Abdominal Pregnancy

An abdominal pregnancy is an ectopic pregnancy in the truest sense of the term because it is a pregnancy lying totally outside of the reproductive tract (Fig. 20-1). There are few obstetric complications that portend the need for massive blood transfusions more than this form of ectopic pregnancy. Costa and colleagues (1991) provided an excellent review on this topic. According to them, Arab writer Albucasis, in 963 AD, was probably the first to describe an abdominal pregnancy. He described the discharging of fetal parts through the abdominal wall. The first record of a “true primary peritoneal pregnancy” was by Gallabin (1903). Since then, the literature is replete with articles on this subject. Fortunately, this complication is rare.

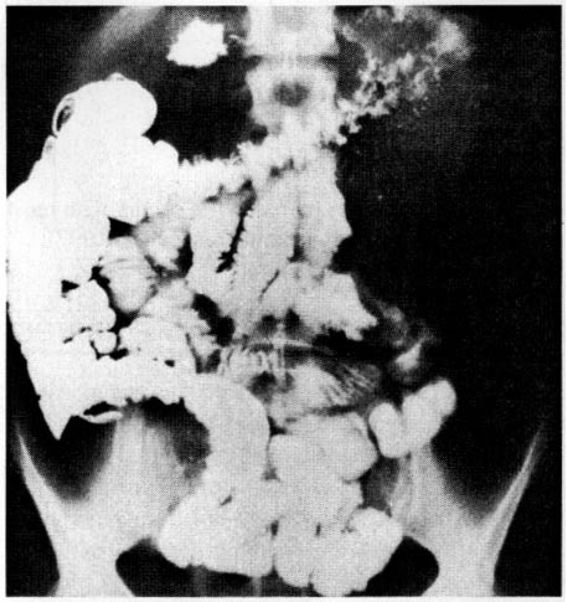

FIGURE 20-1. Abdominal pregnancy at term. Placenta is implanted on bladder and anterior abdominal wall. The enlarged, flattened uterus is located posteriorly in the cul-de-sac. Cervix and vagina are also dislodged posteriorly by the pregnancy.

INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

The incidence of abdominal pregnancy has been reported to range from 1 in 3300 to 1 in 25,000 births (Beacham and associates, 1962; Cunningham and colleagues, 1993). Atrash and associates (1987), using data from the Centers for Disease Control’s Abortion and Ectopic Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance Systems and the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1970 to 1983, reported 5221 abdominal pregnancies and 47,869,951 deliveries for a ratio of 10.9 per 100,000 births. The rate appears to have increased with the availability of assisted reproductive techniques such as in vitro fertilization and gamete intrafallopian transfer (Ferland and associates, 1991; Vignali and colleagues, 1990; Fisch and coworkers, 1996). Moreover, the frequency of all ectopic pregnancies in the United States has increased over the past three decades (Costa and coworkers, 1991). Atrash and colleagues (1987) estimated that there are approximately 9.2 abdominal pregnancies for every 1000 ectopic pregnancies.

Abdominal pregnancy is also associated with endometriosis, tuberculosis, and the use of intrauterine devices (Børlum and Blom, 1988; Goldman and colleagues, 1988; Vignali and associates, 1990). Durukan and associates (1990) reported a case of abdominal pregnancy 10 years after treatment for pelvic tuberculosis.

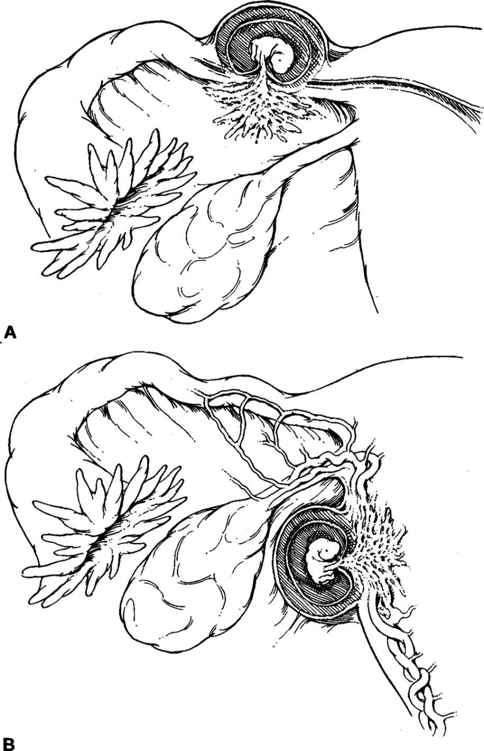

In most cases, an abdominal pregnancy arises as a secondary implantation from a ruptured tubal pregnancy (Fig. 20-2). Very rarely, primary implantation may occur on the peritoneal surface (Fig. 20-3). For example, Goldman (1988) and Thomas (1991) and their colleagues reported a total of six cases of documented primary abdominal pregnancy.

FIGURE 20-2. Secondary abdominal pregnancy. A. There is partial abortion from a tubal, cornual, or uterine pregnancy. B. Placental growth continues outside original confines.

FIGURE 20-3. Primary abdominal pregnancy, characterized by peritoneal implantation of the blastocyst.

An abdominal pregnancy may implant anywhere in the abdominal or pelvic cavity. Implantation is probably more common in adjacent pelvic surfaces such as the posterior aspect of the broad ligament and uterus (Figs. 20-1 and 20-4). As shown in Figures 20-5 and 20-6, the site of implantation may involve extrapelvic organs such as the small and large intestine, liver, and spleen (Martin, 1988; Salinas, 1985; and their associates).

FIGURE 20-4. Sites of reported primary pelvic peritoneal pregnancies (filled circles). (Reprinted from Friedrich and Rankin, 1968, with permission.)

FIGURE 20-5. Barium small-bowel follow-through showing extrinsic compression of terminal ileum and cecum from the abdominal pregnancy. (Reprinted from Salinas and colleagues, 1985, with permission.)

FIGURE 20-6. Resection of ileum and mass containing organized blood clots. Both are cut sagittally. Arrow shows opening of lumen. (Reprinted from Salinas and colleagues, 1985, with permission.)

DIAGNOSIS

The early diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy is difficult at best, and there must be a high index of suspicion if the diagnosis is to be made preoperatively. Because abdominal pregnancy is a life-threatening condition in most cases, it is of paramount importance to entertain the diagnosis when considering the differential for abdominal pain during pregnancy. Most often abdominal pregnancy is an incidental finding at the time of sonography or at laparotomy for other suspected conditions. Women with abdominal pregnancies who present in the first trimester may manifest signs and symptoms similar to those of a ruptured tubal pregnancy. These include amenorrhea, abdominal pain, abnormal bleeding, and a positive pregnancy test (Alto, 1990).

Diagnosis after the first trimester presents a much greater challenge and may be in error in many cases (Costa and colleagues, 1991). For example, in one report by Rahman and associates (1982) involving 10 women, a diagnostic error of 60 percent was reported. Delke and colleagues (1982) reported their experience with 10 cases of abdominal pregnancy. Nine of these cases had a history consistent with a ruptured tubal pregnancy or abortion in early pregnancy. Abdominal pregnancy was suspected in 5 of these 10 women and the correct diagnosis was made between 16 and 24 weeks gestation. However, in the remaining five women, there was a considerable delay in diagnosis.

SYMPTOMS

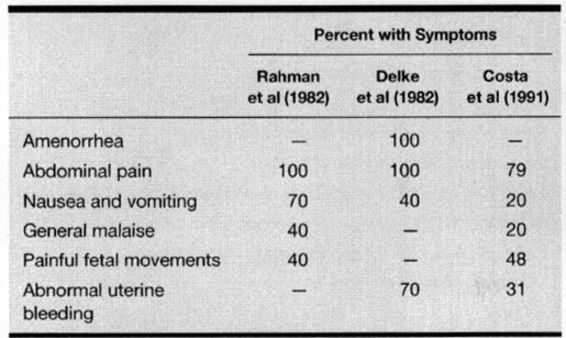

Like the symptoms of an early tubal pregnancy, women with abdominal pregnancy often experience abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, general malaise, amenorrhea, and abnormal early pregnancy bleeding (Table 20-1). Abdominal pain was present in all women with an abdominal pregnancy reported by both Rahman (1982) and Delke (1982) and their colleagues. Moreover, abdominal pain was a complaint in almost 80 percent of women reviewed by Costa and associates (1991). Other clinical symptoms include flatulence, constipation, and diarrhea. Unfortunately, many of the symptoms associated with abdominal pregnancy are also commonly present in women with an intrauterine pregnancy. Rectal bleeding is a rare symptom of abdominal pregnancy secondary to placental invasion of the rectal wall (Saravanane and associates, 1997). Massive blood-stained ascites has also been reported with an abdominal pregnancy (Ross and colleagues, 1997). Interestingly, fetal movement, which is most often considered a reassuring sign in pregnancy, may be associated with significant pain in 40 to 50 percent of women with an abdominal pregnancy (Rahman and associates, 1982; Costa and colleagues, 1991; and their colleagues). Some women may simply complain that “the pregnancy does not feel right” (Cunningham and coworkers, 1997).

TABLE 20-1. Symptoms of Abdominal Pregnancy

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

There are few, if any, conclusive or pathognomonic findings or signs on physical examination in women with abdominal pregnancies. In the series reported by Rahman and colleagues (1982), abdominal tenderness (100 percent), abnormal fetal position (70 percent), and cervical displacement (40 percent) were the most frequent clinical findings.

Although the ease of palpation of fetal parts and position is often listed as a useful finding for the diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy, in actual clinical practice it is not very reliable. Palpation of fetal parts is relatively easy in many women with normal pregnancies. One sign that might cause an increased suspicion is failure of abdominal massage over the pregnancy to stimulate contractions as occurs with most normal pregnancies (Cunningham and associates, 1997).

LABORATORY AND ULTRASOUND FINDINGS

There are few, if any, laboratory tests that are diagnostic of abdominal pregnancy; indeed, most of the routine tests are normal. Delke and colleagues (1982) reported that 4 of 10 women had anemia defined as a hemoglobin level less than 11 g/dL. Abdominal pregnancy has been reported to be associated with a marked elevation of maternal serum α-fetoprotein (Hage and associates, 1988; Tromans and colleagues, 1984; Bombard and coworkers, 1994). Amnionic fluid α-fetoprotein was normal even though the maternal serum α-fetoprotein was elevated in three women with abdominal pregnancies reported by Shumway and associates (1996). This elevated maternal serum α-fetoprotein seems to correlate with more extensive placental movement of abdominal viscera.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree