The Initial Approach: Dangers, Responsive, Send for Help (DRS)

In the external environment, it is essential that the rescuer does not become a second victim, and that the child is removed from continuing danger as quickly as possible. These considerations should precede the initial airway assessment. Within a health care setting the likelihood of risk is decreased and help should be summoned as soon as the victim is found to be unresponsive. The steps are summarised in Figure 4.2.

When more than one rescuer is present, one starts BLS while another activates the emergency medical services (EMS) system and then returns to assist in the BLS effort. If there is only one rescuer and no help has arrived after 1 minute of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), then the rescuer must activate the EMS system him- or herself. In the case of a baby or small child the rescuer will probably be able to take the victim with him or her to a telephone whilst attempting to continue CPR on the way.

Phone First

In a few instances the sequence in the above paragraph is reversed. As previously described, in children, respiratory and circulatory causes of cardiac arrest predominate, and immediate respiratory and circulatory support as provided by the breaths and chest compressions of BLS can be life saving. However, there are circumstances in which early defibrillation may be life saving, i.e. cardiac arrests caused by arrhythmia. On these occasions, where there is more than one rescuer, one may start BLS and another summon the EMS as above. But if there is a lone rescuer then he or she should activate the EMS system first on witnessing the collapse and then start BLS afterwards.

Clinical indications for EMS activation before BLS by a lone rescuer include:

- Witnessed sudden collapse with no apparent preceding morbidity.

- Witnessed sudden collapse in a child with a known cardiac condition and in the absence of a known or suspected respiratory or circulatory cause of arrest.

The increasingly wide availability of public access defibrillation programmes with automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) may result in a better outcome for this small group (see p. 29).

Responsive?

The initial simple assessment of responsiveness consists of asking the child ‘Are you alright?’ and gently applying a stimulus such as holding the head and shaking the arm. This will avoid exacerbating a possible neck injury whilst still waking a sleeping child. Infants and very small children who cannot talk yet, and older children who are very scared, are unlikely to reply meaningfully, but may make some sound or open their eyes to the rescuer’s voice or touch.

Airway (A)

An obstructed airway may be the primary problem, and correction of the obstruction can result in recovery without further intervention. If a child is not breathing it may be because the airway has been blocked by the tongue falling back and obstructing the pharynx. An attempt to open the airway should be made using the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre. The rescuer places the hand nearest to the child’s head on the forehead and applies pressure to tilt the head back gently. The desirable degrees of tilt are neutral in the infant and ‘sniffing’ in the child. These are shown in Figures 4.3 and 4.4. The fingers of the other hand should then be placed under the chin and the chin should be lifted upwards. Care should be taken not to injure the soft tissue by gripping too hard. As this action can close the child’s mouth, it may be necessary to use the thumb of the same hand to part the lips slightly. In the infant, the head is placed in the neutral position; in the child, the head should be in the ‘sniffing’ position.

If a child is having difficulty breathing, but is conscious, then transport to hospital should be arranged as quickly as possible. A child will often find the best position to maintain his or her own airway, and should not be forced to adopt a position that may be less comfortable. Attempts to improve a partially maintained airway in a conscious child in an environment where immediate advanced support is not available can be dangerous, because total obstruction may occur.

The patency of the airway should then be assessed. This is done by:

LOOKing for chest and/or abdominal movement

LISTENing for breath sounds

FEELing for breath

and is best achieved by the rescuer placing his or her face above the child’s, with the ear over the nose, the cheek over the mouth and the eyes looking along the line of the chest for up to 10 seconds.

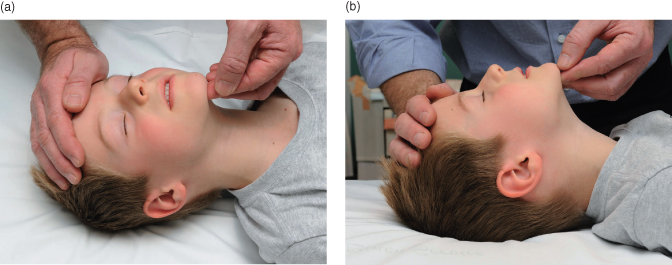

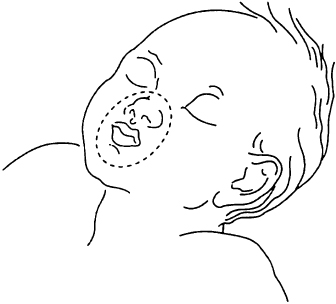

If the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre is not possible or is contraindicated because of suspected neck injury, then the jaw thrust manoeuvre can be performed. This is achieved by placing two or three fingers under the angle of the mandible bilaterally and lifting the jaw upwards. This technique may be easier if the rescuer’s elbows are resting on the same surface as the child is lying on. A small degree of head tilt may also be applied if there is no concern about neck injury. This is shown in Figure 4.5.

It should be noted that, if there is a history of trauma, then the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre may exacerbate cervical spine injury. In general, the safest airway intervention in these circumstances is the jaw thrust without head tilt. However, on rare occasions, it may not be possible to control the airway with a jaw thrust alone in trauma. In these circumstances, an open airway takes priority over cervical spine risk and a gradually increased degree of head tilt may be tried. Cervical spine control should be achieved by a second rescuer maintaining in-line cervical stabilisation throughout.

The blind finger sweep technique should not be used in children. The child’s soft palate is easily damaged, and bleeding from within the mouth can worsen the situation. Furthermore, foreign bodies may be forced further down the airway; they can become lodged below the vocal cords and be even more difficult to remove. In the child with a tracheostomy, additional procedures are necessary (see Section 20.7).

Breathing (B)

If normal breathing starts after the airway is open, turn the child onto his or her side in the recovery position (see later), maintaining the open airway. Send or go for help and continue to monitor the child for normal breathing. If the airway-opening techniques described above do not result in the resumption of adequate breathing within 10 seconds, exhaled air resuscitation should be commenced. The rescuer should distinguish between adequate breathing and ineffective, gasping or obstructed breathing. If in doubt, attempt rescue breathing.

Two resuscitation breaths should be given

While the airway is kept open as described above, the rescuer breathes in and seals his or her mouth around the victim’s mouth (for a child), or mouth and nose (for an infant, as shown in Figure 4.6). If the mouth alone is used then the nose should be pinched closed using the thumb and index fingers of the hand that is maintaining the head tilt. Slow exhalation (1–1.5 seconds) by the rescuer should make the victim’s chest rise as much as normal – too vigorous a breath will cause gastric inflation and increase the chance of regurgitation of stomach contents into the lungs. The rescuer should take a breath between resuscitation breaths to maximise oxygenation of the victim.

If the rescuer is unable to cover the mouth and nose in an infant, he or she may attempt to seal only the infant’s nose or mouth with his or her mouth and should close the infant’s lips or pinch the nose to prevent air escape.

- The chest should be seen to rise

- Inflation pressure may be higher because the airway is small

- Slow breaths at the lowest pressure reduce gastric distension

- Firm, gentle pressure on the cricoid cartilage may reduce gastric insufflation

If the chest does not rise then the airway is not clear. The usual cause is failure to apply correctly the airway-opening techniques discussed above. Thus, the first thing to do is to readjust the head tilt/chin lift position, and try again. If this does not work a jaw thrust should be tried. It is quite possible for a single rescuer to open the airway using this technique and perform exhaled air resuscitation; however, if two rescuers are present one should maintain the airway whilst the other breathes for the child. Two breaths are given. While performing resuscitation breaths note any gag or cough response to your action. These responses, or their absence, will form part of your assessment of ‘signs of life’ described below.

Failure of both head tilt/chin lift and jaw thrust should lead to the suspicion that a foreign body is causing the obstruction, and appropriate action should be taken (see Section 4.4).

Circulation (C)

Once the resuscitation breaths have been given as above, attention should be turned to the circulation.

Assessment

Failure of the circulation is recognised by the absence of signs of circulation (‘signs of life’), i.e. no normal breaths or cough in response to resuscitation breaths and no spontaneous movement. In addition, an absent central pulse (for up to 10 seconds) or the presence of a pulse at an insufficient rate may be detected.

Even experienced health professionals can find it difficult to be certain that the pulse is absent within 10 seconds. Therefore, the absence of ‘signs of life’ is the primary indication to start chest compressions. Signs of life include: movement, coughing or normal breathing (not agonal gasps – these are irregular, infrequent breaths).

In children, the carotid artery in the neck or the femoral artery in the groin can be palpated. In infants, the neck is generally short and fat and the carotid artery may be difficult to identify. Therefore the brachial artery in the medial aspect of the antecubital fossa (Figure 4.7) or the femoral artery in the groin can be felt.

Figure 4.7 Feeling for the brachial pulse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree