Abdominal Myomectomy and Uterine Reconstruction for Intramural Myomas

M. Jonathon Solnik

Ricardo Azziz

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been a shift toward offering minimally invasive treatment options for women with reproductive disorders. Fibroid-specific therapies have likewise evolved to include uterine fibroid embolization and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided focused ultrasound. Although any form of therapy should only be directed toward women who are symptomatic, the prevalence of fibroids in reproductive-aged women and number of women treated annually remains high. Consequently, myomectomy remains the mainstay for women who wish to preserve their ability to conceive or are themselves experiencing subfertility. The objective of the clinician is to offer the approach that will best treat the patient’s condition while minimizing the adverse surgical and reproductive outcomes that may follow myomectomy.

Women are often asymptomatic, and fibroids may be detected during routine gynecologic examination or are incidentally noted on imaging studies ordered for unrelated indications. Others will have mass-related complaints such as heaviness, urinary frequency, constipation, or low back pain. Diagnostic considerations then are reliant on the clinical acumen of the treating physician since functional complaints such as these may be visceral in origin, and surgery will less likely result in effective resolution of the patient’s complaints. More reliable symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea, or cyclic cramping. If bleeding is irregular or unpredictable, however, causes of oligo-anovulation should first be considered since bleeding disorders related to fibroids tend to be ovulatory and heavy, representative of an anatomic, not endocrine, etiology. Other sources of pain should also be entertained since treatment may be options other than surgery. The role of fibroids in the setting of subfertility remains less clear, but there is sufficient evidence to support myomectomy when the fibroid is submucosal in location, or intramural and distorting the endometrial cavity.

Today there are a number of approaches that effectively destroy myomas more or less noninvasively (e.g., uterine artery embolization, high-intensity focused ultrasound, and cryomyolysis), although these are appropriate only for women who do not desire subsequent fertility. Myomectomy and uterine reconstruction continues to be the procedure of choice for women desiring fertility or the preservation of reproductive potential. Abdominal myomectomy remains the preferred surgical approach for women with multiple or larger tumors, and is the focus of this chapter.

Alternative approaches such as laparoscopic-assisted (see below) or minilaparotomy myomectomy provide effective treatment with well-described advantages with regard to postoperative recovery, but many women will not qualify as surgical candidates, and concerns regarding the potential for subsequent uterine rupture remain unanswered. Although abdominal myomectomy is often regarded as a single procedure, we need to understand that it also involves careful uterine reconstruction, perhaps

the most important part of the surgery. In this chapter, we describe one method of performing an abdominal myomectomy, adhering to microsurgical principles (see Chapter 22) and restoring myometrial anatomy.

the most important part of the surgery. In this chapter, we describe one method of performing an abdominal myomectomy, adhering to microsurgical principles (see Chapter 22) and restoring myometrial anatomy.

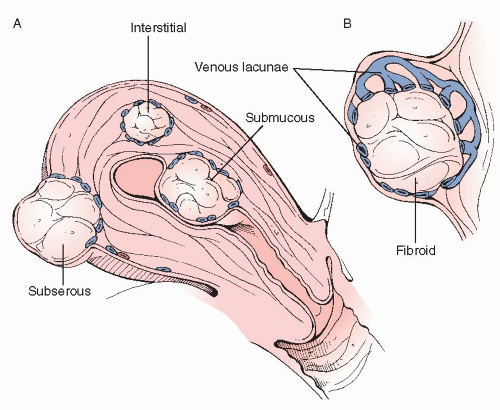

To ensure optimum surgical results, surgeons should clearly understand the anatomy of the myometrium and of myomas. Microscopically, leiomyomas are composed of dense whorls of smooth muscle cells with minimal intervening collagen. The smooth muscle cells of leiomyomata have increased nuclear size, more mitochondria, and increased free ribosomes. Anatomically, myomas are located throughout, and are classified as such, including submucosal (sessile and pedunculated), intramural, and subserosal (sessile, pedunculated, intraligamentous, and parasitic). Leiomyomas also degenerate, as they frequently outgrow their blood supply, since blood vessels do not grow into the mass (see below). Degeneration can be hyalinized, hemorrhagic, carneous, cystic, or caseous.

Most importantly, myomas are not truly encapsulated; rather they are surrounded by a layer of hypertrophied smooth cells of normal myometrium, forming a pseudocapsule, which contains flattened vessels (venous lacunae) (Figure 28.1). This web of flattened vessels surrounds the fibroid, which will often outstrip its blood supply and begin to degenerate. It is this latter anatomy that needs to be kept in mind when performing an abdominal myomectomy.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Unlike many other surgical procedures, preoperative counseling with regard to postoperative reproductive outcomes is requisite in patients undergoing myomectomy. Aside from the typical surgical risks, a thorough discussion should include the possibility of adnexal adhesions resulting in obstructive processes, possible hydrosalpinx formation, and tubal-factor infertility. In patients who are planning for advanced reproductive techniques whereby tubal transport is less of a concern, intrauterine synechiae (Asherman syndrome) remains a well-described phenomenon when the endometrial cavity is breached upon enucleation of a myoma. A discussion regarding when to conceive and how to deliver should the patient become pregnant should also take place, given the need for myometrial repair and risk of subsequent uterine rupture. Finally, patients should be counseled that, because of the nature of myomas, trying to safely create a “myoma-free” uterus may, in some patients, not be a realistic goal.

Preoperatively, it will be most important for the surgeon to obtain an accurate three-dimensional picture of the uterine anatomy. Transvaginal ultrasound is an effective assessment tool for women with abnormal uterine bleeding. However, further evaluation is often warranted, which may include sonohysterography. Sonohysterography can clearly delineate intracavitary

lesions, and has the ability to detect the percentage of the fibroid that is intramural. Historically, the use of hysterosalpingography (HSG) has been described for the preoperative assessment of the uterine cavity, although its value has lessened considerably, with the introduction of the above imaging techniques, which avoid radiation exposure and offer fewer risks, especially if tubal patency is not in question.MRI, although useful in planning for an operative hysteroscopic or laparoscopic myomectomy, provides less value in the planning of abdominal procedures. Images should be available in the operating room to guide the myomectomy.

lesions, and has the ability to detect the percentage of the fibroid that is intramural. Historically, the use of hysterosalpingography (HSG) has been described for the preoperative assessment of the uterine cavity, although its value has lessened considerably, with the introduction of the above imaging techniques, which avoid radiation exposure and offer fewer risks, especially if tubal patency is not in question.MRI, although useful in planning for an operative hysteroscopic or laparoscopic myomectomy, provides less value in the planning of abdominal procedures. Images should be available in the operating room to guide the myomectomy.

Long-acting GnRH analogues (e.g., leuprolide 3.75 mg/month × 3 months) can be used to reduce the size of myomas and uterine vascularity prior to the procedure. However, this therapy also may make it more difficult to detect the plane between normal, albeit compressed myometrium, and myoma. In turn, since blood loss can be significant in cases with large and numerous fibroids, consideration toward use of cell-saver devices should be given and planned according to institutional policy. Following is a brief description of the surgical procedure (see also video: Abdominal Myomectomy and Uterine Reconstruction for Intramural Myomas).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

1. Operative access and patient preparation:  The surgical approach typically begins with a transverse abdominal incision (Pfannenstiel or Maylard) unless exam under anesthesia reveals pathology more safely approached through a midline incision. Patients with deep posterior tumors, especially if large, may pose a formidable obstacle for the surgeon as these are not only difficult to visualize (bony pelvic inlet, sigmoid/colon/rectum), but even if successfully enucleated, may be exceedingly difficult to repair unless a lengthy fascial incision is made. Patient habitus, such as those with a longer distance between anterior superior iliac spines and shorter distance from the pubic symphysis to umbilicus may favor a transverse incision regardless of size or location of the fibroids. If a Pfannenstiel incision is first created, another option is to convert to a Cherney incision, rather than Maylard, in order to preserve the vascular supply to the anterior rectus sheath.

The surgical approach typically begins with a transverse abdominal incision (Pfannenstiel or Maylard) unless exam under anesthesia reveals pathology more safely approached through a midline incision. Patients with deep posterior tumors, especially if large, may pose a formidable obstacle for the surgeon as these are not only difficult to visualize (bony pelvic inlet, sigmoid/colon/rectum), but even if successfully enucleated, may be exceedingly difficult to repair unless a lengthy fascial incision is made. Patient habitus, such as those with a longer distance between anterior superior iliac spines and shorter distance from the pubic symphysis to umbilicus may favor a transverse incision regardless of size or location of the fibroids. If a Pfannenstiel incision is first created, another option is to convert to a Cherney incision, rather than Maylard, in order to preserve the vascular supply to the anterior rectus sheath.

The surgical approach typically begins with a transverse abdominal incision (Pfannenstiel or Maylard) unless exam under anesthesia reveals pathology more safely approached through a midline incision. Patients with deep posterior tumors, especially if large, may pose a formidable obstacle for the surgeon as these are not only difficult to visualize (bony pelvic inlet, sigmoid/colon/rectum), but even if successfully enucleated, may be exceedingly difficult to repair unless a lengthy fascial incision is made. Patient habitus, such as those with a longer distance between anterior superior iliac spines and shorter distance from the pubic symphysis to umbilicus may favor a transverse incision regardless of size or location of the fibroids. If a Pfannenstiel incision is first created, another option is to convert to a Cherney incision, rather than Maylard, in order to preserve the vascular supply to the anterior rectus sheath.

The surgical approach typically begins with a transverse abdominal incision (Pfannenstiel or Maylard) unless exam under anesthesia reveals pathology more safely approached through a midline incision. Patients with deep posterior tumors, especially if large, may pose a formidable obstacle for the surgeon as these are not only difficult to visualize (bony pelvic inlet, sigmoid/colon/rectum), but even if successfully enucleated, may be exceedingly difficult to repair unless a lengthy fascial incision is made. Patient habitus, such as those with a longer distance between anterior superior iliac spines and shorter distance from the pubic symphysis to umbilicus may favor a transverse incision regardless of size or location of the fibroids. If a Pfannenstiel incision is first created, another option is to convert to a Cherney incision, rather than Maylard, in order to preserve the vascular supply to the anterior rectus sheath.Once the peritoneal cavity is entered, per reproductive surgery principles (see Chapter 22), the surgeon should wash his or her gloves with a moistened laparotomy sponge to remove any potential remaining irritants. The uterus, cul-de-sac, and adnexa are then gently palpated to obtain a clear picture of the uterine anatomy, complemented by reference to preoperative imaging results. This will allow the surgeon to plan the surgical approach. It may be useful to first deliver the myomatous uterus upward through the incision, not only for surgical ease but also to fully identify all potential tumors for resection. However, this may expose the uterus to a greater risk for peritoneal desiccation. Minimal use of laparotomy sponges to retract or grasp is recommended, as these are quite abrasive.

Tactically, two issues should be considered. First, it is best to allow a readily accessible medium to a large-sized fibroid to remain until the end of the procedure, as these fibroids can be grasped to facilitate manipulation of the uterus. Alternatively, it may be necessary to remove those fibroids that are easiest to access initially, permitting access to myomas that are in more difficult-to-reach locations.

A technique we have found useful to facilitate the identification of the endometrial layer at myomectomy, particularly when the myomas are suspected of abutting the uterine cavity or there is a possibility that the endometrial cavity will be entered, is to instill indigo carmine or methylene blue into the cavity. This will stain the endometrium a bluish tint and will make it easier to identify entry into the endometrial cavity and facilitates the identification of the incised endometrial edges for repair. Staining with dilute methylene blue (1%) lasts longer than with indigo carmine. Dye instillation can be performed transvaginally, through the cervix, or via an angiocath placed through the uterine fundus, although this may be difficult when the uterine cavity is significantly distorted by the myomas.

Following, we initially describe the resection of an uncomplicated fundal or anterior myoma, followed by uterine reconstruction. Subsequently, we address the removal of myomas in more difficult locations (e.g., posterior, cervical, pedunculated, cornual, interligamentous, intracavitary, and multiple adjacent myomas).

2. Myomectomy of a fundal/anterior myoma: Once the uterus and tumors have been examined, and the approach established, the first incision is then planned. This incision should generally overlie the most pronounced area of the myoma, be directed transversely if well removed from the interstitial/cornual region of the uterus, as close to the midline as possible. Transverse incisions should not be used when operating close to the

uterine cornua, in order to prevent extension into the intramural portion of the tubes.

uterine cornua, in order to prevent extension into the intramural portion of the tubes.

The incision size should be kept to the minimum necessary, and should not be made to accommodate the entire girth of the myoma, as morcellation of the tumor should be used if necessary. A vasoactive agent (we suggest vasopressin [Pitressin®] 20 U diluted in 50 cc of normal saline) is injected around the area of the planned incision, both superficially and deep into the myometrium. The anesthesiologist should be informed of the injection before it is administered. Some surgeons use a rubber tourniquet placed through the broad ligament compressing the uterine vasculature at the level of the internal os, although this surgeon views that approach as excessively risky.

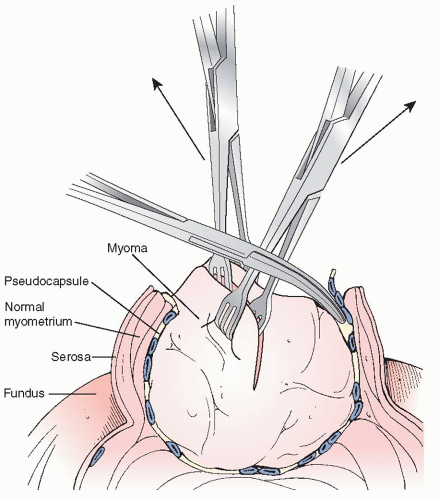

A scalpel is used to incise the serosa and myometrium down to and into the fibroid itself. It is important that the surgeon understand that the incision must be carried deep into the myoma itself, preferably at least halfway the full width of the myoma. This technique allows the normal myometrium to retract from the less elastic fibroid (Figure 28.2), and allows the surgeon to better identify the true plane between the fibroid and normal (yet compressed) myometrium for atraumatic and relative bloodless enucleation. Alternatively, if the incision is not carried into the fibroid, then there is a high likelihood that the dissection will be started at the myometrial pseudocapsule, with all its flattened vessels, resulting in significant bleeding and damage to normal myometrium

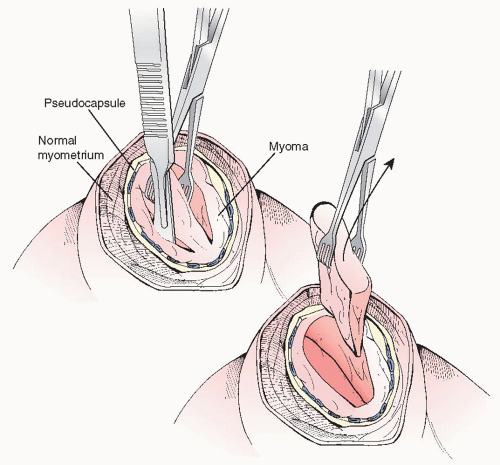

Using a towel clamp or a Lahey traction forceps for external traction, a curved Kelly or Pean clamp can be used to dissect the fibroid in a multidirectional approach, following the avascular planes between the myoma and the myometrial pseudocapsule (Figure 28.2). In a stepwise fashion, most

fibroids may be removed intact. However, if myomas are large, serial wedge-type morcellation with a scalpel should be considered (Figure 28.3). There is no need to take out fibroids “intact,’ and in fact, the serosal incision should not be made as large as the myoma; it should be made just sufficient to allow for dissection of the myoma from its bed and to permit wedge morcellation. We do not recommend the use of Allis clamps to grasp the serosa or myometrium for countertraction purposes as these only create more injured surfaces and potential nidus for adhesion formation.

fibroids may be removed intact. However, if myomas are large, serial wedge-type morcellation with a scalpel should be considered (Figure 28.3). There is no need to take out fibroids “intact,’ and in fact, the serosal incision should not be made as large as the myoma; it should be made just sufficient to allow for dissection of the myoma from its bed and to permit wedge morcellation. We do not recommend the use of Allis clamps to grasp the serosa or myometrium for countertraction purposes as these only create more injured surfaces and potential nidus for adhesion formation.

The blood supply to the fibroid is peripheral and circumferential, rather than central (Figure 28.1). Myomas flatten and stretch the arcuate vessels of the uterus which run in a transverse pattern. If dissection through planes just exterior to the fibroid takes place, significant bleeding and oozing can occur. Accordingly, most incisions should be made in a transverse fashion to reduce bleeding and make for an easier closure. This is not always possible, and proximity to the interstitial portion of the oviduct and vascular supply should take precedence. Electrosurgery and electrocoagulation can be used in the deeper layers of the myometrium to achieve hemostasis of transected perimyomatous vessels. On occasion, a particularly large vessel may have to be isolated and tied off.