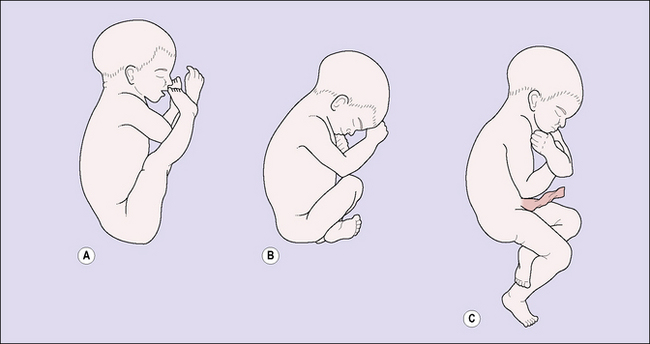

The frequency of breech presentation falls as pregnancy advances. At the 30th week of pregnancy 15% of fetuses present as a breech; by the 35th week the proportion has fallen to 6%, and by term only 3% present as a breech. Most of these babies spontaneously turn to become cephalic. If the presentation is still a breech at the 37th week many obstetricians attempt a cephalic version, which is described on pages 197–199. Version is easier if the fetus has flexed legs, one of the three types of breech presentation (Fig. 21.4).

Management of breech births

Vaginal breech birth

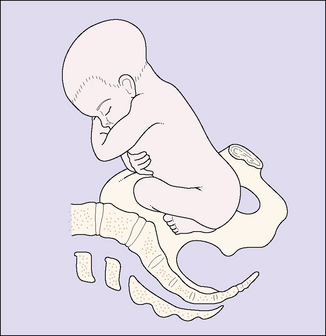

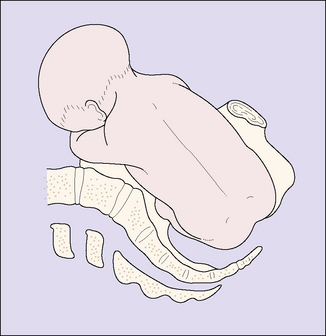

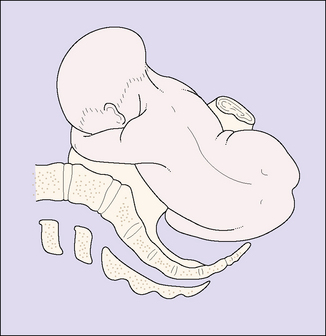

It is still important to understand the management and the mechanism of a breech birth, as an unexpected breech presentation may occur at full cervical dilatation with insufficient time to organize a caesarean section. This is shown in Figures 21.5–21.14 and is described in the captions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree