increase in point prevalence after age 50 years that may be related to changes in immune and hormonal status that occur following menopause.16, 17, 18 Important to also note is a change in lifestyle or sexual partners in women of any age, which may lead to new HPV infection.

TABLE 5.1 High-Risk and Low-Risk Types of Human Papillomavirus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

environment for viral infection are the cervix, vaginal, vulva, anus, and oropharyngeal mucosa surfaces. Attempts at culturing HPV from tissue samples or growing the virus in tissue culture have been unsuccessful thus far. In addition, the epithelium appears to shield the virus from the immune response, making serologic tests relatively unreliable.31,32 At present, the diagnosis of HPV infection requires direct detection of viral DNA within the nucleus of an infected cell. Samples from the transformation zone (TZ) of the cervix collected by cytobrush are generally a good source of infected cells. The relationship between HPV infection and subsequent development of anogenital neoplasia is so compelling that the possibility of HPV-negative LSIL as a distinct biological entity is now shown to be unfounded. Most such findings appear to stem from cytologic misinterpretations or falsely negative HPV tests.33

TABLE 5.2 Natural History of Cervical Lesions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

as well as inaccurate and nonreplicable interpretation. Studies in the United Kingdom have shown a sensitivity rate of conventional Pap smears of 72% and specificity of 94%.38 Overall, about two-thirds of the false-negative Pap tests were related to sampling errors and the remaining one-third due to laboratory detection error. Liquid-based screening systems were developed to improve the transfer of cells from the collection device to the slide, provide uniformity of the cell population in each sample, decrease obscuration of menstrual blood flow, and thus decrease interpretational errors. Studies have shown liquid-based cytology to be better at providing an adequate specimen and detecting ASCUS, LSIL, and glandular abnormalities. This method is not better at detecting the clinically relevant HSIL.39, 40, 41, 42, 43

cancer. HPV-18 causes 10 to 15% of cervical cancers, including a greater proportion of glandular cancers. These subtypes can be specifically tested for on the cobas HPV test or Cervista 16/18 test. The remaining 25 to 35% of cervical cancer is caused by 13 other genotypes.50, 51, 52

TABLE 5.3 Summary of Recommendations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

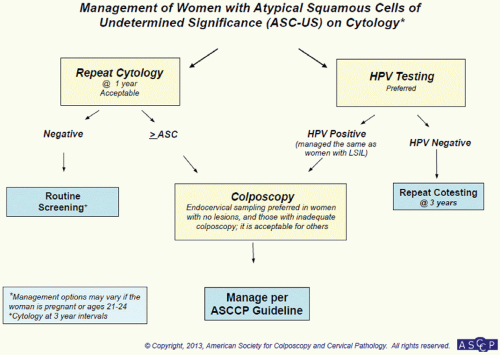

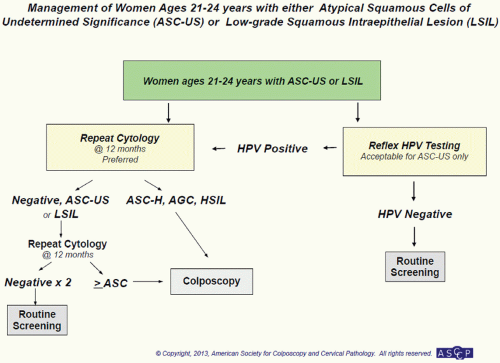

(ACS) amended its previous recommendations for screening women for cervical cancer. This was further revised in 2012 (see Table 5.3).56 The first major change involves initiation of screening. Previous guidelines recommended that women begin screening at age 21 years or 3 years after age at first coitus and that screening be continued annually until age 30 years. The current recommendations now instruct practitioners to begin screening at age 21 years and screen every 3 years thereafter until age 30 years. Initiation of screening is independent of age of first coitus and should only commence at age 21 years. In the case that an adolescent presents with known ASCUS or LSIL, cytology should be repeated in 1 year. Those that present with HSIL should

go to colposcopy. The evidence behind changing screening initiation age and interval is two-fold. First, given the prevalence of initial HPV infection in adolescents and those younger than 21 years, many young women will transiently be infected with HPV. Most of these women will clear the infection and not go on to develop cervical dysplasia. Screening before 21 years of age would therefore increase the number of surgical interventions for transient disease with virtually no risk for the development of invasive cervical cancer. Secondly, yearly screening between the ages of 21 and 30 years has not been shown to decrease the incidence of cervical cancer given the 5 to 10 years needed to develop disease.

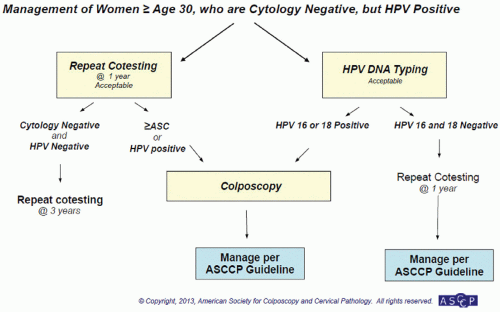

testing for 16/18. If HPV-16/18 are present, the patient should be immediately referred for colposcopy. If they are HPV-16/18-negative, they can be followed up in 12 months with cotesting (see Fig. 5.3).

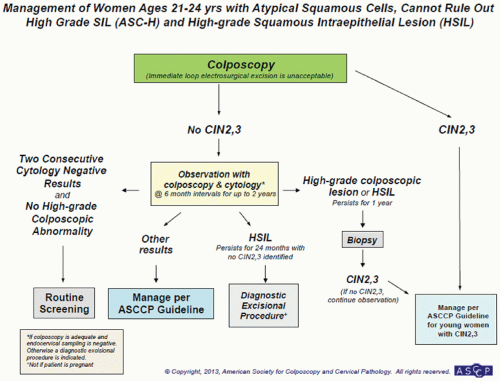

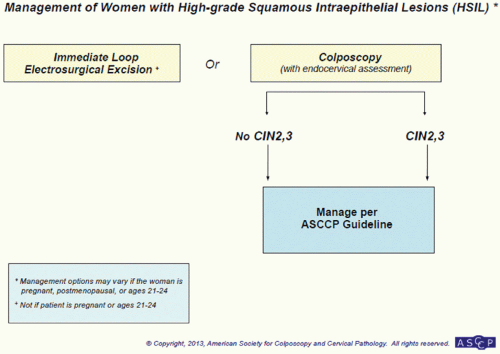

FIGURE 5.10 Management of women with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). (Reprinted from The Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, Volume 17, Number 5, with the permission of ASCCP @ American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology 2013. No copies of the algorithms may be made without the prior consent of ASCCP.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|