- The name of the child

- The date and time that the film was taken

- The orientation (side marker position)

The ABCD approach to radiographic interpretation is shown in the following box:

23.2 CERVICAL SPINE RADIOGRAPH

Cervical spine immobilisation should take place before any radiographs are performed. The standard film is a lateral radiograph, which may be supplemented by anteroposterior (AP) radiographs (lower cervical spine and odontoid peg views) when appropriate. If the child has an adequately fitted cervical collar for immobilisation it is very difficult to get good-quality AP views, including the odontoid peg. Sandbags should not be used for immobilisation as they may obscure bony landmarks.

Bony injury in itself is not the prime concern in spinal injury. The main risk is actual or potential injury to the cord. Any unstable fracture, if inadequately immobilised, may lead to progressive cord damage.

A lateral cervical spine film is often requested to ‘clear’ the cervical spine, but a normal film may be falsely reassuring. The plain film only shows the position of the bones at the time the film was taken, and gives no idea of the magnitude of the flexion and extension forces applied to the spine at the time of injury. The cord may be injured even in a child without any apparent radiographic abnormality.

Most paediatric cervical spine injuries in children under 8 years of age occur through the discs and ligaments at the craniovertebral junction (C1, C2 and C3). The relatively large mass of the head, moving on a flexible neck with poorly supportive muscles, leads to injury in the higher cervical vertebrae. Children over 8 years of age have an injury profile similar to adults (predominantly C5, C6 and C7).

Children develop three patterns of spinal injury:

The last of these, SCIWORA, is said to have occurred when radiographic films are totally normal in the presence of significant cord injury. If the film is normal in a conscious child with clinical symptoms (such as pain, loss of function or paraesthesia in a limb) then neck protection measures should be continued. In an unconscious child at high risk, a cord injury cannot be excluded until the patient is awake and has been assessed clinically, even in the presence of a normal cervical spine film. Adequate spinal precautions should be continued until the child is well enough to be assessed clinically, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been carried out.

The most common site of a ‘missed’ spinal injury is where a flexible part of the spine meets the fixed part. In the neck these are the cervicocranial junction and the cervicothoracic junction.

Adequacy

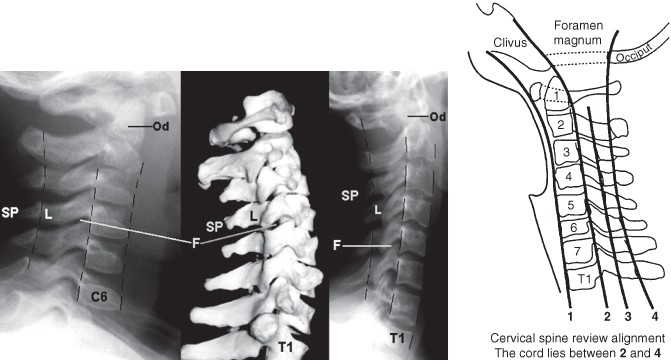

The whole spine should be viewed from the lower clivus down to the upper body of the T1 vertebra. If the C7/T1 junction is not seen initially then gentle traction should be applied by pulling the arms down, holding them above the elbow joint. If the child is conscious they should be asked to relax their shoulders as traction is applied. If the child is on a spinal board then this must be stabilised by an assistant.

Alignment

The four lines, three of which are shown in Figure 23.1, should be reviewed. These are:

Figure 23.1 Lateral cervical spine scans showing the anatomy and three of the four review lines and disc spaces (facet joints and line not shown). F, facet joint; L, lamina; Od, odontoid; SP, spinous process spaces.

The continuity of these lines should be maintained, no matter what the degree of flexion or extension seen on the neck film. There should be no ‘steps’ or angulation.

The spinal cord lies in the canal between the posterior vertebral (line 2) and the spinolaminar (line 4) lines. The former should line up with the clivus and the latter with the back of the foramen magnum.

Bones

The outline of each vertebra should be reviewed in turn. Fracture lines going through the cortex, vertebral bodies, laminae or spinous processes should be sought.

The spaces between the facet joints and the gaps between adjacent spinous processes should be similar (Figure 23.1).

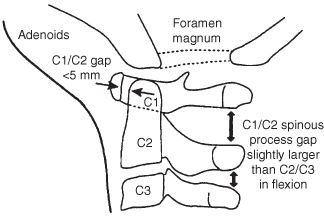

The joint between the odontoid peg and the anterior arch of the atlas should be less than 5 mm in a child (Figure 23.2).

The gap between the posterior arch of C1 and the spinous process of C2 may be slightly larger than the gaps at the other levels in flexion. The base of the odontoid peg may not be completely fused onto the body of the axis (C2) in a small child, but the orientation of the odontoid peg should always be perpendicular to the body of C2.

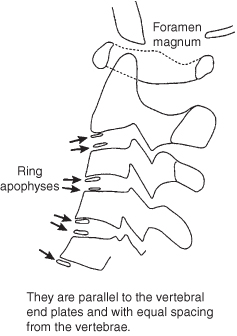

In adolescence, ring apophyses are seen related to the vertebral bodies, as shown in Figure 23.3. These are sometimes a site for fracture separation from the vertebral body. The appearances of the apophyses at each level should be compared with the vertebra above and below.

Cartilage and Soft Tissues

Abnormal widening of the prevertebral soft tissues may indicate a haematoma due to cervical spine injury. There may, however, be a significant spinal injury with normal soft tissues – thus the absence of soft tissue swelling does not exclude major bony or ligamentous injury. When a child is intubated, it is difficult to assess prevertebral soft tissue swelling. Small children have large adenoids, which are seen as well-demarcated soft tissue swelling at the base of the clivus.

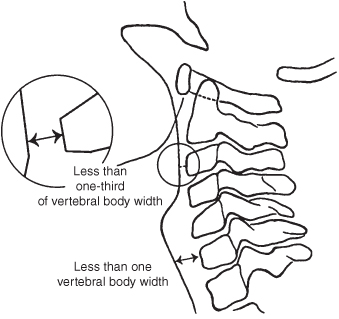

Acceptable soft tissue thicknesses are (Figure 23.4, overleaf):

- Above the larynx: less than one-third of the vertebral body width.

- Below the larynx: not more than one vertebral body width.

Figure 23.4 Lateral cervical spine: soft tissues (see also line drawing in Figure 23.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree